Shirley Tilghman was president of Princeton University between 2001 and 2013. She was elected to this post after serving on the Princeton faculty for 15 years and was the first woman to hold the position. During her scientific career as a mammalian developmental geneticist, Tilghman studied the ways in which genes are organized in the genome and are regulated during early development. In 1998, Tilghman was named the founding director of Princeton’s multidisciplinary Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, and she was one of the founding members of the National Advisory Council of the Human Genome Project for the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Tilghman has received numerous awards for her scientific work and her distinguished teaching, and she has been invited to serve on corporate and college trustee boards. Tilghman initiated the Princeton Postdoctoral Teaching Fellowship, a program that brings postdoctoral students to Princeton each year to gain experience in both research and teaching, and she established a steering committee on undergraduate women’s leadership at the university.

Shirley Tilghman was president of Princeton University between 2001 and 2013. She was elected to this post after serving on the Princeton faculty for 15 years and was the first woman to hold the position. During her scientific career as a mammalian developmental geneticist, Tilghman studied the ways in which genes are organized in the genome and are regulated during early development. In 1998, Tilghman was named the founding director of Princeton’s multidisciplinary Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, and she was one of the founding members of the National Advisory Council of the Human Genome Project for the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Tilghman has received numerous awards for her scientific work and her distinguished teaching, and she has been invited to serve on corporate and college trustee boards. Tilghman initiated the Princeton Postdoctoral Teaching Fellowship, a program that brings postdoctoral students to Princeton each year to gain experience in both research and teaching, and she established a steering committee on undergraduate women’s leadership at the university.

Q: You made your first groundbreaking discoveries related to cloning the first mammalian gene while still a postdoctoral fellow at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Tell us more about what factors contributed to this early success and how that affected the next steps of your career.

A: I am a perfect example of what many studies have shown, which is that the earlier you can get women into laboratories, conducting research, and the more often you can give them a positive experience in discovery, the more likely they are to continue in science. I was very lucky as an undergraduate to have the experience of working in faculty labs during the term and in the summers. I published two papers as a result of my undergraduate research, so by the time I got to graduate school, I — as they say in ABC Sports — knew the thrill of discovery. That increased my excitement about becoming a scientist and my confidence that I could succeed. I also had a very positive experience as a graduate student with a wonderful mentor, Richard Hanson. So by the time I got to my post-doc at the NIH, I was both fairly confident and really committed to a career in science.

Tilghman with graduate student Ekaterina Semenova examining a biological sample

Q: How do your early years as a young investigator compare to the current settings in which young scientists begin their careers?

A: The beginning of my independent career could not have been more different from what I see at Princeton, and at all of the institutions that I am visiting now, watching young investigators trying to establish their labs. First and foremost, it never really occurred to me that I would not get funding. The NIH funding rate at the time was in the neighborhood of 35%. I knew that if I wrote a good grant, I would get funded. The kind of anxiety about funding that we see today simply didn’t exist. Second, there was something really special about the Institute for Cancer Research, where I began my independent career, in that it made it possible for me to focus 100% of my time on science. That is a real luxury today. There are some institutions that still provide that kind of environment, but they are few and far between. So my experience does not reflect, I think, what young investigators are facing today.

Q: Is there something young scientists can do today to overcome the difficulties that are particular to the present time?

A: The responsibility does not lie with the young faculty. The responsibility for making the environment more conducive to young investigators, getting their careers off quickly, and allowing them to focus on their science frankly lies with the scientific leadership. The scientific leadership has not been willing to look hard at the experiences of young investigators and ask whether there are aspects of our entire enterprise that are making it much more challenging for young people to get up and running, and to be creative and successful.

Q: What are some of the more memorable setbacks that you’ve had as a scientist, and how did you overcome them?

A: The hardest thing for a scientist is to acknowledge that an idea he or she is pursuing is simply not going to work. When you have invested a lot of time, energy, and money into a project, figuring out when to cut your losses is the hardest thing. I don’t have any magic formula for doing that, but scientists need to go into every project knowing that there is some finite possibility that in a year or two years or (God forbid) three years, they are going to have to pull the plug. And every time I had to do that on a project, and I did, it felt like a huge setback. But it was absolutely essential to do it because I was just going down a black hole.

Q: You are both a very successful scientist and a very accomplished administrator. What drives your passion for each, and what contributed to your success?

A: One could argue that as a scientist the passion comes from wanting to know the answer. I could always tell which of my students and fellows was going to ultimately succeed because he or she was the one that just could not stand to not know the answer to the question that they were pursuing. This deep intellectual curiosity is what drives the best science. The passion that I felt as president of [Princeton] University grew out of a deep commitment to an institution that had made it possible for me to have a wonderful scientific career. My role was to enhance the quality of the university by enhancing the experience of its students, faculty, and staff, and it seemed like a wonderful way to give back to an institution that had been very good to me.

Q: You have mentioned in the past that being invited to run for president of Princeton was one of the most surprising and abrupt turns in your career. Can you tell us just a little bit more about how it happened?

A: The invitation to become a candidate to be the president [of Princeton University] came out of the blue, but on reflection I could see how I ended up in that position — I had been taking more and more positions at the national level and within the university itself. Many scientists face choices that come once they are reasonably successful. Almost always there are invitations to be part of the leadership of the scientific community. For me that began with things like being on study sections, chairing scientific meetings, and being on national committees. As those invitations arrived on my desk and I began to judiciously accept a few of them, I realized two things — one is that I really enjoyed thinking about larger issues, and the other is that I discovered, quite frankly, that I was pretty good at it.

