The lack of popes is mystifying when one considers that Picasso was fascinated by the work of his artistic forebears. He relentlessly copied, reconfigured, and transformed well-known paintings by the Old Masters. Three of the Old Masters who obsessed him — Raphael, Titian, and Velázquez — were themselves obsessed with painting popes. Picasso once proclaimed: “Any work they can do I can do better.” He also boasted: “When I was 4, I could draw like Raphael, but it has taken me a lifetime to paint like a child.” But could it be that Picasso met his match with the Vatican, realizing that when it came to painting popes, he could not outshine Raphael, Titian, and Velázquez?

Papal portraiture has a long tradition, and the story of how it has changed over the last 500 years mirrors how changes occur in the biomedical sciences. In both cases, breakthroughs in the field can be traced to the creative talents of a handful of individuals.

From Raphael to Titian

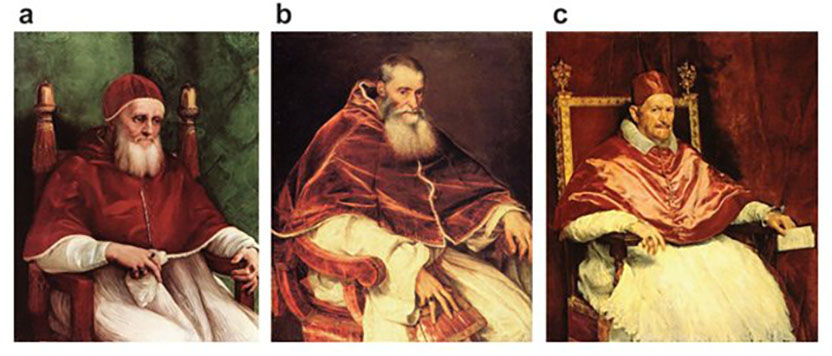

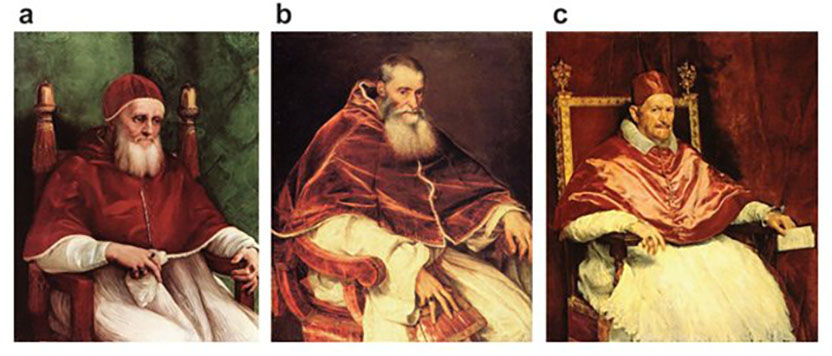

Before 1500, all papal portraits presented the pope either kneeling in prayer or in a narrative context together with his cardinals. In 1511, Raphael abruptly broke with tradition by depicting Pope Julius II in a moment of introspection sitting alone on an armchair, ensconced in his papal regalia consisting of crimson cap, crimson cape, white apron, and the Ring of the Fisherman, which is a solid gold bas relief of Saint Peter fishing from a boat (Fig. 1a). Raphael’s pioneering pose — the three-quarter view of the seated pope with his eyes looking down and his forearms resting on the papal throne — defined the style of papal portraits for centuries to come. In scientific parlance, Raphael’s contribution was the key breakthrough in the field of papal portraiture.

Since popes tend to be blessed with longevity, the next advance did not come until 35 years later, when Titian was summoned from Venice to Rome to paint Pope Paul III. Titian adopted Raphael’s general model in terms of pose and tenor, but departed from it in a radically original way. Titian used color and light to produce the lustre of the velvet, the stiffness of the linen, and the vigor of the flesh (Fig. 1b). The secret to Titian’s technical innovation was his use of a bare minimum number of hues — two in this case, red and white — applied in the subtlest of gradations.

Figure 1. Papal portraiture from Raphael to Titian to Velázquez. (a) Raphael. Pope Julius II. 1511. Oil on wood. 108 x 80.7 cm. National Gallery, London. (b) Titian, Pope Paul III. 1543. Oil on canvas. 106 x 85 cm. Museo Nazionale di Capondimonte, Naples. (c) Velázquez. Pope Innocent X. 1650. Oil on canvas. 114 x 119 cm. Palazzo Doria Pamphili, Rome.

From Titian to Velázquez

One hundred years after Titian’s masterpiece, the Spanish painter Velázquez journeyed to Rome, scrutinized Titian’s portrait of Paul III, and requested permission to paint Pope Innocent X. Innocent X was arguably the worst of all popes: he was hot-tempered, paranoid, ruthless, and unscrupulously duplicitous in taking the name of Innocent. What’s remarkable about Velázquez’s portrait is how he paints Innocent X in the Raphael-Titian tradition, thus satisfying his demanding client with a flattering portrait, yet at the same time conveying a hint of the pope’s explosive personality and corrupt character (Fig. 1c).

