Illuminating thoughts. Freudian psychoanalytic theory dominated the field of psychiatry until Aaron T. Beck devised cognitive therapy, a treatment that focuses on the conscious rather than the unconscious. In Beck’s approach, the therapist and patient together identify the automatic thoughts that cause the patient’s emotional and psychological distress. They then work toward challenging this distorted way of thinking. [“The Pleasure Principle,” by René Magritte: C 2006. Herscovici, Brussels/ARS, New York]

Different ways of thinking

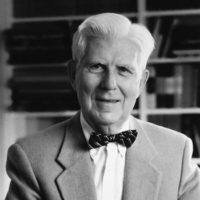

In 1956, Aaron T. Beck finished his training as a Freudian psychoanalyst, attracted to the field by its promise to improve people’s lives. In discovering unknown continents of the mind, the ideology went, psychoanalysis offered unprecedented possibilities by helping individuals overcome the unconscious drives and desires that thwart their sense of well-being and ability to function. Many psychiatrists were skeptical about this method because its impact had not been documented scientifically. In the late 1950s, Beck decided to perform studies to establish its effectiveness. Instead of confirming the tenets of psychoanalytic theory, he showed that this approach omits a crucial root of psychological suffering.

Depression plagued the majority of Beck’s patients, so he focused on that illness. According to Freud, depression arises from unconscious — and unacceptable — anger toward another person. Instead of expressing this hostility outwardly, depressed people direct it toward themselves. Psychoanalytic theory predicted that this rage manifests itself in dreams. Beck found, however, that depressed patients don’t dream about anger; they dream about loss and personal inadequacy.

Perplexed at the apparent failure of the conventional theory to pass this fundamental test, Beck revised his proposal and subjected it to additional tests. Repeatedly, his observations refuted his hypotheses. Beck gradually discovered that depressed patients in their conscious lives hold the same view of themselves as that expressed in their dreams: They feel like losers.

While probing and developing these ideas, he realized that people seized by depression often have exaggerated and bleak ‘automatic thoughts’ that trigger uncomfortable feelings. For example, self-criticism, without preceding anger, can prompt feelings of sadness or loneliness. Instead of discarding this observation that contradicted psychoanalytic theory, Beck grabbed onto it. He proposed that these internal messages foster patients’ problems. The distorted view grips them, warping their self-perceptions, deflating their hopes and expectations, and making suicide seem like a reasonable escape from unrelenting pain.

These realizations and ideas opened up a previously unexplored inner realm and provided the framework for the theory of cognitive therapy. As people enter depression, they filter out positive information about themselves and amplify negative information, Beck speculated. Patients view themselves as defective and helpless; their future seems hopeless and their lives seem full of insurmountable problems.

These ideas reformulated the core problem in depression: It does not arise from unconscious drives and defenses, as psychoanalytic theory held, but from unduly negative beliefs and bias against oneself. Beck had uncovered a major cause of depression — and one that had been overlooked by the major theoretical perspectives of the time. Neither Freudian therapy nor the other major therapy of the day — behavior therapy, which posited that psychological disturbances resulted from outside forces and could best be resolved by changing the external environment — put stock in the notion that a patient’s beliefs, thoughts, or expectations generate distress.

By 1961, Beck had abandoned psychoanalysis. Instead, he was zeroing in on particular instances in which patients felt bad and asking what thoughts immediately preceded the uncomfortable emotion. He then coaxed patients to apply the scientific method to their beliefs, urging them to examine the evidence. A woman who felt worthless might reveal that, immediately before her mood plummeted, she had thought, “I’m a bad mother.” Beck would probe further to unearth the apparent basis for this internal statement, and then ask questions such as, “When siblings from other families fight with one other, does that mean their parents are doing a bad job?” “If the neighbor children went to school without their boots or forgot their lunches, would you condemn their mother?” With this approach, he prodded patients to assess the accuracy of what they were telling themselves. As they began to gain objectivity, their self-images started to improve, and their problems cleared up. He noticed significant changes almost immediately. After 10-12 weekly sessions, patients’ symptoms had usually resolved. Beck had developed a short-term therapy for depression.

By 1964, Beck had laid out the foundations of his theory and practice. These revolutionary ideas encountered resistance, but he went on to demonstrate that his new cognitive therapy altered patients’ feelings and behaviors quickly and in an enduring way.

Better than drugs

In the 1970s, Beck conducted the first rigorous study of any type of ‘talk therapy’. He pitted cognitive therapy against the best antidepressant drug at the time — imipramine — in a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial designed to test how effectively these two approaches ameliorated symptoms of a particular disorder: depression. In this head-to-head comparison, cognitive therapy outperformed the drug after a treatment period of up to 12 weeks. Furthermore, the benefits persisted a year later. In contrast, the effectiveness of psychoanalysis, whose normal course is years, has not been proven, as it has not been subjected to this type of randomized, controlled study. This work established cognitive therapy as a powerful clinical intervention and set a new standard for evaluating the effectiveness of any kind of psychotherapy. Numerous studies since then have reaffirmed that the approach is equal or better at combating depression than are antidepressant drugs; furthermore, it is better at preventing relapse.