Q: After you arrived in Princeton in 1986, Bruce Alberts asked you to serve on the National Research Council committee assembled to study the feasibility of the Human Genome Project. You were the only woman and the youngest person on that committee. Why do you think Alberts approached you to be part of it?

A: I don’t want to put words in Bruce’s mouth given that he is a very dear friend of mine, but I suspected at the time that as they were putting that very distinguished group together, they looked at all the names and realized that there was not a single woman on it. So they went out specifically to find a woman. As I have thought about that experience, which has happened to me more than once, I have tried to balance two very different kinds of reactions. I could refuse the invitation because I did not want to be the token woman. The other reaction is to say, if I join this committee even when they are only putting me on it to keep the concentration of the X chromosome above 50%, and if I do well on that committee, it’s possible that the next time they put such a committee together, they will not be thinking “we better find a woman.” They will naturally be thinking of other women, so it will grease the path for women to be considered because of their qualities, not because of their gender.

Q: What was it like to be Princeton’s first woman president? Do you, in fact, want to be known as the first woman president of Princeton?

A: The second question is an easy question. I do not want to be remembered as the first woman president of Princeton. I served the institution long, and I hope that I will be remembered for the ways in which the university improved during my term as president. Regarding the first question — the fact that I was the first woman [president] was an issue for about six months both on campus and among the alumni body. About six months in, maybe even for some within a year, the fact that I was a woman was completely irrelevant, and everyone moved on. I certainly never thought of myself in that way. It was a short-term issue that dissipated quickly.

Q: What would you say are some of the key changes that still need to happen so that women feel more comfortable not only pursuing academic careers but also getting to leadership positions?

A: One of the most important advances in understanding why women have not advanced further has been the work on unconscious bias and stereotype threat conducted over the last 20 years in social psychology. When I was growing up and becoming a young scientist, some of the discrimination was absolutely overt. As hard as that was to combat, it was all out in the open. There was no political correctness at that time. People felt completely free to speak and behave in discriminatory ways. The challenge today is that while overt discrimination has been greatly suppressed, now we have to contend with something that is much more difficult — the unconscious bias. I recently read a paper published in Science that showed that little girls, sometime between the ages of 5 and 7, acquire the perception that brilliant means male. It is one of the most sobering articles that I have read in a very long time because it says that we have to start addressing this really early. Waiting until students arrive at university or until they get to graduate school is just too late. Unconscious biases — both the self-perception biases and the biases that are in society — are set well before. So I think the biggest challenge is learning how to confront these unconscious biases and figure out how to undo them.

Tilghman teaching a class

The other huge issue that we have not resolved in our society is how women manage work and family. In biology, the percentage of PhDs is now at parity, if not slightly biased in favor of females, but this statistic does not reflect what is happening when you look five, six, eight years later and ask what percentage of the newly hired faculty are women. That is such a critical period in a young woman’s life. It is a period when, if they are going to have families — and not everybody is, but if they are — that is the time they are thinking about it. The degree to which our workplaces make it hard to imagine combining a very successful scientific career with having a family is still a large barrier at that point in a woman’s career.

Q: Tell us more about the committee you appointed in 2009 to review undergraduate women’s leadership at Princeton. What has it achieved?

A: The most important finding that came out of that women’s leadership committee that was chaired by Nan Keohane, the former president of Duke and Wellesley, was the degree to which these incredibly bright freshman women arrive less self-confident than their male peers. And they leave Princeton less self-confident than their male peers. So we put in place programs to encourage self-confidence in young women.

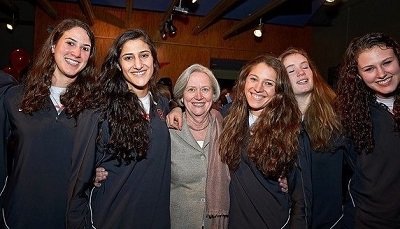

Tilghman with members of the Princeton University women’s basketball team

Q: What advice would you give to women scientists today?

A: I will give you a couple of pieces of advice that I have given to my own students in the past. Number one, when you are in training, focus. Identify the problem that you want to attack, focus on it, and do not get distracted. Graduate school and post-docs are not the times to be flitting from flower to flower. Number two, don’t let anybody turn you into a victim. One of the things I have seen over and over again is that once you get into a cycle of feeling sorry for yourself or feeling as though you’ve been discriminated against, it’s like going into a death spiral. So in a way, just put blinkers on and say “I’m ignoring all the signs from the outside that tell me that I don’t belong in this community or that I shouldn’t be here; I’m going to keep my head down and focus on my work, and I’m not going to let anybody distract me from my goal.” These are hard pieces of advice, but I think it is what most successful women did.

In terms of work-family balance, my most important piece of advice — and this is a hard one to do, but I think it is the key to everything — is to not feel guilty. Do not let guilt overwhelm you. I’ve seen so many women who are guilty when they are at work because they are not at home, and when they’re home, they’re guilty because they’re not at work, and guilt is another kind of death spiral. So just give yourself a break; be kind to yourself. Realize that there are only 24 hours in the day, there’s only one of you, you can only be in one place at a time, both of these aspects of your life are really important to you, and you are important to them, and enjoy both, and just toss guilt out the window.

Q: What are you proudest of in your scientific/administrative career?

A: When I was a scientist, what I felt most proud of was the success of my students and fellows, both while they were in my lab, and particularly when they went off on their own and became very successful scientists, and writers, and policy people, whatever they decided to do. I felt that the huge contribution I was making was to help mentor these students and fellows to successful careers. As president of Princeton, the thing I was most proud of was the quality of the team that I had assembled — their ability to work incredibly well together towards their common purpose to strengthen the university and make it a better place. I always felt that this was the most important thing I did as president.

Tilghman teaching with Professor Keith Wailoo