Michael Sheetz

Columbia University

James Spudich

Stanford University School of Medicine

Ronald Vale

University of California, San Francisco

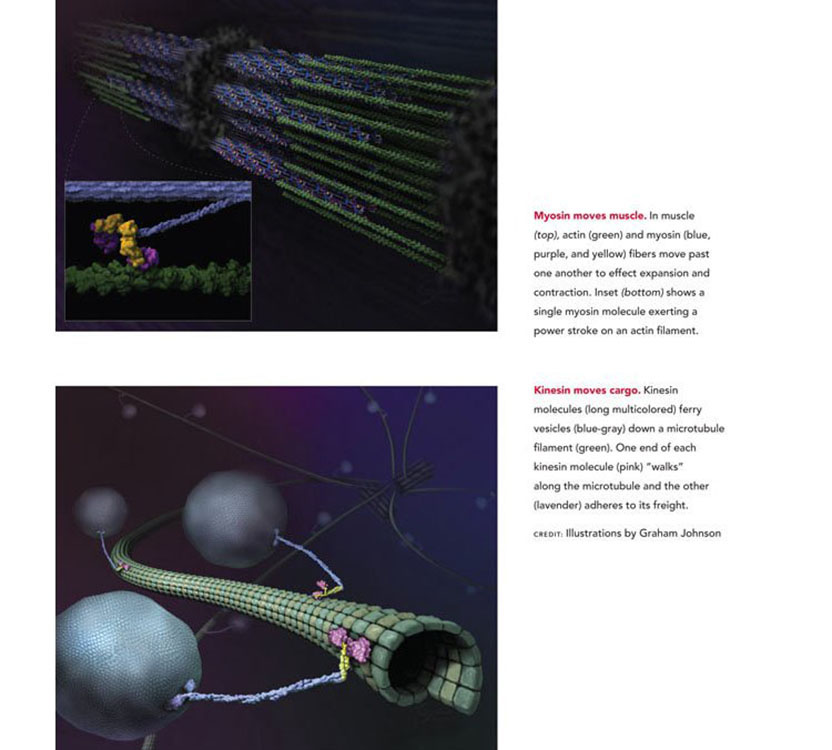

The 2012 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award honors three scientists for their discoveries concerning cytoskeletal motor proteins, machines that move cargoes within cells, contract muscles, and enable cell movements. By developing systems that allow reconstitution of motility from its constituent parts, Michael Sheetz (Columbia University), James Spudich (Stanford University School of Medicine), and Ronald Vale (University of California, San Francisco) established ways to study molecular motors in detail. These accomplishments enabled the discovery of the motor protein kinesin and unveiled the steps by which these engines convert chemical energy into mechanical work. The miniscule motors underlie numerous vital processes, and the landmark achievements of Vale, Spudich, and Sheetz are driving drug-discovery efforts aimed at cardiac problems as well as cancer.

Since 1774, when microscopist Bonaventura Corti discovered “torrents” of fluid inside plant cells, scientists have known that even tiny units of life bustle with motile activity. By the mid 1900s, researchers had observed chromosome separation during cell division and discovered that material travels long distances within nerve cells, but existing methods could not untangle these processes. Throughout most of the 20th century, the study of biological movement focused on muscle contraction, an activity that is fueled by the energy-rich molecule ATP.

Award presentation by Cori Bargmann

In the 12th century, religious monks of the Benedictine orders labored in the Scriptorium, where they copied and proofread religious texts and the manuscripts of antiquity. But other monks took the orders of “The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Jesus Christ and the Temple of Solomon,” also called “the Knights Templars,” and these were men of action: soldiers in the Crusades and movers of trade, people, and resources throughout Europe and the Middle East.

In the 12th century, religious monks of the Benedictine orders labored in the Scriptorium, where they copied and proofread religious texts and the manuscripts of antiquity. But other monks took the orders of “The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Jesus Christ and the Temple of Solomon,” also called “the Knights Templars,” and these were men of action: soldiers in the Crusades and movers of trade, people, and resources throughout Europe and the Middle East.

