Elizabeth H. Blackburn

University of California, San Francisco

Carol W. Greider

Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine

Jack W. Szostak

Harvard Medical School

For the prediction and discovery of telomerase, a remarkable RNA-containing enzyme that synthesizes the ends of chromosomes, protecting them and maintaining the integrity of the genome.

The 2006 Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research honors three scientists who predicted and discovered telomerase, an enzyme that replenishes the ends of chromosomes. In so doing, they unearthed a biochemical reaction that guards cells against chromosome loss and identified the molecular machinery that performs this feat. The work resolved perplexing observations about chromosome termini and explained how cells copy their DNA extremities.

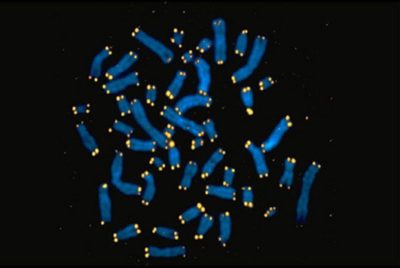

In the 1930s, scientists surmised that protective caps — telomeres — ensure the propagation of chromosomes during cell division and prevent them from inappropriately melding with one another. The physical nature of these structures — and how they are constructed — eluded researchers until Elizabeth Blackburn, Carol Greider, and Jack Szostak performed their groundbreaking investigations in the late 1970s and 1980s. Blackburn showed that simple repeated DNA sequences comprise chromosome ends and, with Szostak, established that these repeats stabilize chromosomes inside cells. Szostak and Blackburn predicted the existence of an enzyme that would add the sequences to chromosome termini.

Award presentation by Joseph Goldstein

The discovery of telomerase centers around four principal characters — a single-cell protozoan that swims in freshwater ponds, propelled by hairlike projections called cilia; a Tasmanian-born devourer of Amanda Cross mystery novels; a triathlete and competitive vaulter who performs handstands on the back of a speeding horse; and a 53-year-old virgin prizewinner.

The discovery of telomerase centers around four principal characters — a single-cell protozoan that swims in freshwater ponds, propelled by hairlike projections called cilia; a Tasmanian-born devourer of Amanda Cross mystery novels; a triathlete and competitive vaulter who performs handstands on the back of a speeding horse; and a 53-year-old virgin prizewinner.

So what is telomerase and why is it Lasker Prize-worthy? As you all know, life depends on the genetic instructions carried in the DNA of the genome.

Acceptance remarks

Acceptance remarks, 2006 Lasker Awards Ceremony

I feel greatly privileged to be recognized by a Lasker Award, and I want to convey my thanks and appreciation to the Selection Jury and to the Lasker Foundation for this very great honor.

Standing here today and thinking about the journey that has brought me here, I also feel a certain poignancy, because my mother, who is no longer alive, would have been particularly proud, and would have loved to be here. I remember the delight with which she would often tell me of how, when I was six years old, the teacher of a little rural grade school in the West of England, which I had been attending while my family was visiting from Australia, had said to her of me: “She will go far.”

This must have been gratifying indeed to hear for a parent who had had to live with my spine-chilling habit, in Australia, of picking up dangerous animals — poisonous jellyfish from the beach and stinging ants from twigs — and singing to them, behavior I thought perfectly natural because I loved animals. I was lucky to be given the circumstances that could transmute that childhood enthusiasm into a lifelong passion for doing science. I would wish everyone such good fortune.

I feel proud in turn of being part of a great tradition of biomedical research. I would like to see it stay strong and vibrant. To foster the best research and develop the best science policies, I want to say a couple of things that I believe we need to remember.

First, about research itself: It is important never to forget that science is as creative an endeavor as the humanities. Along with its more familiar aspects — like the necessary rigorous standards of proof — doing science is also letting the imagination be open to new ideas and lateral leaps that might at first seem outlandish. That means — as was true for our research that led to telomerase — having the freedom to do novel experiments at times, sometimes with obscure creatures. Joe Gall helped me appreciate this when I was a postdoctoral fellow with him. Because biology sometimes reveals its general principles through what may seem at first to be arcane and bizarre. All living things work fundamentally the same way when you get down to their molecules and cells; it is the extent and setting in which the various molecular processes are played out that differ from pond scum to humans, not their innermost workings.

The other thing I want to say is we certainly do not know where all our advances in understanding biology are headed: For a healthy science policy that serves society best, an environment of openness to available scientific evidence and freely shared and expounded ideas is crucial. We must surely keep alive a commitment to this. I feel very lucky to have been able to do science here in my adoptive country, the United States. But to realize the full promise of biological research we mustn’t fear new biological science, as sometimes seems to happen.

A scientific heroine of mine, Marie Curie, the discoverer of radium, said it well: “Nothing in life is to be feared. It is only to be understood.” Thank you.

Acceptance remarks, 2006 Lasker Awards Ceremony

It is indeed an honor to receive the Lasker Award. Working on telomeres and telomerase over the past 20 years has taken me on a ride though many disciplines in biology, from biochemistry to cellular senescence and aging, to recombination, the DNA damage response, and cancer. Today, we are delving into human genetics and stem cell biology. I have been very fortunate to have the opportunity to participate in these different research communities, to make new friends and collaborators, and to be exposed to new ideas and questions.

The most important lesson I have learned on this ride is that science is inherently a community activity. Ideas are created by thinking about your own experiments in the context of established knowledge and also thinking hard about other people’s experiments. When new ideas emerge they are discussed, critiqued, and modified. Often this process goes on unacknowledged. It is the exchange of ideas with the members of my laboratory that I find most exciting. Good ideas for the next most interesting experiments can come from many places; in my lab they almost always come from the students and postdocs who work with me. This lesson — that science is a community activity — is one of the most rewarding that I have learned.

I am grateful for the opportunity this award presents me to give back to the scientific community, by advocating the importance of fundamental, curiosity-driven research. The true value of high-profile awards is that it gives one the chance to explain publicly the nature of the scientific process and the importance of basic, non-applied work. Telomerase beautifully illustrates that you never know where medically relevant discoveries might come from. From studying Tetrahymena and yeast, we learn about cancer and stem cells. It has been a thrilling 20-year ride, I cannot wait to see where telomeres and telomerase will lead us in the next 20 years.

Acceptance remarks, 2006 Lasker Awards Ceremony

I would like to express my gratitude to the Lasker Foundation, and to Joe Goldstein and the other members of the jury, for this Award.

I am particularly happy to be recognized for my work on telomeres for several reasons — for one, the work was done so long ago that it has sometimes seemed to me to be almost forgotten. I am grateful to the jury for digging so deeply into the history of this field! Since then, I’ve worked in several rather different areas, but the experiment that Liz and I collaborated on, putting Tetrahymena telomeres into yeast, has always been one of my favorites.

I still remember discussing the idea with Liz at a Gordon Conference, and then the excitement when it actually worked and all of a sudden the door was opened to a whole series of new possibilities. To me, this experiment illustrates perfectly the value of talking to people who work in very different fields, the value of collaboration, and the value of, every now and then, putting a little money and effort into high risk, high payoff experiments.

It is a particular delight to be sharing this Award with Liz Blackburn, my collaborator from so long ago, and with Carol Greider, Liz’s former student who has done so much to develop the biochemistry of telomerase. When we did our work 20, 25 years ago, none of us could have anticipated the significance of the molecular biology of telomeres to aging and cancer. Our work was purely curiosity-driven basic science, and the biomedical significance emerged only later. I thank the Lasker Foundation once again for this recognition of our early work, and for their continued public support of basic research.