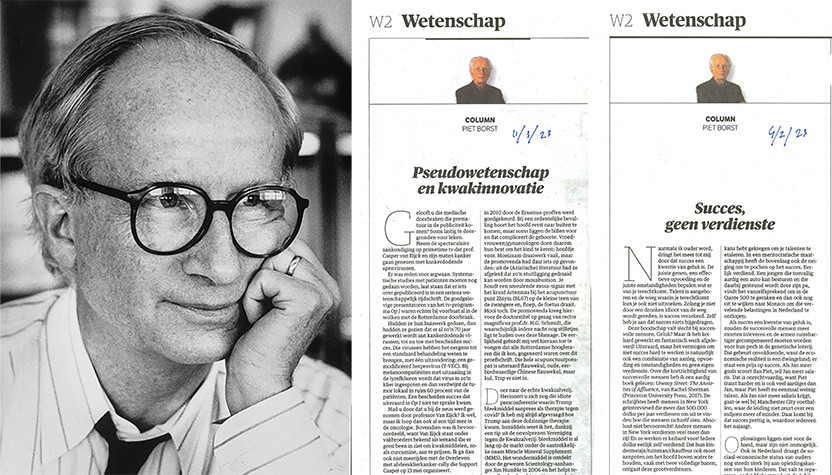

Piet Borst

Netherlands Cancer Institute

For an exceptional 50-year career of scientific discovery, mentorship, and leadership

The 2023 Lasker~Koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science honors a physician-scientist for an exceptional 50-year career of scientific discovery, mentorship, and leadership. Piet Borst (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam) boldly and repeatedly ventured into new territory in the laboratory, and he made seminal discoveries in multiple fields. His work revealed how parasites evade the human immune system, and it provided insights into the molecular pumps that underlie cancer drug resistance. He illuminated an unanticipated metabolic pathway, unveiled a novel DNA building block, and pinpointed the biochemical basis of an inherited disorder. With vision and fortitude, he shepherded the Netherlands Cancer Institute to world-class status. His contributions have extended far beyond his home establishments, as he has guided prominent scientific organizations and prize committees in Europe and beyond. He has trained scores of investigators who have gained international renown, and he has directed his passion for science and no-nonsense attitude toward educating the public as well.

The Secret to a Successful Career in Science—According to Magritte

There is no shortage of words of advice on how to become a successful scientist.

Award Presentation: Harold E. Varmus

Successful scientists make discoveries that reveal how the world works. Those discoveries sometimes improve the human condition and occasionally win Lasker Prizes. But a few great scientists are more than discoverers. They also have generous impulses to nurture discoveries by others; a history of extensive service to the scientific community; or a drive to learn and teach about the promise and perils of science.

Since 1994, the Lasker Foundation has awarded a biannual prize to such individuals, people who have made outstanding discoveries in the medical sciences, but have also displayed characteristics that inspire, in the prize’s memorable phrase, “deep feelings of awe and respect.” Today I have the pleasure of introducing you to Professor Piet Borst, who embodies those rare traits and is this year’s recipient of the Lasker-Koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science.

Piet’s qualities

Piet cuts a very large figure. He is a polymath of biomedical science, making waves in disparate fields: biochemistry, molecular biology, parasitology, and clinical genetics. He is renowned for his service to institutions, colleagues, trainees, and the public. And he is revered for the integrity, humor, loyalty, and frankness that are emblematic of his character. My job today is to summarize these awe-inspiring virtues.

Piet himself has attributed his success to good luck. Born with more than just a good brain, he was the son of a greatly admired academic physician in a place, The Netherlands, that has for centuries produced some of the world’s most prominent artists, philosophers, entrepreneurs, and scientists. Piet has spent nearly his entire life in Amsterdam, while influencing science globally. Despite his global reach, he has remained deeply and distinctly Dutch. But much more than his good luck or his essential “Dutchness” explain why the Lasker Jury has selected Piet for this award.

His Science

Piet’s accomplishments as a scientist are legion, a result of his insatiable curiosity, his fearless excursions into difficult domains of biomedicine, and his mastery and invention of many technologies.

When he enrolled as a student at the University of Amsterdam, his interests ranged broadly from literature and history to medicine. But when his clinical curriculum offered a break that permitted laboratory work, he took an unusual path. Bill Slater, a charismatic biochemist imported from Australia, persuaded Piet to characterize mitochondria in normal and cancerous mammalian cells. Although this ultimately revealed little about cancer, he solved a long-standing enigma about energy generation in mitochondria, discovering what is still sometimes called the “Borst shunt,” a pathway for electron transfer employing components of the sugar metabolic cycle. That success triggered his life-long fascination with mitochondria and other cellular organelles that tend to receive much less attention than the nucleus.

Yet, when another opportunity to get exposed to laboratory science arose after his time with Slater, Piet moved in yet another direction, learning molecular biology and virology with the Nobel Laureate Severo Ochoa—here in New York, at NYU—finding and characterizing the enzyme that duplicates the RNA genome of a bacterial virus.

After these successes, Piet was emboldened to abandon the idea of medical practice and accept an offer from Slater to join the biochemistry department at the University of Amsterdam, combining his new skills in nucleic acid research with his earlier interests in mitochondria.

His attention was soon drawn to trypanosomes—the single cell parasites that include the cause of sleeping sickness—because of their strangely configured mitochondrial DNA. So when he heard from George Cross, at Cambridge University, that trypanosomes can evade an immune attack by changing the major protein on their surface, he was ready to act.