The Lasker prize has recognized many basic science discoveries in the cellular equivalent of the Scriptorium. When we talk of DNA and RNA, we talk of replicating, transcribing, and translating the information of the genome — the copying and proofreading activities of the Benedictine monks. But this Lasker prize recognizes action: the mechanisms by which cells move, disseminate their subcellular components, and generate force. Our honorees, Jim Spudich, Mike Sheetz, and Ron Vale, showed how cells use the force-generating molecular motors myosin and kinesin to drive biological processes that include muscle contraction, the heartbeat, cell migration in development, cell division, and the orderly delivery of molecular components to each part of each cell.

Acceptance remarks

Acceptance remarks, 2012 Lasker Awards Ceremony

Science is a collective effort. I am delighted that Tom Reese and Bruce Schnapp — with whom Jim and Ron and I shared a close collaboration — could be with us today. Together we spent many forgettable days dissecting squid axons and brains in the cave (a windowless room filled with running seawater tanks) — but there were a few great days that made it all worthwhile. The joy of discovery is almost universal and goes far back in history. A particularly apt description comes from Kepler in 1596 upon his discovery that the tracks of the planets could only make sense if you assumed that the planets traveled around the sun. Kepler wrote, “This was the occasion and success of my labors. And how intense was my pleasure from the discovery can never be expressed in words. I no longer regretted the time wasted. Day and night I was consumed by the computing. To determine whether this idea would agree with the Copernican orbits, or if my joy would be carried away by the wind. Within a few days everything worked, and I watched as one body after another fit precisely into its place among the planets.” Those feelings are impossible to share but priceless when they occur.

Since that time, Ron, Jim, and I have been interested in fostering multi-disciplinary collaborative environments, because we all agree that they are the best way to stimulate discovery-driven science: Jim through Bio-X and efforts in Bangalore, Ron through his many service and education efforts both in the US and India, and I through interdisciplinary centers in the US and Singapore. The pace of discovery has always been greater when new technologies are brought to old problems (case in point was the use of video to quantify motility in vitro). By bringing together the latest technologies of engineers and physicists with the problems of biology and medicine in an open, communicative environment, it has been and will be possible to discover many important aspects of the biological systems that underlie disease and regeneration in humans and animals. There is hope that the pace of substantive discovery will increase and the next generation can have a much better understanding of and ability to improve human health, assuming that the future of biomedical research is not derailed by lack of funding.

Over the twenty-five-plus years since these stories unfolded, I have enjoyed many additional collaborations, but none were as successful or as exciting as this one was. The wonderment of seeing microtubules moving on a glass coated with axoplasmic proteins cannot be adequately described. I cannot thank everyone who made it possible for me to be in that cinderblock basement lab at 1 AM, but I will be forever grateful. To paraphrase Bruce Springsteen: I hope when I get old I don’t sit around thinking about it, but I probably will. Trying to recapture a little of the glory of and the boring stories of glory days. Thank you.

Acceptance remarks, 2012 Lasker Awards Ceremony

I am deeply honored to share the Lasker Award with my good friends Ron Vale and Mike Sheetz. We have been asked to speak about what science means to us. First of all, for me there is the pure joy of discovery. I so much appreciate that I can still spend time in my boyhood pursuit of understanding how things work. Interestingly, there are two distinct aspects of the daily life of a scientist — one is very private and requires solitude, and the other demands extensive networking with other individuals, both fellow scientists and people from other walks of life. Creativity in science requires both the solitude and the community interactions.

