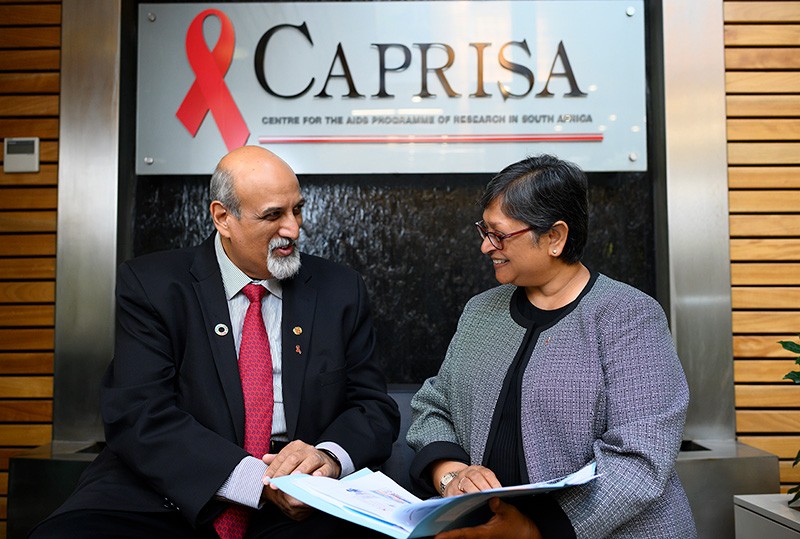

Quarraisha Abdool Karim

CAPRISA/Columbia University

Salim S. Abdool Karim

CAPRISA/Columbia University

For illuminating key drivers of heterosexual HIV transmission; introducing life-saving approaches to prevent and treat HIV; and statesmanship in public health policy and advocacy

The 2024 Lasker~Bloomberg Public Service Award honors Quarraisha and Salim S. Abdool Karim (CAPRISA and Columbia University), for illuminating key drivers of heterosexual HIV transmission and introducing life-saving approaches to prevent and treat HIV. The prize further recognizes them for their statesmanship in public health policy and their advocacy. The Abdool Karims have influenced AIDS programs across the globe and they have played pivotal roles in developing South Africa’s scientific capacity. Throughout their careers, they have championed science and its potential to benefit the world’s citizens.

Growing up under apartheid in South Africa, Quarraisha and Salim Abdool Karim gained a deep grasp of how societal inequities undermine health, education, and quality of life. Discrimination and segregation had limited their educational choices, and they recognized the broader effects as well. Drawn to correct wrongs, they have consistently juggled professional advancement with activism.

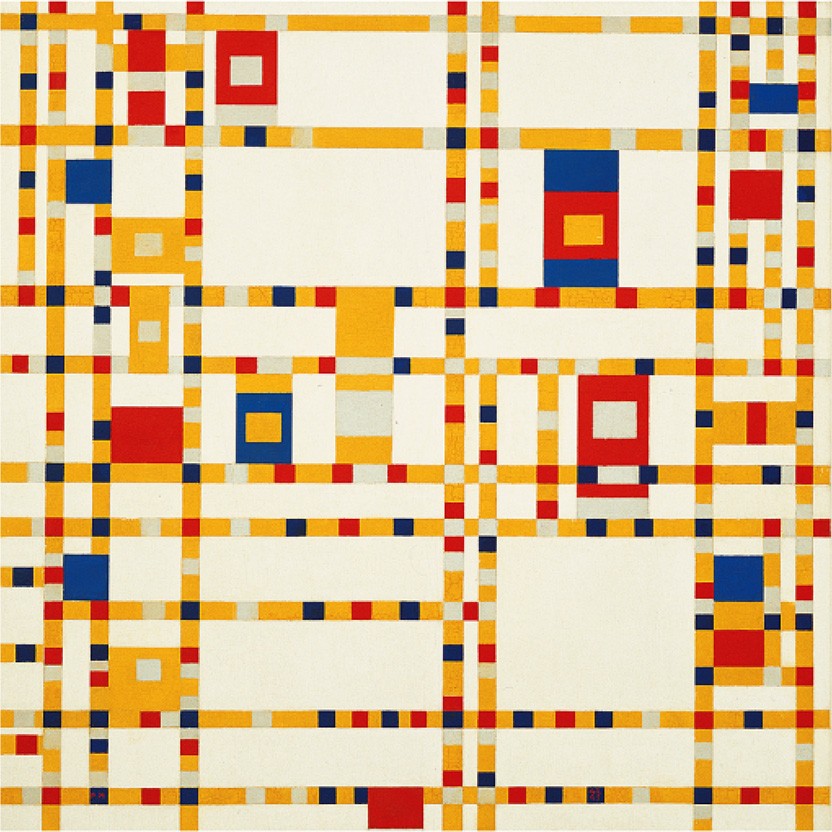

The boogie-woogie approach to creativity in art and science

The Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, famous for his geometric grid paintings, was an ardent jazz fan. In the late stage of his career, he became intrigued with boogie-woogie music, which inspired him to paint his masterpiece, Broadway Boogie Woogie.