To learn how the surface proteins varied, Piet and his trainees uncovered and explored several amazing phenomena: how surface protein genes move from many places in the parasite’s chromosomes to places near chromosomal ends (the telomers); how their messenger RNAs are spliced in an unexpected way; and how the short, repeated sequences at trypanosomal telomers, sequences that proved to be identical to human telomers, expand and shrink.

While this spectacular work was in progress, Piet moved his lab from the University to the Netherlands Cancer Institute, where he took on leadership responsibilities that I’ll describe in a moment. This change encouraged him to take up some form of cancer research, pursuing a new topic deliberately, rather than serendipitously. Soon—and without abandoning his beloved trypanosomes—he became well known for his work on novel proteins that can mediate resistance to cancer drugs and for discoveries of surprising things those proteins can do in normal tissues.

At about the same time, he and his students found, in trypanosomes and some other organisms, what few expected: a new component of DNA, adding new base—J— to the bases that everyone learns in high school—-A, C, G, and T. With tenacity, over many years, culminating just over a decade ago, Piet learned how that new base is made and how it affects cell behavior by terminating synthesis of RNA.

On top of all this, Piet had not forgotten clinical medicine. By determining the biochemical basis of two uncommon inherited diseases, Piet and his colleagues turned medical mysteries into solvable metabolic disorders.

His Service

As his prominence rose in medical science, Piet also became widely known for his enthusiastic service to science—-as a generous advisor to many institutions and funders and as an insightful leader of prize committees.

Like his father, he was also famous as a university teacher, sometime delivering more than a hundred lectures per year, energizing students about science, and bringing many undergraduates into his lab for their first exposures to research. Dutch scientists populate many of the leading research institutions around the world, and Piet is rightfully viewed as the father of the Dutch diaspora.

This extensive service pales, however, in comparison to two of Piet’s other accomplishments. In the early 1980’s he was persuaded become the Research Director of the Netherlands Cancer Institute (NKI), which, by many accounts, had become a sleepy, undistinguished institution. Within a very short time, Piet had used several strategies— recruiting talent astutely, encouraging changes in faculty behavior, and setting a personal example—to turn the organization into one of the world’s best centers for cancer research. On top of all this, for several decades, Piet wrote a column for one of Amsterdam’s leading newspapers, explaining and defending scientific work, challenging questionable medical practices, and urging public support for the scientific enterprise.

His Character

Much of what I have already said pays tribute to Piet’s character: his intellectual integrity, his passion for science, his loyalties to students and institutions. But you need to experience Piet’s personality at closer range to appreciate fully his droll humor, his intensity, and his frank—even blunt—views of so many things.

Consider one example: the advice that Piet delivered openly, a few years ago, to a colleague turning 80: “…the only jobs that will [now] come your way are the jobs that require wisdom, a euphemism for cognitive decline.”

Piet Borst is one of a kind. But I note, in closing, that there is at least one literary precedent— the lean, serious Clerk from Oxford, one of Chaucer’s pilgrims to Canterbury, a student of logic, who spoke…

“…with formality and reverence,

And short and quick and full of elevated meaning;

His speech was always consistent with moral virtue,

And gladly would he learn, and gladly teach.”

Thanks for listening and for honoring Piet Borst with your presence.

Acceptance remarks by Piet Borst

My path to science was a straight and obvious one. My mother was a smart dentist, who taught her six children the elementary Dutch virtues: swimming, ice skating, healthy ambition, and playing an instrument, in my case the cello. My father was an ideal role model, professor of internal medicine, charismatic physician and fanatic clinical researcher. The only downside of my youth was the Second World War. My father in a concentration camp; little food. In the winter of 1944-45, I ate sugarbeet remnants and tulip bulbs, not your standard Lasker lunch. It left no scars in me.

I had the privilege to get into science at the start of the golden age of biology. The fields in which I worked, mainly cancer and tropical diseases, have seen spectacular advances. When I started my PhD we knew so little about cancer that I spent 3 years to show that tumor mitochondria were not defective, in contrast to what the great Otto Warburg had postulated. Thanks to revolutionary advances in methods to study gene expression—and thanks to clever scientists—we now know what cancer is and how it arises. The Netherlands Cancer Institute even suggested in 2013 that 90% of all cancers would be cured or turned into a chronic condition with good quality of life within 25 years. This prediction was ridiculed in 2013, but I now think we may get there, given the recent advances in targeted therapy, immunotherapy and anti-cancer vaccination.

Knowledge of parasitic diseases, my other scientific interest, lags behind that of cancer, but I predict that this will not be the case forever. Whereas the differences between normal cells and cancer cells are small, the metabolism of parasites differs radically from that of our cells, providing ample opportunities for selective chemotherapy. The exotic and interesting biochemistry of parasites is going to be their downfall, eventually, and the basis for more Lasker prizes.

Whereas science has provided us with more powerful methods than ever to get at the truth, pseudo-science, conspiracy theories, and quackery flourish. I spent part of my life ridiculing all this nonsense in columns and interviews. However, at a time when Tony Fauci needs protection against death threats, and an American president uses prime time TV to promote bleach as a therapy for Covid, ridicule does not suffice. What then? Bruce Alberts has suggested the need to teach all kids the scientific method. I am in favor, but will that work for simple, not so smart people, bombarded by misleading information? Our challenge is to convince these people that science works, not only for us scientists, but also to solve their problems. I hope that Lasker prizes highlighting the power of science will contribute to that goal.