On a sunny Sunday morning in 1975, two men hurried across a parking lot outside a hospital in Norwich in the United Kingdom, carrying a human liver in a plastic box. Transplant surgeon Roy Calne, of the University of Cambridge, and William Wall, a Canadian surgeon studying with him, had removed the organ from a donor and were rushing it to Cambridge, about 60 miles away, for transplantation into a critically ill patient. Reaching Wall's car, the pair set the box down to open the trunk. But the box slipped as they tried to lift it into the car. The liver and the ice keeping it cold tumbled out, recalls Wall, now an emeritus professor of surgery at Western University in Canada.

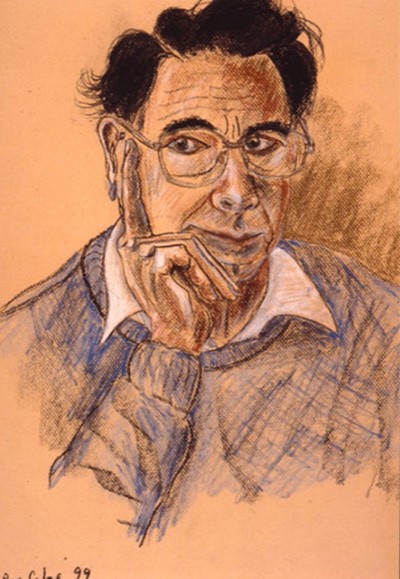

Calne: self-portrait (1999)

Courtesy of Sir Roy Calne

"I was horrified," Wall says. "I thought I was going to be sent home to Canada" because of the blunder. But Calne merely said, "My, my, my. Bill, the next time we might tape the lid of the box shut." The liver had landed on the ice and hadn't touched the ground or been contaminated. The two surgeons repacked it and later that day transplanted it into the patient. Wall says the incident shows one of Calne's most important qualities: "He never got perturbed about anything, even in the most dire circumstances."

Unflappability under pressure was one reason Calne excelled. He was one of the persistent pioneers who helped make organ transplantation, particularly liver transplantation, into a routine procedure that can extend patients' lives—often by decades. Calne and his US counterpart and rival Thomas Starzl "were the pillars of liver transplantation," says Carlos Esquivel, director of the adult and pediatric liver transplantation programs at Stanford University in California. For their achievements, the pair shared the Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award in 2012.

Calne transformed transplantation through his work in the operating room. "He is a very accomplished surgeon who was always pushing the boundaries," says transplant surgeon Julie Heimbach of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Calne's list of surgical firsts includes the first liver transplant in Europe; the first simultaneous heart, lung, and liver transplant; and the first cluster transplant, in which the patient received a new stomach, intestine, pancreas, liver, and kidney.

But equally important was his innovative research on thwarting rejection, a potentially fatal complication in which the recipient's immune system recognizes the transplanted organ as foreign tissue and attacks it. Calne identified the first immunosuppressive drug to curb rejection. His team later helped introduce cyclosporine, which was much more effective. "Cyclosporine turned transplantation from an experimental procedure into established clinical practice," says transplant immunologist Steven Sacks of King's College London in the UK.

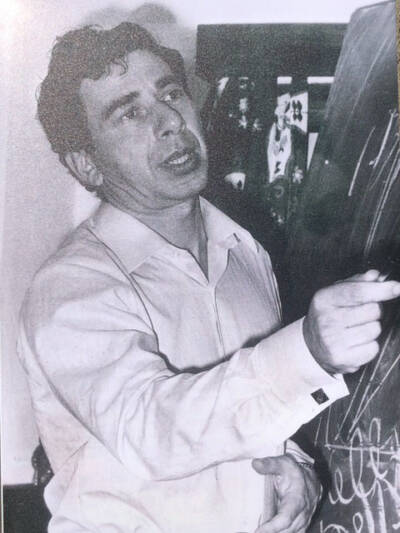

Calne at work on a painting from his Liver Transplant series (circa 1990)

Courtesy of Patsy Calne

When not performing surgery, Calne often sketched or painted. His works, which have been shown at exhibitions and used to illustrate books, often depict operations or his patients. Full of decisive brush strokes and bright colors, Calne's paintings reflect his personality, Wall says. "His art is bold, like him, but it shows the compassion he had for the individuals who were recovering from surgeries."

A Mechanic at Heart

Calne was born in London in 1930. His father owned a successful automobile repair shop, and the work there fascinated Calne. As he recalled in an interview, he enjoyed "taking mechanical things to pieces and putting them together again." But he also was intrigued by biology, creating a challenge when he tried to pick a profession. Should he become an auto mechanic or pursue medicine? To his mother's delight, by the age of 12 or 13 he had decided to become a surgeon. In a sense, Calne said, the choice merged his two interests. Like a mechanic, a surgeon has to worry about "how things work and what happens when they go wrong and whether you can put them together again."

