Richard O. Hynes

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Erkki Ruoslahti

Sanford Burnham Prebys

Timothy A. Springer

Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School

For discoveries concerning the integrins—key mediators of cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion in physiology and disease

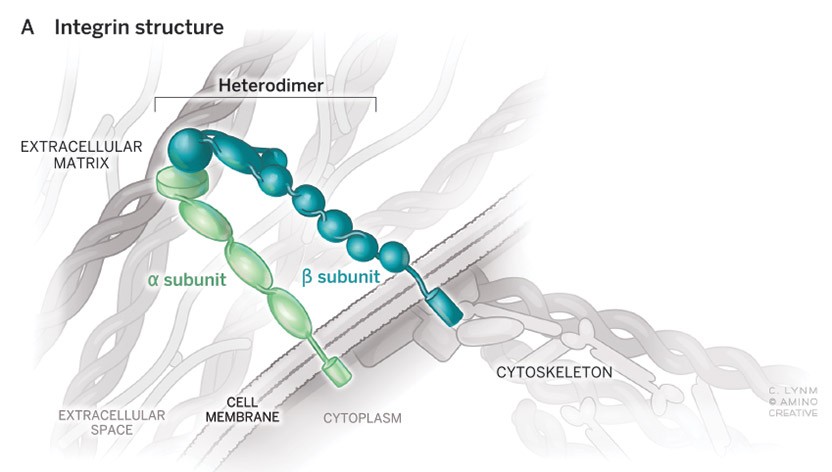

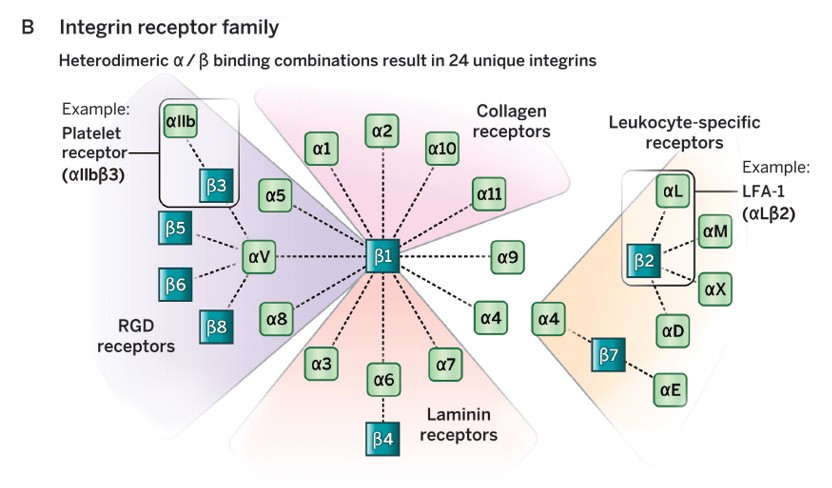

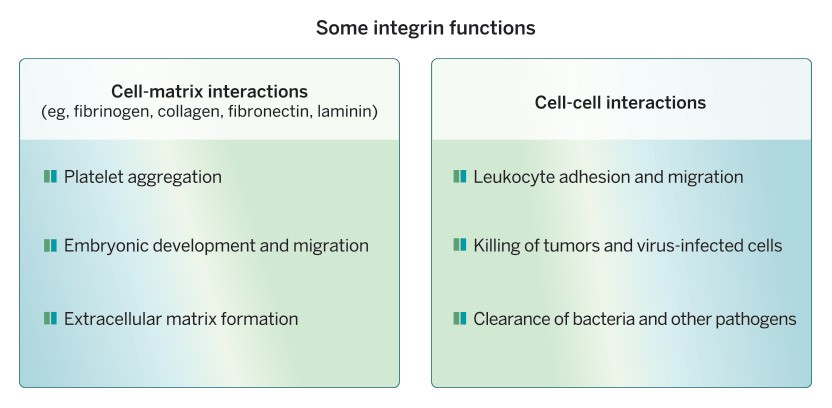

The 2022 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award honors three scientists for discoveries concerning the integrins, key mediators of cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion in physiology and disease. Independently, Richard O. Hynes (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and Erkki Ruoslahti (Sanford Burnham Prebys, La Jolla) identified a cell-surface-associated protein that helps affix cells to the surrounding material, the extracellular matrix (ECM). Then the researchers captured a receptor to which this protein binds. In seemingly unrelated studies, Timothy A. Springer (Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School) discovered transmembrane proteins that underlie the ability of immune cells to interact with their targets. These initially disparate lines of inquiry would converge and mushroom after the investigators realized that the proteins—now called integrins—belong to the same molecular family. Its members play central roles in an astounding array of processes in embryonic and fully formed organisms, and they offer intervention points for treating myriad diseases.

