John Gurdon

Cambridge University

Shinya Yamanaka

Kyoto University

For discoveries concerning nuclear reprogramming, the process that instructs specialized adult cells to form early stem cells — creating the potential to become any type of mature cell for experimental or therapeutic purposes.

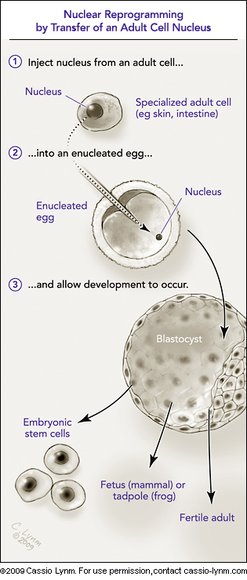

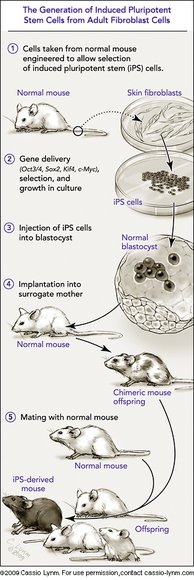

The 2009 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award honors two scientists for their discoveries concerning nuclear reprogramming. This process instructs fully specialized adult cells how to turn into stem cells that can guide the formation of any tissue type. Nuclear reprogramming thus provides the means to create invaluable materials for experimental or therapeutic purposes. In the late 1950s, John Gurdon (Cambridge University) transferred nuclei from adult cells into eggs and showed that the resulting cells took on embryonic characteristics. This advance established that cells retain all of their genes as they specialize and that fully developed cells can be re-set to an embryonic state — controversial discoveries at the time. Decades later, Shinya Yamanaka (Kyoto University) unlocked a new realm of practical possibilities for nuclear reprogramming when he made adult cells behave like embryonic cells by adding only a few factors. This revelation has offered scientists novel ways to harness and study the powers of embryonic development.

Although much work remains to determine whether nuclear reprogramming techniques will prove safe and effective enough for clinical use, Gurdon’s and Yamanaka’s discoveries have opened potential avenues toward personalized cell-replacement therapies. Such treatments might offer a means to restore malfunctioning or worn out tissues without subjecting a patient to the risks of immune rejection. Reprogrammed cells also afford novel approaches toward understanding currently inscrutable diseases and for screening drugs to thwart these conditions. Moreover, because scientists can create reprogrammed cells from adult tissue, the technologies come without the controversy that accompanies methods based on embryonic stem cells.

Award presentation by Harold Varmus

Every person in this room, no exceptions, originated from a single cell, a fertilized egg. How did that single cell generate the hundreds of different types of cells that populate our complex bodies?

Every person in this room, no exceptions, originated from a single cell, a fertilized egg. How did that single cell generate the hundreds of different types of cells that populate our complex bodies?

Science now offers some answers. A fertilized egg contains a program for development, encoded in DNA. The same instructions are found in nearly all adult cells. Mature cell types differ from each other because different parts of the script, different genes, are read-out.

Consider another facet of this situation. If adult cells retain the instructions for development, why can’t any cell, even a highly specialized one, be reprogrammed — so that it behaves like an immature cell, prepared to produce many different types of cells, even an entire organism?

The two basic scientists we honor today have shown that this remarkable thing, reprogramming, can indeed occur. They have accomplished it at different times in the history of biology, in different ways, and with different consequences.

Acceptance remarks

Acceptance remarks, 2009 Lasker Awards Ceremony

Anyone who is accorded a Lasker Award in Basic Medical Science is immensely grateful, and I more than others for the following reason. This is that the primary work for which recognition is kindly made is for experiments done over 50 years ago. This testifies to the meticulous care of the highly distinguished members of the jury, a characteristic for which they are famous. To look back at the work done in 1958 is exceptional by any standards, and I can only say how grateful I am.

The same point merits a little further comment. At that time in the late 1950s and early 1960s, I don’t think anyone could have foreseen the relevance of nuclear transplantation to current ideas of cell replacement. The original aim of these experiments was to determine whether or not the genome remained constant in all cell types. The possibility of deriving one cell type from another clearly existed. But two key advances were necessary for this to become a reality in humans. One was that embryonic stem cells needed to be able to proliferate indefinitely without the usual accompanying process of progressive differentiation that takes place in normal development. The major discovery of embryonic stem cells by Martin Evans in 1981 has indeed been recognized by a Lasker and other awards. The other key advance is that of Shinya Yamanaka with his discovery of iPS cells, obviating the need to obtain human eggs. It is a special pleasure to find myself honored at the same time as Shinya Yamanaka.

Looking further ahead in my own direction of work, I like to think that it will be eventually useful to identify the molecules and mechanisms by which eggs can efficiently reprogram sperm after fertilization and somatic nuclei after transplantation to eggs. These natural molecules could be put to use in facilitating the derivation of embryonic stem cells from adult tissues in humans. Our recent work all indicates that the molecules and mechanisms of reprogramming by eggs are quite different from those that take place by the iPS route.

The history of nuclear transfer and its potential relevance to cell replacement exemplifies the principle, so often seen in many previous Lasker Awards. This is that a question and answer in basic science very commonly turn out, in a way not at all predicted at the time, to have a potential relevance and usefulness for human health.

I am enormously grateful for this award.

Acceptance remarks, 2009 Lasker Awards Ceremony

It is a tremendous honor to receive the 2009 Lasker Award, especially at the same time along with the illustrious Sir John Gurdon, the father of nuclear reprogramming. I would like to sincerely express my utmost gratitude to both the Lasker Foundation and to the Selection Committee.

Several years ago, I contributed an essay to a Japanese newspaper. At that time I wrote, “Science is a process which allows us to remove multiple layers of veils which are covering the truth. When scientists remove one veil, they often end up finding another new veil. However, when a lucky scientist removes a certain veil, then he is sometimes able to suddenly find the truth. This lucky scientist then publishes a paper in a prestigious journal and thereafter becomes widely acclaimed. However, we should always remember that the uncovering of each veil is equally important. It is therefore not fair if only such lucky scientists are praised.”

Upon humbly accepting the Lasker Award, I would like to stress that the key point to my previous essay still remains valid today. The generation of iPS cells is based on the findings of numerous scientists in the field of nuclear reprogramming, which was initiated by Sir John Gurdon, as well as countless researchers in many other related fields. Since our initial report on iPS cells, many scientists have been tirelessly working to find new breakthroughs and are now advancing this technology at a surprising speed. I therefore humbly accept today’s award on behalf of the many scientists who have contributed to this technology, and for my colleagues, fellows, and students, who as a team ultimately made it possible for us to succeed in making iPS cells.

Science is full of surprises. In my very first experiment as a graduate student in pharmacology, a drug, which I had predicted would increase blood pressure, turned out to cause profound hypotension. When I was a postdoctoral fellow, a gene, which we had expected to potentially use in gene therapy, ended up causing horrible cancers. Science is unpredictable. The iPS cell technology is still in its infancy. Its potential use and applications in medicine are enormous, but there are also many challenges which need to be overcome before it can be successfully applied to the discovery of new drugs and regenerative medicine. It is hard to predict what will happen five years from now. Both I and all of my colleagues will continue to do our best to promote the medical and pharmaceutical applications of iPS cell technology.

Finally, I would like to wholeheartedly thank my colleagues at Gladstone and Kyoto, my friends, and my family for their continuous support, without whom I could never have had the good fortune to be with you here today.

Interview with John Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka

Video Credit: Susan Hadary