Award presentation: Margaret Hamburg

Thank you Claire, for that warm introduction. It’s such a pleasure to be a part of the Lasker Foundation Family.

This year, I had the privilege of chairing the jury that selects the Lasker~Bloomberg Public Service award winner. It was a process that left me inspired by the incredible efforts underway around the world that are putting medical science to work for public health.

The Lasker~Bloomberg Public Service Award recognizes exceptional public health, policy, and advocacy initiatives that improve lives and advance the greater good. The award feels especially important at a time when we are asking a lot from anyone involved in medical research and public health endeavors. It’s no longer enough to just to be an expert in a particular area and achieve prominence in your field. We need you to be expert communicators, engaging with the public and politicians. We need you to be expert collaborators, building new partnerships and mentoring a new generation talent. We need you to be expert capacity builders, attracting investments for state-of-the-art laboratories and clinical trial networks.

This year’s winners, Quarraisha and Salim Abdool Karim, have embraced all these challenges. And their achievements in each area have been extraordinary. Their accomplishments are especially impressive because for more than 30 years they have worked as both professional partners and life partners. They have adjoining offices at CAPRISA—the Center for the AIDS Program of Research in South Africa. They share an administrative assistant. They even share a Twitter account. It’s hard to say whether they should co-author a book about their professional achievements or a guide to a successful marriage.

Let’s reflect for a moment on what this amazing couple has accomplished.

Their contributions to HIV prevention can in many respects be traced back to Quarraisha’s work in the early 1990s when she led South Africa’s initial efforts to understand community spread of HIV. It was a time when HIV prevalence was still relatively low in South Africa. She and her team found that infections were rising rapidly in teen-age girls. Her interest in developing new ways to prevent infections in women led to her a breakthrough collaboration with Salim.

In 2010, they reported evidence from a CAPRISA clinical trial showing that a vaginal gel containing the anti-retroviral drug tenofovir could prevent sexually acquired HIV. The study spurred one of the biggest breakthroughs of the HIV pandemic: the development of antiretrovirals as pre-exposure prophylaxis or PreP. The couple is now working on a long-acting version of PreP. They also are leading the development of an HIV monoclonal antibody. They want to determine if it offers another way to provide long-lasting protection while also informing efforts to develop an HIV vaccine.

Their ground-breaking work in the fight against HIV includes a major advance against a leading cause of death among HIV patients—co-infections with TB. They led a trial which showed that combining antiretroviral treatments with TB treatments greatly improves survival. This has now become a standard of care globally. In Africa, it’s credited with averting more than one hundred thousand deaths a year.

Few who knew of their work were surprised that the Abdool Karim’s were immediately front and center when the world was faced with a new pandemic: Covid-19. They were highly visible in mainstream media outlets in South Africa and across the region. They were effective communicators, pushing back against Covid falsehoods just as they had done earlier in their careers with HIV. In 2020, the John Maddox Prize for promoting sound science was split between two people: Anthony Fauci and Salim Abdool Karim.

The Abdool Karim’s also published studies examining how the new Covid virus affected HIV and TB patients. And their interest in Covid-19 variants provided the first evidence of the dangers posed by the omicron variant.

The couple is also leaving a lasting legacy of research capacity and talent. Twenty years ago, they led the creation of CAPRISA. It is now widely recognized as a global hub of innovation and discovery for HIV and other infectious diseases. They also created South Africa’s HIV Prevention and Vaccine Research Unit and Salim developed a biotech research center and a TB research institute in South Africa. Along the way, the couple has trained over 600 African infectious disease scientists. And they have been role models and inspirations to countless others.

Both are trained as infectious disease epidemiologists. Salim has said that he leans somewhat more to the laboratory side of things while Quarraisha may at times focus more on the role of human behavior in the spread of infectious diseases. He said they tend to meet together several times each day to discuss their research projects.

