Graeme M. Clark

University of Melbourne

Ingeborg Hochmair

MED-EL

Blake S. Wilson

Duke University

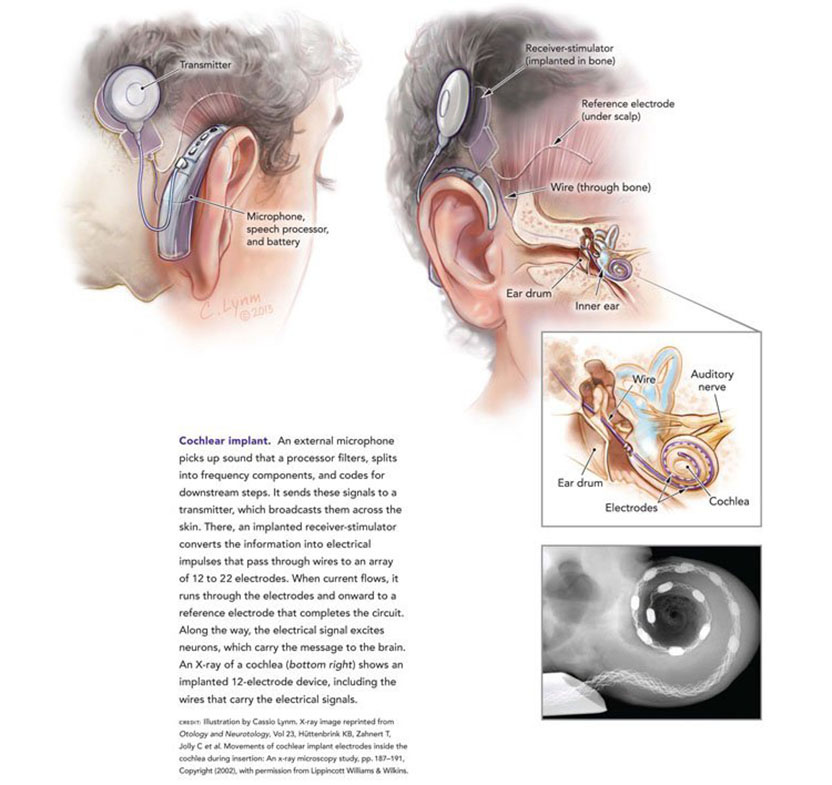

The 2013 Lasker~DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award honors three scientists who developed the modern cochlear implant, a device that restores hearing to individuals with profound deafness. Through their vision, persistence, and innovation, Graeme M. Clark (Emeritus, University of Melbourne), Ingeborg Hochmair (MED-EL, Innsbruck), and Blake S. Wilson (Duke University) created an apparatus that has transformed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. Their work has, for the first time, substantially restored a human sense with a medical intervention.

When hearing fades, so does part of the world. People miss out on conversations, their toddler’s footsteps, and cars screeching around corners. Childhood deafness impairs the ability to understand spoken language and acquire speech, and these hindrances limit educational trajectories and career choices. Cochlear implants return the capacity to communicate and connect through one of the primary conduits used by the vast majority of humans.

Award presentation by Jeremy Nathans

In the New Testament, we read in the Gospel of Mark that Jesus performed the miracle of restoring hearing to a deaf man. Two thousand years later, modern medical science has developed a device that can deliver the same miraculous result, although, I should note, not with the same rapidity as the procedure described in the Gospel. That device is the cochlear implant, which functions as an electronic ear, converting sounds, such as speech, into tiny electrical impulses that activate the auditory nerve.

In the New Testament, we read in the Gospel of Mark that Jesus performed the miracle of restoring hearing to a deaf man. Two thousand years later, modern medical science has developed a device that can deliver the same miraculous result, although, I should note, not with the same rapidity as the procedure described in the Gospel. That device is the cochlear implant, which functions as an electronic ear, converting sounds, such as speech, into tiny electrical impulses that activate the auditory nerve.

Today we honor three pioneers — Graeme Clark, Ingeborg Hochmair, and Blake Wilson — who have devoted their professional lives to making the cochlear implant a reality. Their work, together with the work of many hundreds of engineers, audiologists, and surgeons, has brought the gift of hearing to several hundred thousand profoundly hearing-impaired individuals, a number that is climbing rapidly.

Acceptance remarks

Acceptance remarks, 2013 Lasker Awards Ceremony

I feel very honored to be a co-recipient of the prestigious Lasker~DeBakey Award in Clinical Medical Research, especially as it recognizes research that has led to the multi-channel cochlear implant or bionic ear — the first clinically successful interface between the world and human consciousness. It is also the first advance in helping severely-to-profoundly deaf children communicate since Sign Language of the Deaf began 250 years ago.