In 1947, when Calne was only 16, he started medical school at Guy's Hospital in London, which he chose partly because it was a short train ride from his parents' house. Calne had a hard time fitting in with the other students, most of whom were about 10 years older and had fought in World War II. But he did well in the preparatory course and lab work and advanced to the next stage of the training, which involved looking after patients.

At the hospital, each trainee was tasked with one patient's care. The would-be doctors not only examined their patients but also shepherded them through treatments and even wheeled them to and from surgery. "You got to know the patients very well," Calne recalled. "If things went well . . . that was fine."

But things weren't going well for one of his patients, a young man dying from a disease that destroys the kidneys and had only two weeks to live. "That was a pretty awful shock for me," Calne said. Apart from the patient's failing kidneys, the man was in good physical condition, and Calne wondered why the hospital couldn't save him. He asked one of the senior doctors why they couldn't replace one of the man's kidneys.

The idea of swapping out a faltering organ, Calne once said, came from observing his father fix cars. "If the carburetor is broken, [you] put a new one in." In 1950, however, organ transplantation was science fiction—the first kidney transplant didn't take place for four more years. The senior doctor slapped down Calne's suggestion. Yet Calne and his fellow students couldn't see why replacing a kidney was impossible. Moreover, the doctor's attitude made Calne want to do it all the more.

Dealing with Rejection

For several years, he had to focus on other priorities, such as finishing medical school and his surgical training. Then in the late 1950s, while working as an anatomy demonstrator at Oxford University, Calne went to a lecture by eminent biologist Peter Medawar of University College London. Medawar had developed a technique for transplanting swatches of skin from one mouse to another without causing rejection. Yet despite his successful animal experiments, Medawar dismissed the idea of transplanting human organs. But the lecture galvanized Calne. "I wondered, 'Why couldn't we do something like that with kidneys?'"

Calne and his team looked for ways to tame rejection.

Courtesy of Patsy Calne

Before he could delve deeper into transplantation, though, he had to find a job. He didn't land any of the positions he had applied for at medical schools. "I was on the dole for a short time," he said. Calne caught a break when the Royal Free Hospital in London hired him. Even better, his supervisor endorsed his ambition to research transplantation.

By then, surgeons had performed more kidney transplants. Few patients survived very long, however, because doctors couldn't stem rejection. It had not been a problem for the first successful kidney transplant, accomplished by a team at Harvard Medical School in Massachusetts in 1954, because the donor and recipient were identical twins. To make transplantation useful for more patients, researchers had to figure out how to prevent the immune system from devastating the organs. One experimental strategy involved exposing kidney recipients to whole-body radiation, which suppresses the immune system. The result was disastrous. When the Harvard group used that approach, 11 of the first 12 patients died within a month of the surgery.

Looking for an alternative, Calne stumbled across a leukemia drug called 6-mercaptopurine that inhibited certain immune system responses in rabbits. Another scientist, Charles Zukoski of the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond, independently began experimenting with the drug around the same time. To test 6-mercaptopurine's effects, Calne gave the drug to dogs that had received kidney transplants. At the time, most other doctors and scientists remained skeptical about transplantation, and money for research was scarce. Calne was able to perform the experiment only because a colleague took out a loan to cover the costs.

The results, which Calne published in 1960, were worth it. The dogs lived longer after treatment with 6-mercaptopurine. Calne and Zukoski, who unveiled his findings about the same time, were the first scientists to show that a drug could quell organ rejection, at least temporarily. "It changed something that had been total failure to a partial success. Even Peter Medawar thought we were onto something," Calne recalled. He soon found that a chemical cousin of 6-mercaptopurine called azathioprine worked better. Then Starzl discovered that pairing azathioprine with steroids was more effective still. With that drug combination to fight rejection, in the 1960s a few hospitals began performing kidney transplants.

Transplanted to Cambridge

Calne scrambled to find work early in his career, but his research on rejection transformed his job prospects. After he taught at a couple of London hospitals in the early 1960s, the University of Cambridge hired him to chair its new surgery department. When he started the position in 1965, his secretary didn't even have a typewriter, and the department had only one other faculty member. "It wasn't a department, really; it was just a few people struggling to get hold of a typewriter for the poor secretary," he joked.

Calne spent the rest of his career at Cambridge, where he continued his work on transplantation. Now getting better results with kidneys, surgeons set their sights on another organ, the liver. But it is much harder to transplant for several reasons, Wall says. For one thing, the organ bleeds profusely, and curbing blood loss is a challenge. Removing the diseased liver also is demanding. And because the procedure involves clamping off major vessels that return blood to the heart, surgeons have to work quickly, Wall says.