On the one hand, a scientist is like the artist who sits on a hillside in the solitude of the setting sun and tries to capture the magic of the moment on her canvas, or a musician who spends hours in the privacy of a quiet space, striving to construct something beautiful and meaningful. I am grateful to have been able to spend nearly my entire life exploring the beauty of biology, to challenge my creativity, and to contemplate, often in solitude, the underlying basis of biological problems I have worked on. As is true for the artist and the musician, that solitude is essential for creativity to emerge.

But science also is a community enterprise and as a member, one enters into fruitful collaborations, which often lead to insights that neither party may have made alone. Then there is the opportunity to train others, and I have had the privilege to train more than 100 very bright students over my career; they remain members of my personal scientific family.

As scientists we also have opportunities, even obligations, to try to translate our discoveries for meaningful clinical use. This requires interactions with entirely different sectors of the community, including the business world. And with such interactions, there are now potential drugs in clinical trials having to do with molecular motors.

Finally, I credit in large part the strong public education system in this country for making it possible for an individual like myself, coming from a small town in Illinois of population under 1000, to stand before you today. I want to make a strong plea that all of us, from all sectors of society, work together to return our public education system to where it should be to make it possible for our grandchildren to have the opportunities we did. Thank you very much.

Acceptance remarks, 2012 Lasker Awards Ceremony

It is wonderful to share this day with my friends Mike Sheetz and Jim Spudich. I believe this honor is not only directed to the three of us, but to the field of biology that we represent and the many scientists who have contributed to our understanding of molecular motors.

Many serendipitous events led to my being part of this award. In 1980, I applied to the Stanford MD/PhD program, and as fate would have it, I interviewed with Jim Spudich. Jim and I hit it off instantly, a preview of what would become a long friendship with Jim and his family. It was relayed to me much later that Jim’s recommendation carried the day and led to my admission to Stanford.

I chose Eric Shooter as my thesis advisor initially because of his great scientific reputation in combining biochemistry with neuroscience, my areas of interest. As fate would have it, beyond his preeminence as a scientist, Eric was a wonderful advisor who would support my wide-ranging scientific interests.

Meeting Mike Sheetz and learning about his experiments with Jim provided ideas for new experiments on axonal transport using the squid as a model system. As fate would have it, Mike and I failed to obtain squid in 1983 in California, because an El Niño caused their disappearance from the coast that year.

The initial disappointment brought by El Niño turned out to be a blessing in disguise, because it forced us from California to the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Who would have a thought that a meteorological disturbance would play such an important role in my career? As fate would have it, the move to MBL allowed us to team up with Bruce Schnapp and Tom Reese and to become exposed to the technique of video microscopy, just recently pioneered by Robert Allen and Shinya Inoue. And as fate would have it, I succeeded in getting in vitro assays for axonal transport to work just a couple weeks before I was supposed to start my medical school clerkships at Stanford. I cancelled my trip home, thinking that my MD was only temporarily postponed. However, as fate would have it, I still have not found a pause in the excitement of doing science, working together with the many bright students and postdocs in my lab, to step aside and complete my MD.

The Lasker Award provides a time for retrospection. Looking backwards, one can appreciate the series of fateful events that have brought Jim, Mike and me together, along with friends who shared in this journey, on this special day in New York City.

However, the reputation associated with the Lasker Award carries with it an implicit forward-looking obligation. It is a beginning, not an endpoint. As recipients of the Lasker, we should act as stewards of our profession, promoting the research and careers of young scientists worldwide so that they can make the next round of discoveries. We also are living in a time when communicating the process, excitement and importance of science to the general public, to our government, and to students in our school systems has become more important than ever. In addition to creating new knowledge, we scientists should devote some of our time to reach out and convey a spirit of partnership with the society that supports our work. Mary and Albert Lasker were true pioneers and innovators in this regard. By their example, one can appreciate that such matters are too important to leave to chance or fate; rather, they require vision and hard work. I will do my best to carry out this important mission and legacy of the Laskers.

Interview with Michael Sheetz, James Spudich, and Ronald Vale

Video Credit: Susan Hadary