David J. Weatherall

Oxford University

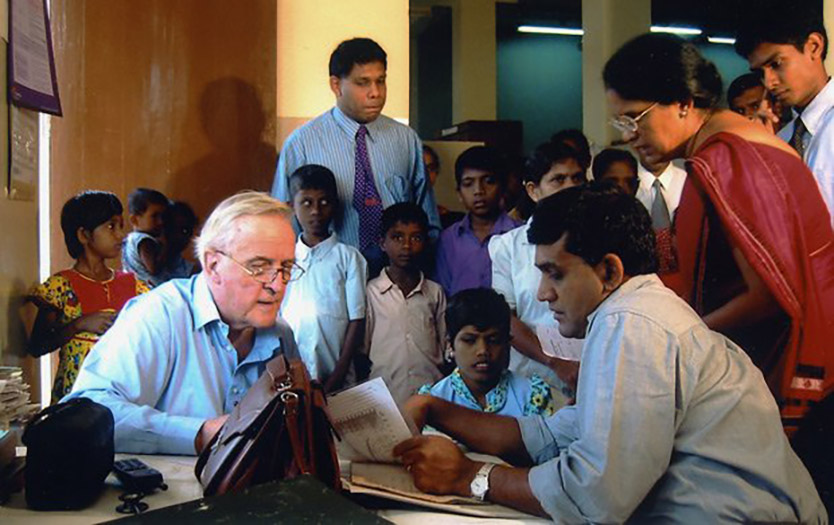

For 50 years of international statesmanship in biomedical science — exemplified by discoveries concerning genetic diseases of the blood and for leadership in improving clinical care for thousands of children with thalassemia throughout the developing world.

The 2010 Lasker~Koshland Award for Special Achievement in Medical Science honors a physician-scientist who has melded astute bedside observations with rigorous experiments to generate countless insights about inherited blood disorders, especially thalassemia. In the last half century, David J. Weatherall (Oxford University) has deployed diverse investigational approaches that have catalyzed advances in our understanding of the biochemical, genetic, and clinical aspects of thalassemia and has delivered fruits of this wisdom to patients worldwide. Weatherall made global health a priority before doing so was fashionable, and he has inspired scores of young physicians and researchers to apply the power of molecular medicine.

At the beginning of his career, Weatherall pursued his interest in thalassemia despite lack of support. He almost got court-martialed for his first paper, on a Nepalese patient he had studied during a late 1950s stint in the British Army, because he had not gotten permission from military commanders to publish. Furthermore, a senior officer disapproved of broadcasting the fact that one of its regiments had “bad genes.” Later, a medical thesis examiner suggested that he switch to psychiatry rather than study an obscure disease. Fortunately, Weatherall persevered.

Award presentation by Lucy Shapiro

Sir David Weatherall is the most respected clinical scientist of his generation. He has been knighted, his portrait hangs in the UK National Portrait Gallery, and there is an institute at Oxford that carries his name. Behind these accolades is a gentle, wry man with a deep passion for understanding the molecular basis of disease and its application to the health of his patients. Along the way, he has changed the training of physician-scientists and medical practice in the developing world.

Sir David Weatherall is the most respected clinical scientist of his generation. He has been knighted, his portrait hangs in the UK National Portrait Gallery, and there is an institute at Oxford that carries his name. Behind these accolades is a gentle, wry man with a deep passion for understanding the molecular basis of disease and its application to the health of his patients. Along the way, he has changed the training of physician-scientists and medical practice in the developing world.

David was raised and educated in Liverpool. Upon completing his medical degree in the late 1950s, he was asked where he’d like to do his obligatory National Service. Being petrified of flying, fighting, and snakes, he opted for service in London. The British Army promptly sent him to Singapore, where he first did a six-month stint in surgery, after which his surgical boss told him that on no account should he be let loose as a surgeon. When he next moved on to spend six months on a medical service, he carefully explained to the powers that be that his only experience was in adult medicine. He was promptly put in charge of a children’s ward. This turned out to be a seminal event not only in David’s life and career, but an event that ultimately has had a significant impact on world health.

Acceptance remarks by David J. Weatherall

Acceptance remarks, 2010 Lasker Awards Ceremony

In thanking the Lasker Foundation for this wonderful honor, my current mood is one of enormous pleasure tinged with total disbelief. The latter is engendered by the fact that my first effort at research into common inherited anemias was an embarrassing disaster. After qualifying in medicine in Liverpool in 1956 and an internship, I received my call-up papers from the British army to serve what was then a compulsory two years of National Service. Terrified of violence, flying, or snakes, I volunteered to serve in the UK; three weeks later I found myself on a troop ship bound for Singapore, where I was put in charge of the Childrens Ward at the British Military Hospital. There I encountered a Nepalese baby whose father was serving with a Ghurka regiment and who was profoundly anemic and being kept alive on blood transfusion. I discovered that this child had thalassemia, which at that time was thought to be a disease of Mediterranean populations. I thought the world should hear about this and published a case report of this child as my first paper. Shortly afterwards I was told to come and see the head of the Armed Forces for the Far East, who asked me whether I had had permission from the British government to publish this work. I said I hadn’t, and he told me that to publish details about British military personnel without permission was an offense for which I could be court-martialed. “Never do it again,” he said, “and anyway it is extremely bad form to tell the world that our best regiments have bad genes.” Fortunately, I ignored this first piece of career advice.

Interview with David J. Weatherall

Video Credit: Susan Hadary