On a Tuesday morning in July 1984, Barry Marshall, a 32-year-old doctor at the Fremantle Hospital in Australia, asked his lab technician to fix him a stiff drink. The assistant obliged, scraping the contents of two petri dishes swarming with bacteria into a small beaker of beef broth. Marshall swallowed the murky brown liquid “quickly, like a shot,” he recalled.

He swigged that unappetizing brew to test a radical hypothesis. Five years before, his colleague J. Robin Warren, a pathologist at the Royal Perth Hospital, had noticed the corkscrew-shaped bacterium now known as Helicobacter pylori in tissue samples from patients with gastritis, an inflammation of the stomach lining. From their initial studies, Marshall and Warren were convinced that the bacterium caused ulcers and other gastrointestinal problems—a view almost no one else shared. To confirm those suspicions, the pair had to show that someone who came down with the bacterium later got sick. In the mid-1980s, antacids and diet could treat ulcers, but they often recurred and sometimes became serious enough to require surgery to remove part of the stomach. Marshall didn’t want to endanger anyone else by exposing them to the bug. “The only person in the world at that time who could make an informed consent about the risk of swallowing the Helicobacter was me,” he wrote.

Barry Marshall fulfilling Koch’s postulates

Courtesy of Abbott

He didn’t clear the experiment with his superiors at the hospital—or with his wife. But a couple of days after he drank the bacterial mixture, she and his mother noticed that something was wrong, reporting that his breath was “putrid.” Marshall soon began to feel bloated and unwell, vomiting every morning.

Ten days after downing the bacteria, Marshall underwent an endoscopy, in which a doctor threads a long tube down the esophagus, to remove a sample from his stomach lining. Under the microscope, the tissue was speckled with the twisty cells of H. pylori and showed telltale signs of infection, including an invasion of white blood cells. Marshall, who had been free of the bacterium before he drank the solution, did not develop an ulcer. He seemed to recover spontaneously but took a course of antibiotics to stamp out any remaining infection. But the experiment yielded “objective evidence that nobody could argue with,” Marshall said.

“That was really the turning point,” says J. Thomas Lamont, a gastroenterologist and emeritus professor of medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center who had no connection to the research. The discovery of H. pylori’s pathogenic powers upended the long-held medical wisdom that ulcers resulted from too much stomach acid, stress, or bad diet. “What Marshall came up with changed everything” for gastroenterologists and patients, Lamont says. For the first time, doctors could treat ulcers by fighting the bacterium that caused them—today’s standard therapy involves antibiotics and drugs to cut levels of stomach acid.

Marshall’s discoveries, which earned him the 1995 Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award and the 2005 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine (the latter shared with Warren), were important for another reason. Before Marshall began his research, doctors differentiated between infectious and chronic diseases, says Robert Gaynes, an infectious-disease physician and emeritus professor of medicine at Emory University. “That line began to blur” when Marshall showed that a microbe caused a chronic disease—ulcers, Gaynes says. Researchers have since found that microorganisms may trigger assorted chronic diseases, including arthritis, atherosclerosis, some cancers, and possibly Alzheimer’s disease. “It was an enormous paradigm shift,” Gaynes says.

Splendid Isolation

Marshall admits to being an unlikely medical revolutionary. He was born in 1951 in Kalgoorlie, a small mining town about 600 kilometers east of Perth. His father was an apprentice fitter and turner who later worked as a diesel mechanic and refrigeration engineer. His mother had been training to be a nurse but quit when after getting pregnant. The family lived intermittently in Kalgoorlie before moving to Perth when Marshall was 7 years old so that he and his siblings would have better educational and career opportunities.

As a kid, Marshall read everything he could, including his father’s technical books and his mother’s nursing texts. “I suppose I was born with boundless curiosity,” he recalled. Marshall extols his education in physics and chemistry at the Catholic school he attended in Perth, but he couldn’t take biology because the school was short on classrooms.

Barry Marshall working in his lab at the University of Western Australia in 2014

Courtesy of University of Western Australia

At the University of Western Australia in Perth, Marshall decided to study medicine because he thought he couldn’t handle the math required for his other main interest, electrical engineering. Finally, he could study biology. “I was in heaven,” he recalled. Marshall passed but didn’t stand out as a future Lasker and Nobel winner. He said he learned to economize on effort, allowing him to pursue other activities and spend time with his growing family—he was married and already had two children when finishing medical school in 1974.

After graduation, he couldn’t decide on a specialty. Continuing his medical training, he spent 6-month stints in rheumatology, oncology, hematology, and other specialties, liking them all. Each time, “I would come home and say, ‘This is it. This is what I want to be.” By the late 1970s, he was leaning toward cardiology and started work as a registrar—the Australian equivalent of a resident—at the Royal Perth Hospital, where he hoped to learn open-heart surgery.

His training required research experience. While searching for a project in 1981, he heard that Warren was looking for a partner to help investigate the unusual spiral bacterium in stomach biopsy samples. Marshall was intrigued because medical experts had declared that the stomach was too acidic for bacteria to survive. He and Warren agreed to collaborate, but his aspirations were modest. “Wouldn’t it be great,” Marshall thought, “if Robin let me be co-author [on a paper] and we described a new bacterium.”

Revolutionary Hypothesis

When the researchers began their investigation, the consensus was that excess production of stomach acid caused ulcers, often from stress. They could be serious—patients sometimes died from internal bleeding. The hot new treatments were drugs such as cimetidine (Tagamet) that diminished production of stomach acid. Though reducing ulcer symptoms, those drugs weren’t cures. Ulcers often came back if patients stopped taking the medication.