Contrasted with the calm enthronement of Titian’s Paul III, Velázquez’s Innocent X looks like he’s sitting on a powder keg ready to explode. Velázquez’s crimson tints are so marvelously orchestrated that one critic remarked: “If the Pope were to open his tightly clinched mouth, even his saliva would be blood red.” Joshua Reynolds, the influential 18th century English portrait painter, thought Velázquez’s Innocent X to be the finest painting he had ever seen.

Three versions of Pope Innocent X

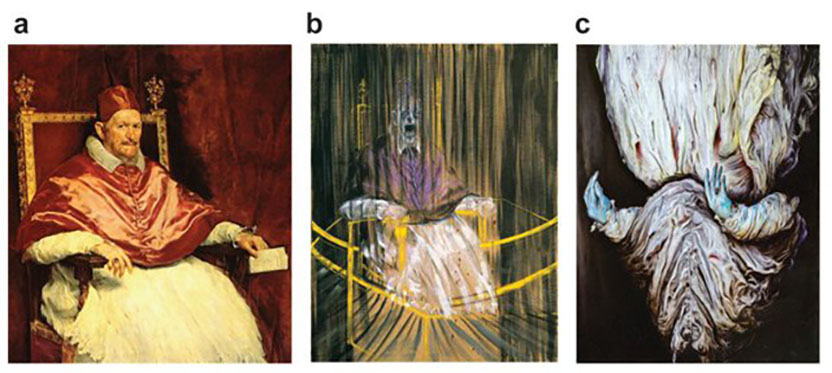

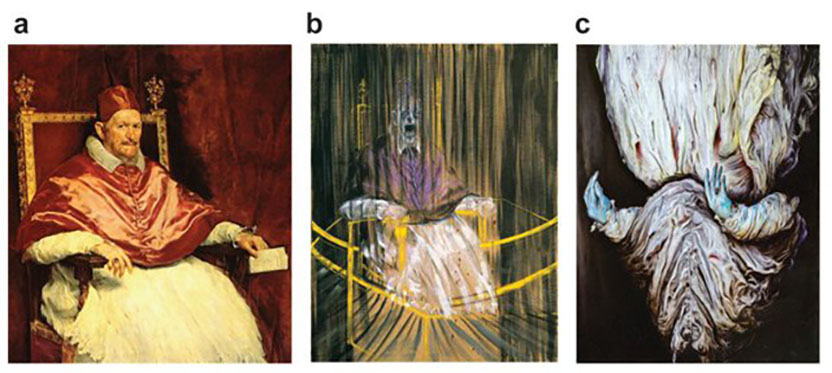

For the next 300 years, the field of papal iconography was bereft of innovation — both conceptually and technically. The Raphael-Titian-Velázquez model continued to hold sway over the field. Then, in 1953, the British artist Francis Bacon reinvented and reinterpreted Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X in a style appropriate for 20th century modern art (Fig. 2a,b). Bacon subverted the Pope by placing him on a throne that resembles an electric chair, cordoned off by a yellow hexagonal rail and encased in vertical lines that run up and down the picture like bars of a prison cell. Bacon dressed the pope in gaudy blood-stained attire and distorted his face with shattered glasses and a screaming mouth.

Figure 2. Three portrait versions of Pope Innocent X. (a) Velázquez. Pope Innocent X. 1650. Oil on canvas. 114 x 119 cm. Palazzo Doria Pamphili, Rome. (b) Francis Bacon. Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X. 1953. Oil on canvas. 153 x 118.1 cm. Nathan Emory Coffin Collaboration, Des Moines Art Centre. (c) Glenn Brown, Nausea. 2008. Oil on panel. 155 x 120 cm. Tate Liverpool.

Bacon detested authority figures. To vivify his aversion for ‘popishness’, he designed the screaming pope to shake people out of their traditional way of thinking and to touch them at their very core. In the world of science, this is precisely the type of work that Lasker Awards honor — work that screams out at us with new ideas and new ways of thinking.

And the latest new way of thinking about papal portraiture comes from an up-and-coming young British artist named Glenn Brown, who has perfected a novel technique for rendering the surface of a canvas as flat as and as smooth as a glossy magazine page. With this technique, Brown has created a stunning painting of Pope Innocent X that appropriates elements from both Velázquez and Bacon (Fig. 2c). Brown’s Pope was exhibited for the first time last year at a retrospective of his work at the Tate Gallery in Liverpool.

Brown distorts Pope Innocent’s image by removing his cape and cap, painting his hands gangrene green, and rotating his body 180 degrees. Only the white apron and the Ring of the Fisherman are retained. Brown literally turns the 500-year-old field of papal portraiture upside down and on its head.

After lunch, when you hear about the research accomplishments of this year’s Basic, Clinical, and Public Service Award recipients, you’ll see how they have turned the fields of nuclear reprogramming, cancer therapeutics, and health policy upside down and on their heads, transcending the Old Masters — the one thing Picasso never did.

More Jury Chair Essays