My passion to help deaf people started as a teenager when I experienced what it was like for my deaf father as a pharmacist in country Australia — he said years later of his deafness “it has been an enormous handicap, it affects your whole life, there is nothing so embarrassing as not being able to hear people properly.” But in 1967, when I started my research journey there was much skepticism — it had been said “direct stimulation of the auditory nerve fibres with resultant perception of speech is not feasible.”

Nevertheless, I commenced an uncertain journey by leaving a senior surgical position to do research in auditory brain science. And when I discovered in 1970 that multi-channel electrical stimulation would be needed there was nowhere to go to further the research. Fortunately, the University of Melbourne appointed me to establish the first ENT and audiology departments in Australia, but I still had few staff and little money. I pay tribute to the young graduates who shared the vision, stood on the streets of Melbourne shaking a tin and asking for money, and turned the ENT Department into an engineering one.

When all was ready, I interviewed my first experimental patient, Rod Saunders, in 1978. He said: “I would like to be able to hear something again. It’s a nightmare being deaf. If it helps with speech I will be very grateful.” It has also been a means of learning about brain function and what underlies human consciousness. I can now say after a tumultuous ride personally, that Rod and many thousands like him can now have their life back again. This has been in no small measure due to an exciting partnership with Cochlear and their leadership in biomedical technology.

In conclusion, I would to thank the Lasker Foundation again for this honor, and I will endeavor to continue my search for excellence to help deaf people and others with neurosensory disorders such as blindness and paraplegia.

Acceptance remarks, 2013 Lasker Awards Ceremony

The cochlear implant is not a life-saving device. It is, however, very, very special, since it has to do with communication, with being able to take part in society. It is connected with every child’s human right for education, and it can alleviate isolation and cognitive decline in older adults.

Clinical medical research is of particular importance in the field of CIs for at least three reasons:

Efficacy with CIs has to do with how well the sensory organ is replaced, it has to do with perception.

Secondly, since learning is involved with electrical stimulation, immediate and acute results of sound perception tests do not necessarily represent what the user will be able to perceive after getting used to the new input to their auditory system.

And thirdly, another very special aspect of cochlear implants is the enormous responsibility researchers and developers have to gently preserve the tiny delicate structures of the inner ear for future technologies. This is of special relevance with children born today with a life expectancy of maybe 120 years and with candidates who nowadays typically have hearing still present, that they hope and expect to be preserved.

Acceptance remarks, 2013 Lasker Awards Ceremony

Development of the modern cochlear implant was a worldwide effort involving many scientists, engineers, physician-scientists, and research subjects. The success of this effort is an outstanding example of the power of collaborations between the public and private sectors and also the informed support by the NIH of applied as well as basic research.

I am proud to stand before you today as a representative of the worldwide effort, and I am especially proud to stand with Graeme Clark and Ingeborg Hochmair, who are two of my heroes and the foremost living pioneers in our field.

Although the present cochlear implants are truly wonderful, room still exists for improvements. A variability in outcomes remains, and even the top-performing patients experience difficulties in understanding speech in adverse acoustic environments such as noisy restaurants or workplaces. In addition, reception of sounds more complex than speech — such as music — is less than satisfying for most patients. Research is underway to narrow or even eliminate these gaps between prosthetic and fully functional hearing, and to narrow the range of outcomes such that all patients will achieve high levels of performance. Many promising possibilities are being pursued by extraordinarily talented investigators, and I am completely confident that further improvements will be made.

An even more important challenge — in my mind — is to make the highly effective technology we have today available to all persons who could benefit from it. Thus far, about 320 thousand persons have received a cochlear implant in one or both ears. But various estimates indicate that as many as 25 million persons worldwide could benefit from a cochlear implant. That means that only about 1 or 2 percent of the population who could benefit actually have received a cochlear implant.

The cochlear implant is a transformative technology that allows children to be mainstreamed into regular schools, adults to have a wide range of job opportunities, and all recipients to connect in new and important ways with their families, friends, and society at large. The resulting human and economic benefits are immense.

In many parts of the world, cost is a barrier to widespread applications of the technology, even though the benefits ultimately far outweigh the cost. The principal expenses are in providing the appropriate medical infrastructure and care. The cost of the device also plays a role, but that cost is coming down and is not the dominant factor for most countries. Several of us in this room are working to reduce or remove the cost barrier, and to improve hearing health care worldwide, which includes prevention, screening, and treatments in addition to cochlear implants.

This magnificent award will greatly increase awareness of how cochlear implants can enable severely and profoundly deaf persons to realize their full potential in life, and that awareness will in turn facilitate further dissemination and development of this marvelous technology. Thank you for welcoming Graeme, Ingeborg, and me into the Lasker family, and thank you for the highly favorable tailwind you have given us and our colleagues to do more!

Interview with Graeme M. Clark, Ingeborg Hochmair, and Blake S. Wilson

Video Credit: Susan Hadary