Calne and Starzl had a friendly competition for decades.

In 1963, Starzl, then at the University of Colorado in Denver, became the first surgeon to try the operation, but the patient died during the procedure. Several more patients died during later attempts, prompting surgeons to halt liver transplantation until they could determine what was going wrong. After honing his skills by operating on pigs, Calne was convinced he was ready to replace a human liver. Starzl beat him to it, achieving the world's first successful liver transplant in 1967. Calne transplanted his first liver the next year—becoming the first European surgeon to do so—and he and colleagues set up a program in Cambridge to allow more patients to receive new livers.

Calne went on to carry out hundreds of the surgeries. In the operating room, he was a take-charge surgeon, says Chris Watson, a transplant surgeon also at Cambridge who trained with Calne in the 1980s. "He wanted to do the whole operation," from opening the patient's abdomen to stitching up the incisions, Watson says. Wall used the technique he learned from Calne during the roughly 800 transplants he performed over his career. "He was quick and very deliberate. He wasted no movements," Wall says. Because livers for transplantation had to be removed from donors and then delivered to Cambridge, the operations often took place late in the day, with music by Wagner playing, recalls Sacks, who also studied under Calne and assisted him during surgeries. "It was a tremendous spectacle."

Pittsburgh, Liver Transplant in Pittsburgh Medical School by Sir Roy Calne, 1992

Courtesy of Sir Roy Calne

As patients recovered from their operations, they might find themselves posing for paintings by Calne. He began painting as a child, and during his medical school years he often visited art galleries in London to copy well-known works. In his 50s, he began to pursue painting more seriously and started taking lessons. Advice from the Scottish painter John Bellany, who was one of his patients, "brought Calne's art to life," as one reviewer put it. For Calne, painting "was a way to relax and a way to get to know his patients better," Watson says. And Calne's surgical experiences afforded him deeper insights into their ordeals. As Bellany wrote in the catalog for a 1991 show of Calne's works, he "manages to delve under the surface, because he understands [his patients'] plight more than most of us."

"A Huge Breakthrough"

In the 1970s, Calne gave transplantation a second boost. Even with improved surgical techniques and decent drugs to rein in rejection, transplantation remained controversial. After a few hundred people received new hearts in the late 1960s, surgeons around the world stopped performing the operations for 10 years because patients died so rapidly. The results weren't much better for liver transplantation, Wall recalls. "Failures outnumbered successes by about 8 to 1, and very few patients left the hospital."

Rejection remained a major impediment. Calne and his team chanced on a better way to suppress immune attacks on the transplanted organ: the drug cyclosporine. Researchers with the Swiss drug company Sandoz discovered the compound and first investigated it as a treatment for fungal infections. But Calne and colleagues grasped its potential for transplant rejection and began testing it. After initial results in animals seemed "too good to be true," Calne asked the researcher in his lab who had performed the experiment to repeat it. The follow-up findings were just as impressive. Other groups of scientists also had zeroed in on cyclosporine. In 1978, Calne's team and those researchers published results showing that the drug was, in Calne's words, "a quantum improvement" over previous antirejection compounds. After the introduction of cyclosporine, the fraction of transplanted kidneys still working one year after the operation jumped from 50% to 80%.

Statistics like that helped break down the opposition to organ transplantation. As Calne noted in one of his papers, in 1977 only 22 liver transplant operations were done in Europe. In 1997, surgeons performed more than 3,600. About 9,000 patients now undergo the procedure every year in the U.S., and 95% are still alive after one year, Heimbach says. Although researchers have developed new drugs, cyclosporine remains a staple of regimens to prevent organ rejection.

Calne had boundless energy (shown here in a photo circa 1990).

Courtesy of Patsy Calne

Calne achieved so much, colleagues and other surgeons say, for several reasons. He had "boundless energy," Watson says. He could operate all night, see patients on the hospital wards the next morning, and then head to the tennis courts for a match. Another key quality was his daring, "that willingness to go beyond what had been done," Heimbach says. At the same time, he had the dedication to persevere even when things went wrong and patients died, she adds.

His competitiveness, exemplified by his relationship with Starzl, also drove him to succeed. "It was a friendly competition," says Esquivel, who studied under Starzl at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in the mid-1980s. "They had a lot of respect for each other." Still, whenever a new journal arrived in the mail, Calne would immediately check the contents to see whether Starzl had published a new article, Watson says. "They did spur each other on, and that was beneficial. It pushed the field along."

Calne, meanwhile, said that his "somewhat rebellious nature" also was important: "I've always tended to dislike being told that something can't be done."

By Mitchell Leslie