Max D. Cooper

Emory University School of Medicine

Jacques Miller

The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research

For their discovery of the two distinct classes of lymphocytes, B and T cells – a monumental achievement that provided the organizing principle of the adaptive immune system and launched the course of modern immunology

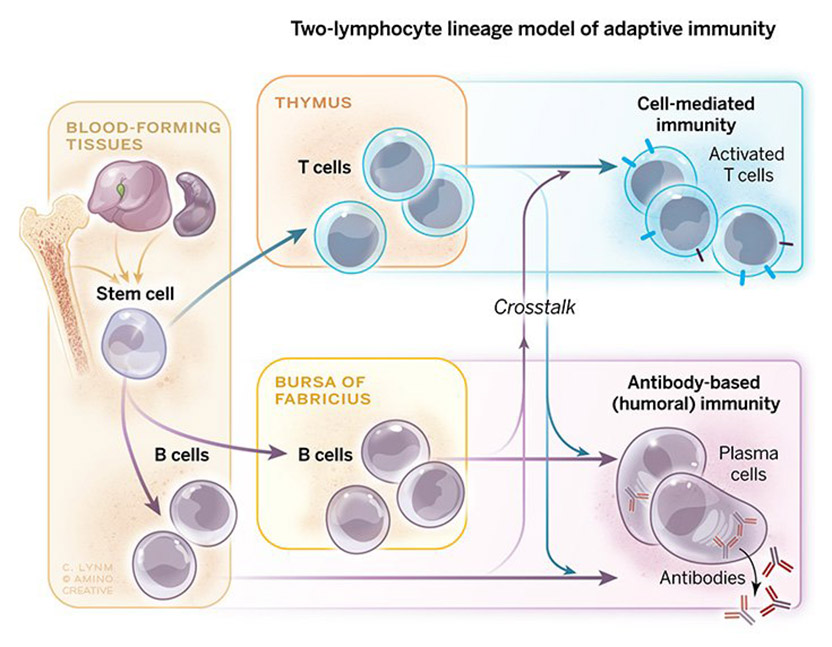

The 2019 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award honors two scientists for discoveries that have launched the course of modern immunology. Max D. Cooper (Emory University School of Medicine) and Jacques Miller (Emeritus, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research) identified two distinct classes of lymphocytes, B and T cells, a monumental achievement that provided the organizing principle of the adaptive immune system. This pioneering work has fueled a tremendous number of advances in basic and medical science, several of which have received previous recognition by Lasker Awards and Nobel Prizes, including those associated with monoclonal antibodies, generation of antibody diversity, MHC restriction for immune defense, antigen processing by dendritic cells, and checkpoint inhibition therapy for cancer.

When Miller began his research—around 1960—scientists had uncovered some features of the adaptive immune system, which protects our bodies from microbial invaders, underlies immunological memory, and distinguishes self from foreign tissue. They knew that antibodies, soluble proteins whose quantities surge after infection, perform jobs that differ from tasks that rely on live, intact cells such as rejection of transplanted grafts.

Seurat’s Dots: A Shot Heard ‘Round the Art World

How the color theories of a chemist have ricocheted across centuries of artistic and scientific imagination.

Award presentation by Craig Thompson

In this ongoing era of molecular biology, it is easy to forget that the functional unit on which biology is built, is the cell. Working independently, the two exceptional scientists that we honor today discovered that the adaptive immune system is composed of two distinct cell types, B cells and T cells. Through their studies of lymphocyte development, Max Cooper and Jacques Miller have provided the framework on which modern immunology is built.

Miller and Cooper’s combined discoveries have also provided the foundation for most of today’s immune therapies. Monoclonal antibody production would not be possible without the antibody repertoire created and stored within the B cell lineage. One such antibody will be recognized with today’s Clinical Lasker Prize. Similarly, the success of T cell-based therapies, such as the recent development of CAR-T cells to treat cancer, depend on the immunologic properties that T cells acquire as they undergo lineage-specific development in the thymus.

Acceptance remarks

Acceptance remarks, 2019 Lasker Awards Ceremony

I am truly honored to receive the Albert Lasker Award with Jacques Miller for our discovery of the T and B cell lineages and their pivotal roles in cellular and humoral immunity.

While growing up in rural Mississippi, nothing could have seemed more remote than a career in biomedical immunology. My first childhood encounters with cellular immunity came while fishing and exploring nearby streams; every summer I developed severe poison ivy, known now as a classic cellular immune reaction. My first memorable encounter with humoral immunity came from receiving rabies vaccination with painfully escalating inflammatory lesions that followed the 14 daily injections of rabies virus grown in rabbit brain. (This was well before Jeff Ravetch showed that this “Arthus phenomenon” was triggered by interaction between the constant regions of antibodies and their receptors.)

