In the late 1950s, the WHO embarked on an ambitious project to eradicate malaria. After limited success, the disease rebounded in many places, due in part to the emergence of parasites that resisted drugs such as chloroquine that had previously held the malady at bay. At the beginning of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the Chinese government launched a secret military project that aimed to devise a remedy for the deadly scourge. China was particularly motivated to prevail over malaria not only because it was a significant problem at home, but also because the Vietnamese government had asked for help. It was at war and the affliction was devastating its civilian and military populations.

The covert operation, named Project 523 for the day it was announced — May 23, 1967 — set out to battle chloroquine-resistant malaria. The clandestine nature of the enterprise and the political climate created a situation in which few scientific papers concerning the project were published for many years, the earliest ones were not accessible to the international community, and many details about the endeavor are still shrouded in mystery. In early 1969, Tu was appointed head of the Project 523 research group at her institute, where practitioners of traditional medicine worked side by side with modern chemists, pharmacologists, and other scientists. In keeping with Mao Zedong’s urgings to “explore and further improve” the “great treasure house” of traditional Chinese medicine, Tu combed ancient texts and folk remedies for possible leads. She collected 2000 candidate recipes, which she then winnowed. By 1971, her team had made 380 extracts from 200 herbs. The researchers then assessed whether these substances could clear Plasmodia from the bloodstream of mice infected with the parasite.

One of the extracts looked particularly promising: Material from Qinghao (Artemisia annua L., or sweet wormwood) dramatically inhibited parasite growth in the animals. Such hopeful results, however, were not reproducible, so Tu dove back into the literature and scoured it for possible explanations.

The first known medical description of Qinghao lies in a 2000-year-old document called “52 Prescriptions” (168 BCE) that had been unearthed from a Mawangdui Han Dynasty tomb. It details the herb’s use for soothing hemorrhoids. Later texts also mention the plant’s curative powers. Tu discovered a passage in the Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies (340 CE) by Ge Hong that referenced Qinghao’s malaria-healing capacity. It said “Take a handful of Qinghao, soak in two liters of water, strain the liquid, and drink.” She realized that the standard procedure of boiling and high-temperature extraction could destroy the active ingredient.

With this idea in mind, Tu redesigned the extraction process, performing it at low temperatures with ether as the solvent. She also removed a harmful acidic portion of the extract that did not contribute to antimalarial activity, tracked the material to the leaves rather than other parts of the plant, and figured out when to harvest the herb to maximize yields. These innovations boosted potency and slashed toxicity. At a March 1972 meeting of the Project 523 group’s key participants, she reported that the neutral plant extract — number 191 — obliterated Plasmodia in the blood of mice and monkeys.

From branch to bedside

Later that year, Tu and her team tested the substance on 21 people with malaria in the Hainan Province, an island off the southern coast of China. About half the patients were infected with Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest of the microbial miscreants, and about half were infected with Plasmodium vivax, the most common cause of a disease variant that is characterized by recurring fevers. In both groups, fever disappeared rapidly, as did blood-borne parasites.

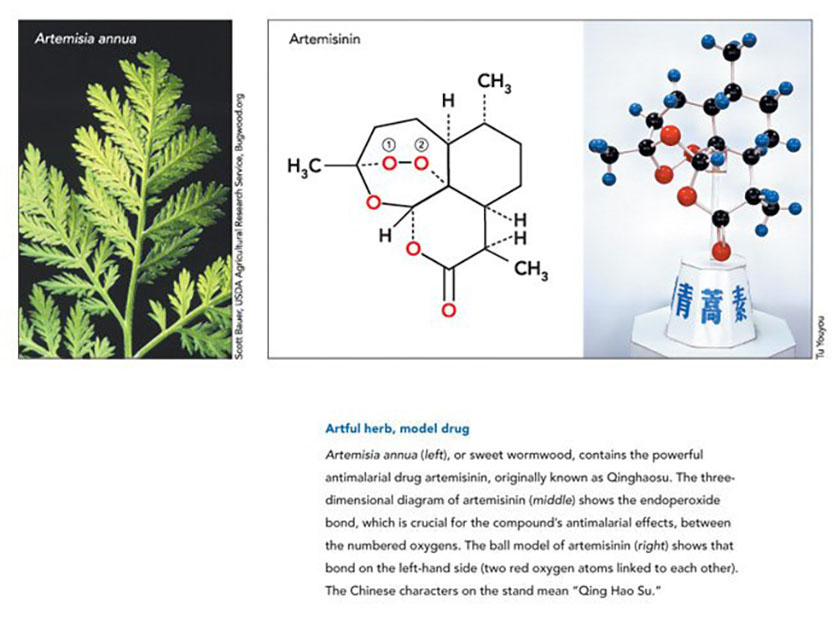

In the meantime, Tu started to home in on the active ingredient, using chromatography to separate the extract’s components. On November 8, 1972, she and her colleagues obtained the pure substance. They named it Qinghaosu (literally, the principle of Qinghao) and it is now commonly called artemisinin in the West. Tu and her colleagues subsequently determined that it had an unusual structure. It proved to be a sesquiterpene lactone with a peroxide group, a completely different kind of compound than any known antimalarial drug. Later studies would show that the peroxide portion is essential for its lethal effects on the parasite.