Beck and his trainees spent the next three decades adapting cognitive therapy to treat additional problems—such as anxiety disorders, panic disorders, and social phobias—and testing its utility. As part of this enterprise, he developed powerful instruments with which to measure the severity of symptoms associated with various psychiatric illnesses. Prior to this work, a dearth of techniques for measuring the severity of such disturbances hampered psychiatric research.

Saving lives

Among his major achievements, Beck has made dramatic advances in helping people with suicidal urges, in part by providing a classification and assessment scheme for predicting suicidal behavior. Beck recognized that the feeling of hopelessness is crucial for evaluating suicidal patients. He developed a “hopelessness scale” — a series of simple questions — that measure the degree to which an individual feels as if current problems are solvable. Beck and his colleagues have tracked patients for more than 30 years, and have found that this tool can indicate the likelihood of a person to commit suicide, particularly for individuals at high risk. In a seven-year study of 1958 outpatients, the test pinpointed 16 of the 17 people who killed themselves during that period; individuals who scored above a particular hopelessness rating were eleven times more likely to commit suicide than were the low scorers. Thus, the risk of hopeless patients eventually dying as a result of suicide was approximately the same as that of heavy smokers dying from lung cancer.

In 2005, Beck and his colleagues published a paper that demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive therapy for suicidal individuals. 120 patients who were evaluated at an emergency room immediately after a suicide attempt received support and referrals from a caseworker; half of these patients underwent 10 sessions of cognitive therapy in addition. Participants in the cognitive-therapy group were almost 50 percent less likely than non-participants to attempt suicide during the 18-month follow-up period.

In the United States, more than 30,000 people die each year from suicide, making it the eleventh leading cause of death; among people between the ages of 15 and 24, it is the third biggest killer. Worldwide, suicide is among the three leading causes of death among individuals between 15 and 44 years old. Because Beck has invented a simple tool with which to predict future suicidal behavior and a therapy that dramatically reduces attempts, his work has enormous potential for slashing those figures. Furthermore, it could tremendously benefit especially high-risk populations, such as those on college campuses.

Soothing mental distress around the globe

Cognitive therapy has become a mainstay in the practices of many mental health practitioners worldwide. The American Psychiatric Association’s guidelines state that cognitive behavioral therapy (an offshoot of cognitive therapy) is one of the two best-documented psychotherapies for treating major depression. Health systems in Europe recommend it for treating a number of common psychiatric disorders. Inspired by the success of cognitive therapy in curing depression, the United Kingdom’s Department of Health is launching a $6.8 million pilot program aimed at significantly increasing access to ‘talk’ therapies. If results are favorable, the government will expand the program and expects to save millions of dollars by helping people with mild to moderate depression get back to work and off disability benefits.

Beck’s development of cognitive therapy and his discovery that it effectively treats serious mental illnesses has major public health significance. Countless individuals owe their sense of well-being — and their lives — to Beck’s work.

by Evelyn Strauss

Key publications of Aaron Beck

Beck, A.T. (1963). Thinking and depression. Arch. Gen. Psych. 9, 324–333.

Beck, A.T. (1964). Thinking and depression II. Theory and therapy. Arch. Gen. Psych. 10, 561–571.

Beck, A.T., Hollon, S.D., Young, J.E., Bedrosian, R.C., and Budenz, D. (1985). Treatment of depression with cognitive therapy and amitriptyline. Arch. Gen. Psych. 42, 142–148.

Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., and Garbin, M.G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin. Psych. Rev. 8, 77–100.

Beck, A.T. (2005).The current state of cognitive therapy: A 40-year retrospective Arch. Gen. Psych. 62, 953–959.

Brown, G.K., Tenhave, T., Henriques, G.R., Xie, S.X., Hollander, J.E., and Beck, A.T. (2005). Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 294, 563–570.

Butler, A.C., Chapman, J.E., Forman, and Beck, A.T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clin. Psych. Rev. 26, 17–31.

By the end of the 19th century, the discoveries of medical pioneers such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch had led us into the era of modern medicine. They understood disease to be caused by some physical disturbance rather than evil spirits or an imbalance of the humours. This was not just an advance for those suffering from illnesses that wiped out whole townships, but it also spelled progress for the insane. Neurologists began to show that brain diseases such as syphilis or tumors could produce bizarre changes in personality. Even if treatments were slow to come, the insane could be viewed with more compassion, as suffering actual brain damage rather than demonic possession.

By the end of the 19th century, the discoveries of medical pioneers such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch had led us into the era of modern medicine. They understood disease to be caused by some physical disturbance rather than evil spirits or an imbalance of the humours. This was not just an advance for those suffering from illnesses that wiped out whole townships, but it also spelled progress for the insane. Neurologists began to show that brain diseases such as syphilis or tumors could produce bizarre changes in personality. Even if treatments were slow to come, the insane could be viewed with more compassion, as suffering actual brain damage rather than demonic possession.