Salim uses a scientific term to describe how two people can be so successful as both colleagues and spouses. He said it comes down to chemistry.

There are more than a few true chemistry experts here today, but even for those of us with more rudimentary skills, I think we can all appreciate how when two or more chemical elements combine they form a compound. We are all fortunate that the very special, unique, and highly active chemical compound consisting of Quarraisha and Salim Abdool Karim emerged to save hundreds of thousands of lives, fight for scientific integrity and public trust, and build a new biomedical research infrastructure in South Africa that is now a major force for global health. They embody the Lasker’s Foundation commitment to generating support for medical research by recognition of scientific excellence, advocacy and education.

Thank you Quarraisha and Salim for your work. You are truly an inspiration for us all.

Acceptance remarks

Acceptance Remarks: Quarraisha Abdool Karim

Our lived experience of growing up in apartheid South Africa, has had a profound effect on how we see our role as scientists. As young anti-apartheid activists involved the daily struggle for freedom, human rights and justice, we know the importance of human dignity and inclusiveness in all facets of life including in our scientific endeavours. We also benefited from the wisdom and guidance of several mentors who were both great scientists and deeply committed anti-apartheid activists. We remain eternally grateful to them for their guidance and advice, which reinforced for us the notion that science in service of humanity and social justice are two sides of the same coin. In particular, we are grateful to President Nelson Mandela who shaped our perspective on the role of scientists in serving society, as he eloquently outlined in the Foreword he wrote in our book on AIDS.

It is therefore not surprising that our careers veered towards public health and that we have spent over three decades focusing on the health of the most disadvantaged in our society – young black women. Some 35 years ago, when the world’s attention was on HIV in men who have sex with men, we found that in Africa, young women bore the brunt of the HIV epidemic, largely due to sex with men who were about a decade older. And so, we focused our research on developing and testing technologies that empowered women to protect themselves. Our contributions to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis were one small but important step in the larger social challenge of gender-power dynamics, that highlights the powerful role that science can play in social transformation.

We are in a tumultuous moment globally—a time when science is needed more than ever to tackle several of the world’s most complex challenges—pandemics, climate change, man-made famines in the midst of conflicts and widening inequalities within and between countries. Our hope lies in the ubiquity of science, on it transcending political and cultural barriers as the universal language to build bridges between the peoples of this world. Our interconnectedness and shared vulnerabilities underscore the importance of working together as scientists in service of humanity to generate knowledge and innovations to make the world a better place for everyone.

In March 2021, the NIH announced a new program, CIPRA—Comprehensive International Program on AIDS—to create a small set of AIDS research centres of excellence globally. It was a marked departure from the usual NIH grants in that only non-US investigators and institutions could be leaders of the application. In response, Quarraisha and I brought together a group of 10 of South Africa’s leading medical scientists and so CAPRISA—the Centre for the AIDS Program of Research in South Africa—was born 22 years ago.

At that time, colonial-type relationships were the order of the day – where developing country researchers were reduced to being collectors of patients and samples for developed country scientists. CIPRA bucked that trend. It set out on a path of partnership, where there was no master and no servant, but rather partners working together for a common purpose and mutual benefit. CAPRISA itself was a similarly mutually beneficial cross-Atlantic partnership involving Columbia University and 4 South African research institutions—all as equal partners.

About a year after CIPRA, PEPFAR—the US President’s Emergency for AIDS Relief—was created as the biggest global solidarity initiative by a single country to address a health challenge. To save lives with treatment, PEPFAR served as a mechanism for the people of the US to assist poor countries with their AIDS response. A visionary humanitarian initiative, it took shared responsibility in a pandemic to new heights.

In accepting this Lasker award, we are recognising the power of global solidarity for global impact, which has been deeply imbued in our work on HIV prevention and treatment over the past 35 years. While we provided the initial evidence that antiretrovirals prevent sexual HIV transmission as PrEP, today PrEP is used in over 100 countries. If a patient with HIV and Tuberculosis co-infection anywhere in the world, including here in the US, is being treated according to WHO or CDC guidelines, that patient’s treatment is based on research conducted in South Africa by a multi-country CAPRISA team.

In a world wracked by division, conflict and anti-immigration hatred, this award is a sober reminder of how science reminds us of our shared humanity across the globe. We stand here today because of the power of global solidarity and partnerships in science that have saved tens of thousands of lives and helped make the world a better place for generations to come.