Subsequent clinical trials on 529 malaria cases confirmed that the crystal they had isolated delivers the antimalarial blow. Many scientists from other institutes then joined efforts to improve the extraction procedures and conduct clinical trials. The first English-language report about artemisinin was in December 1979; as was customary at the time in China, the authors were anonymous. By that point, the China-wide Qinghaosu research group had given the substance to more than 2000 patients, some of whom had chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria infections. In addition, the drug cured 131 of 141 individuals with cerebral malaria, a particularly severe form of the disease. Comparative studies on a small number of cases suggested that the drug acted more quickly than chloroquine did. The investigators reported no harmful side effects.

The paper drew international attention. In October 1981, the scientific working group on the chemotherapy of malaria, sponsored by the WHO, the World Bank, and United Nations Development Business, invited Tu to present her findings at its fourth meeting. Her talk evoked an enthusiastic response. She told the audience not only about artemisinin, but also about some of its chemical derivatives. In 1973, as part of her structural studies, Tu had modified artemisinin to generate a compound called dihydroartemisinin. She later found that it delivers ten times more punch than artemisinin and that it reduces risk of disease recurrence. This compound provided the basis for other artemisinin-derived drugs. Starting in the mid 1970s, Guoqiao Li (Guangzhou College of Traditional Chinese Medicine) performed clinical trials with artemisinin and these substances. They all delivered more therapeutic clout than did standard drugs such as chloroquine and quinine. The derivatives tend to hold up better than the parent compound in the body, and they form the foundation of today’s therapies.

In 1980, Keith Arnold (Roche Far East Research Foundation, Hong Kong) joined Li’s enterprise, and two years later, they published the first high-profile clinical trial of artemisinin in a peer-reviewed Western journal. The same group then conducted the first randomized studies that compared artemisinin alone with the known anti-malarial agents mefloquine and Fansidar (sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine). Artemisinin enhanced effectiveness without adding side effects. Li, Arnold, and others subsequently showed that suppository forms of artemisinin and its derivatives are effective. This mode of drug delivery is especially important for babies and unconscious patients.

Almost every new antimalarial drug has initially slashed incidence of the disease, and then the parasites stop succumbing to it. At that point, sickness and death rates climb again. Small pockets of resistance to artemisinin-based compounds have already cropped up in Western Cambodia. To avoid resistance, patients typically take two drugs that attack the parasite in different ways, and since 2006, the WHO has discouraged use of artemisinin compounds as solo therapies. The organization now recommends several combination treatments, each of which contain an artemisinin-based compound plus an unrelated chemical.

In 2001, the WHO signed an agreement with Novartis, the manufacturer of one of these drug combinations, Coartem®; it consists of artemether and lumefantrine, another antimalarial agent, which was originally synthesized by the Academy of Military Medical Sciences in Beijing. The company is supplying the drug at no profit to public health systems of countries where the disease is endemic. To date, Novartis has provided more than 400 million Coartem® treatments.

Tu pioneered a new approach to malaria treatment that has benefited hundreds of millions of people and promises to benefit many times more. By applying modern techniques and rigor to a heritage provided by 5000 years of Chinese traditional practitioners, she has delivered its riches into the 21st century.

by Evelyn Strauss

Key publications of Tu Youyou

Tu, Y., Ni, M., Zhong, Y., Li, L., Cui, S., Zhang, M., Wang, X., and Liang, X. (1981). Studies on the constituents of Artemisia annua L. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 16, 366-368. (Chinese)

Tu, Y., Ni, M., Zhong, Y., and Li, L. (1981). Studies on the constituents of Artemisia annua L. and derivatives of artemisinin. China J. Chinese Materia Medica. 6, 31-32. (Chinese)

Tu, Y., Ni, M., Zhong, Y., Li, L., et al. (1982). Studies on the constituents of Artemisia annua L. J. Medicinal Plant Res. 44, 143-145.

Tu, Y., Yin, J., Ji, L., Huang, M., and Liang, X. (1985). Studies on the constituents of Artemisia annua L. Chinese Traditional Herbal Drugs. 16, 200-201. (Chinese)

Tu, Y. (1987). Study on authentic species of Chinese herbal drug Qinghao. Bulletin of Chinese Material Medica. 12, 2-5. (Chinese)

Tu, Y. (2004). The development of the antimalarial drugs with new type of chemical structure-qinghaosu and dihydroqinghaosu. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 35, 250-251.

Not often in the history of clinical medicine can we celebrate a discovery that has eased the pain and distress of hundreds of millions of people and saved the lives of countless numbers of people, particularly children, in over 100 countries. The discovery, chemical identification, and validation of artemisinin, a highly effective anti-malarial drug, is largely due to the scientific insight, vision, and dogged determination of Professor Tu Youyou and her team at the Institute of Chinese Materia Medica in Beijing. The statistics on malarial infections are horrendous. Professor Tu’s work has provided the world with arguably the most important pharmaceutical intervention in the last half-century.

Not often in the history of clinical medicine can we celebrate a discovery that has eased the pain and distress of hundreds of millions of people and saved the lives of countless numbers of people, particularly children, in over 100 countries. The discovery, chemical identification, and validation of artemisinin, a highly effective anti-malarial drug, is largely due to the scientific insight, vision, and dogged determination of Professor Tu Youyou and her team at the Institute of Chinese Materia Medica in Beijing. The statistics on malarial infections are horrendous. Professor Tu’s work has provided the world with arguably the most important pharmaceutical intervention in the last half-century.