At first, Marshall and Warren weren’t sure what the spiral bacterium was doing in the stomach. To determine how common the bugs were, in 1982 the scientists analyzed biopsy samples from 100 patients who had undergone endoscopies. Seventy-seven percent of patients with stomach ulcers carried H. pylori, as did 55% of patients with gastritis and all patients with ulcers in the duodenum, the first section of the small intestine. Those high percentages suggested that the bacteria were up to no good, but only 13 patients in the study had duodenal ulcers. “Would gastroenterologists accept a revolutionary discovery . . . on the basis of 13 patients from Perth, Western Australia? It wasn’t going to happen,” Marshall wrote.

Barry Marshall (right) and Robin Warren teamed up in the early 1980s to probe some unusual bacteria that Warren had detected in stomach biopsy samples.

Courtesy of University of Western Australia

He was right. “Gastroenterologists didn’t believe a word of it,” Gaynes says. “He was ridiculed.” What Marshall described as his career’s most painful rejection showed how strong the skepticism was. In 1983, he and Warren applied to present a paper describing their work at a major gastroenterology conference in Australia. The organizers turned them down because reviewers had ranked their submission as one of the worst for that year, Marshall recalled. Even worse, the organizers wouldn’t let him present a poster, a less prominent way to deliver the results. Their message, he said, was that “we would be quite happy if you don’t come to the conference because it’s a bit shameful to produce research like this.”

Winning Over Skeptics

Marshall and Warren persuaded The Lancet, a world-renowned medical journal, to accept two of their papers describing the bacterium and suggesting its involvement in ulcers and gastritis. But they still hadn’t confirmed that H. pylori induced ulcers.

Most gastroenterologists doubted the bacterial hypothesis because the bug was already abundant in the general population, Lamont says. In some surveys, more than 80% of people were infected. “If I had found that an organism that might cause ulcers was found in 84% of the stomachs of my patients but also in most subjects without ulcers, I would have gone on to something else,” says Lamont, who was initially skeptical of Marshall and Warren’s claims.

But Marshall was certain that bacteria were the culprit in ulcers, continuing the research after he moved to Fremantle Hospital in a Perth suburb. To make the case, Marshall needed to show that infection with the bacterium led to ulcers. But when he gave H. pylori to guinea pigs, rabbits, and mice, the bacterium didn’t grow in their stomachs. He and colleagues then tried infecting piglets. To determine whether the animals hosted the bacterium, the researchers had to obtain stomach tissue samples. But the pigs grew too large for the endoscopes, designed for humans. Thus the experiment failed.

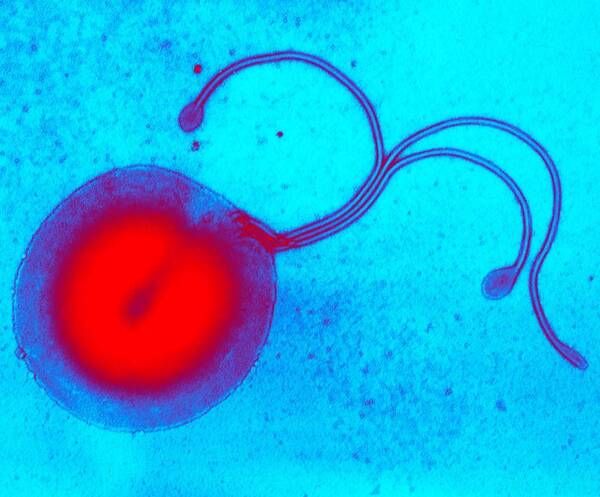

H. pylori, colored transmission electron micrograph (TEM)

This spherical or coccal form is not an active form, but a dormant one.

Courtesy of Biomedical Imaging Unit, Southampton General Hospital/ Science Source

Discouraged, Marshall “had no convincing data to prove the bacteria were indeed pathogens.” Without evidence, he couldn’t get funding for a clinical trial to test antibiotics as ulcer treatments. Out of options, Marshall decided to run the next experiment on himself. He had cured some ulcer patients with antibiotics and bismuth, an ingredient in Pepto Bismol. “I was fairly confident I could eradicate the bug” if he got very sick.

His unpleasant but brief illness after swallowing the bacterial solution led to further studies implicating H. pylori. In 1985, he and colleagues carried out a randomized clinical trial in which patients with duodenal ulcers took various combinations of antibiotics and bismuth. When the bacteria persisted, ulcers were about four times more likely to return than when the treatment had banished the microbes.

Marshall and Warren’s ideas caught on in Australia, where doctors started treating ulcers with antibiotics. But when Marshall took a job at the University of Virginia in 1986, he found that skepticism was rife in the United States. But evidence kept accumulating. In 1994, a National Institutes of Health conference made it official, concluding that patients with ulcers should receive antibacterial treatment.

Marshall continued to study H. pylori after moving to the United States and developed a breath test for the bacterium to spare patients the cost and discomfort of endoscopy. In 1996, he and his wife returned to Perth for a job at the University of Western Australia, where he remains.

Marshall overturned medical orthodoxy thanks to his tenacity, Gaynes says. “He stuck with it,” despite the doubting doctors and experimental setbacks. Moreover, Marshall had the crusade personality. He calls himself brash and had no reservations about challenging the medical establishment. “I never had any respect for authority,” he told one interviewer. Working in an isolated location also shielded Marshall from some criticism, Lamont says. “If he were in Boston, there would have been so much skepticism thrown at him by the elite professors.”

A sign of how important Marshall’s research was, Gaynes says, is that aspiring surgeons no longer learn how to perform ulcer surgery. “There’s almost no need for it.” Marshall didn’t just transform ulcer treatment. The updated research on H. pylori brought a second benefit, Lamont says: The bacterium also causes stomach cancer. Thanks largely to treatments that eliminate H. pylori, stomach cancer rates have declined globally. Marshall’s work, Lamont says, “had a huge impact.”

By Mitchell Leslie