What makes a good mentor, and how do you find the right mentor for you? We asked past Essay Contest winners about their mentorship experiences. They provided us with three useful tips on how to develop mentoring relationships in academia: find a mentor who supports your goals, prioritize communication, and seek out different perspectives.

Find a ‘gardener,’ not a ‘sculptor’

It can be intimidating to search for a mentor, especially if one is just starting out and only has a limited network. A good place to begin is to look for “someone who is genuinely invested in their students” and sees them as individuals rather than just helping hands in the lab, says Peter John, a MD-PhD student at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Part of the challenge for advisors is to understand that mentoring is not a one-size-fits-all approach, adds Peter Soh, a neurology resident at the University of South Alabama. “Not every trainee is going to get from point A to point B in the same way,” he says.

Paul and his mentor Margot Kushel, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Vulnerable Populations at UCSF.

It’s important that mentors take the time to understand a student’s individual goals, even if those goals do not follow the mentor’s own career path, says Dereck Paul, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). He refers to this as the ‘gardening’ model, in contrast to a ‘sculpting’ approach. “Instead of trying to sculpt the mentee in their own image, great mentors try hard to understand who their mentee is and where they are coming from, and then provide them with what they need to grow to their full potential,” he says, adding that great advisors also anticipate that mentees may need guidance that spans beyond issues directly related to the workplace.

Communication is key

To maintain a successful mentor-mentee relationship, both participants need to communicate effectively. For potential mentors, the first step is broadcasting that they want to take on mentees, advises Abigail Cline, a dermatology resident at New York Medical College, because asking someone to be a mentor can be awkward and intimidating for some students. “Shout it from the rooftops! Students may not know a potential mentor’s expertise, schedule, or abilities,” she says. Another key step is reaching a mutual understanding about the expectations of the mentor-mentee relationship. Cline emphasizes that students need to be clear about what they want from a mentor. Likewise, mentors should be honest about their availability and what they have to offer the student, notes Debra Shamala Karhson, PhD.

Students have their own responsibilities in maintaining a mentor-mentee relationship. “Like a good mentor, a good mentee is personable, honest, and motivated,” says Soh. A student should actively seek out advisors with expertise in his or her areas of interest, says Grace Beggs, a PhD student from Duke University. She advises that mentees communicate their professional development goals to their mentors and “educate themselves enough to ask their mentors insightful questions.” Students can also take initiative by scheduling meetings and requesting mentor feedback on deliverables, adds Karhson. Even after a student has moved on from a mentor, Cline notes, discussing what worked and what did not work in the relationship can help advisors and advisees optimize future mentoring approaches.

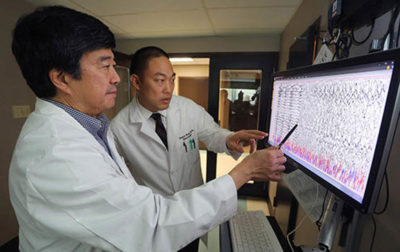

Peter Soh reviews data with his mentor Dean Naritoku, professor and chair of neurology at the University of South Alabama. (Credit: Bill Starling/USA Health)

There is no consensus on whether the mentor or mentee will be the driving force in the relationship. In Cline’s opinion, potential mentors should at least meet the student halfway, especially when first establishing a mentor-mentee relationship. “The student’s initiative alone is often not enough to make that connection,” she says. Now that Karhson has served as a mentor for multiple students, she finds it best when she “places the power in the hands of the mentee.” She expects that students will initiate conversations and tell her what they are struggling with, and in turn, it is her job to listen, ask questions, and provide insight.

(Left to Right): Debra Shamala Karhson with former mentees Michael Mariscal, Sophie Rose, and Jesus Madrid.

Seek out multiple mentors

When searching for mentors, a student may tend to home in on one individual; however, such a narrow focus can be limiting, says Karhson. Throughout her academic journey, Karhson has had both traditional advisors, such as associate and full professors, and what she calls ‘beta’ mentors – individuals just a few years ahead in their scientific careers. “Students should have a panel of mentors that provide them with different perspectives,” she says. Advisors can help students build these panels and expand their professional networks by introducing the mentees to other scientists, notes Beggs.

Multiple mentors are almost a necessity for MD-PhD students, says John, because “if someone hopes to bridge the two different worlds [of clinical medicine and research], he or she needs to have people who have experience in each field.” David Hartmann, a MD-PhD student at the Medical University of South Carolina, integrated the perspectives of multiple advisors to help guide his education and career. “My mentor [Andy Shih, now at Seattle Children’s Hospital] taught me how to be a scientist – for example, how to write grants and network at conferences,” he says. To augment this and figure out which medical specialty to pursue and where to apply for residency, David sought out advice from clinicians. He likens mentorship to other support systems in life: “You can’t just have one friend who does it all… We need a lot of people to get us where we want to go.”

By Lucy Hicks