Ralph Platou, my pediatrics chief at Tulane, encouraged me to pursue an academic career and helped me obtain further training at the Hospital for Sick Children in London. A growing interest in congenital immune deficiencies and allergic diseases led to an immunology and allergy fellowship at University of California in San Francisco. My new mentor requested that on the way there I learn the immunofluorescence microscopy technique for use in studying cell-mediated immunity in a keratoconjunctivitis model. John Holborow, a British immunologist, agreed to teach me the immunofluorescence technique, but when I stated why I wished to learn it, he gently informed me that it was only useful for studying humoral immunity. Embarrassed by my naivety, I vowed if nothing else I would learn the difference between humoral and cell-mediated immunity.

A realistic opportunity to fulfill this vow came later in Minnesota, when I joined Robert Good’s research group soon after Jacques’s discovery of the critical role of the thymus in immune system development. Parenthetically, leading immunologists at the time were still vigorously debating whether antibodies were actually responsible for cell-mediated immunity.

My “eureka moment” was actually a “eureka week” as the results unfolded from our experiments coupling irradiation of newly hatched chicks with removal of their thymus or bursa of Fabricius. The complete elimination of B lineage cells and their antibody products in bursectomized and irradiated chicks, together with their restoration by non-irradiated bursal cells, clearly delineated the bursa-dependent differentiation pathway from the thymus-dependent pathway that is responsible primarily for cellular immunity.

The pieces of the puzzle provided by these results together with information derived from studies of immune system development in immunodeficient patients and thymectomized mice, alongside those of bone marrow stem cells, allowed us to draw a provisional map of how the T and B lymphocyte lineages are derived from hematopoietic stem cells.

Over the following decades this basic organizing principle has proven to be true for immune system development in all living vertebrate species. It has been extensively amplified and elucidated through the work of many immunologists to yield better understanding and treatment of a variety of diseases, prime examples of which we will hear more about today.

Acceptance remarks, 2019 Lasker Awards Ceremony

I am extremely humbled, honored and delighted to receive the 2019 Lasker Basic Medical Research Award and to share this prestigious award with my long-time colleague Max Cooper. We never worked together, but I have met him on many occasions and have read his published work with great interest. We have also shared both the 1990 Sandoz Prize for Immunology and the 2018 Japan Prize for Medicine and Medicinal Science.

My curiosity for how the body responds to infection began as a child. Although born in France, I spent part of my childhood in China and Switzerland, and escaped with my parents to Australia from China in 1941, because of the Japanese threat during World War II. That was the year my very beautiful eldest sister died from tuberculosis. She had contracted it at a boarding school in 1936 and, although my younger sister and I often played with her, even when she was coughing blood stained sputum, we never developed the disease. Her doctor was overheard stating to my mother that nothing was known about how the body resisted infection. That statement, and the fact that I grew up when World War II was raging in Europe and Asia, made me decide to study Medicine, and thereafter to be involved in Medical Research.

After my residency as an intern at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, Australia, I was awarded a Fellowship that enabled me in 1958 to study for a doctorate in London at the Cancer Research Institute. It was as a result of my studies on mouse lymphocytic leukemia, a cancer which in mice begins in the thymus before spreading elsewhere, that I made the serendipitous discovery of the immunological function of the thymus—a long-neglected organ. This stresses how important serendipity is in making really novel discoveries. A whole new world opened up before me and my work became more and more exciting, as happened subsequently during the identification of T and B cells, aided by my first PhD student Graham Mitchell at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne.

It is still now very exciting to me, to see that the thymus, once believed to be a useless vestigial organ, populated with cells which in 1963 were considered by Nobel Laureate Sir Peter Medawar “as an evolutionary accident of no very great significance”, is producing T cells involved essentially across the entire spectrum of tissue physiology and pathology. These cells act not just in reactions considered to be bona fide immunological, but also, to cite some examples, in metabolism, in tissue repair, in dysbiosis and in pregnancy. I also find it most rewarding to see that basic research on thymus function, first published in one of my papers in 1961, and on T and B cells a few years later, has sown the seeds that spawned the new era of immunotherapy which can now claim a seat in the therapeutic pantheon of oncology, next to and perhaps about to supersede surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Before I end, let me warmly thank the Lasker Foundation for celebrating basic medical research and for having chosen Max Cooper and myself for this prestigious award.