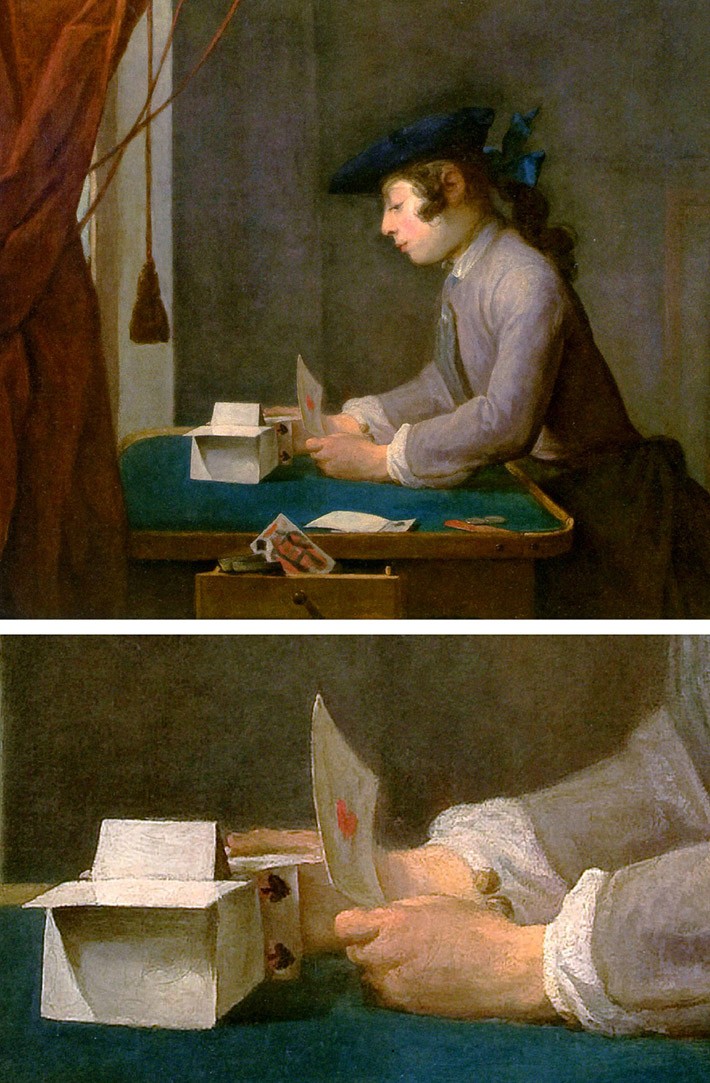

Building Castles in the Sky and Houses of Cards That Don’t Collapse

The creative process involves two phases—generating new ideas and then focusing on the most tractable and useful ones.

Acceptance remarks

Acceptance remarks, Richard Hynes

Both my parents had scientific backgrounds; I and my three siblings all became scientists, obviously influenced by this environment, and also in my case, aided by an excellent education in a Liverpool city high school and subsequently at Cambridge University Biochemistry in the heyday of the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in the 1960s. I then went to MIT Biology for my PhD; yet another wonderful place to learn how to do science.

I worked on developmental biology at MIT and it’s still one of my scientific loves. I then returned to the UK for a postdoctoral fellowship at the Imperial Cancer Research Fund in London and began to work on the cell biology of cancer. I owe a great deal to all those formative experiences that set me on the road to the research that led to the honour of this Lasker Award—how lucky can one be?

I and my laboratory members at MIT have spent the past 40-plus years exploring the mechanisms of how cells interact with each other and with the extracellular matrix, which is a complex meshwork of proteins to which most cells attach and upon and through which they migrate.

Cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion organize where cells are positioned in the body, who their neighbors are and how they interact with one another. Integrins are cell-surface receptors that control many of these interactions. They make connections to the extracellular matrix outside and to cytoskeletal machinery inside the cells and act as transducers of signals both into and out of the cells, key to their perception of, and impact upon, their surroundings.

When these connections are altered things can go awry, as in human genetic diseases that affect the adhesion of platelets or white blood cells, leading to various blood disorders, and in cancer when cells do not stay in their proper positions and metastasize to distant parts of the body. Metastasis and the roles of integrins and extracellular matrix proteins are our current areas of research interest—given my background, I think of metastasis as disorganized development.

This has been an exhilarating journey as modern biology has progressed over the past 50 years and powerful new methods of molecular cell biology have made possible experiments that we could not have imagined when we started on this road. The field of cell adhesion and integrins has been a very collegial and collaborative area in which to work. The open and friendly competition has contributed significantly to the scientific advances and will continue to do so in the hands of the many scientists now attracted to this field.

Clinical applications of our understanding of integrins are already having an impact and that will undoubtedly increase given their involvement in so many aspects of embryonic development, physiology and disease.

Acceptance remarks, Erkki Ruoslahti

I am from a small industrial town in southeastern Finland that shared a common border with the Soviet Union, and now with Russia. My father and older brother had engineering degrees from Helsinki Technical University. I decided to try something different and was accepted to study medicine at the University of Helsinki. My plans to become a practicing physician changed after my first year in medical school, when I took a summer job in a hospital bacteriology laboratory and got my first taste of research. This seemed interesting, and I asked if I could work on a research project. The head of the department took me under his wing. He was a great mentor, very keen on supporting young investigators. Several years later, after my postdoc fellowship, I rejoined the same department.

During my studies, we published a lot of papers on serum protein genetics and alpha-fetoprotein in cancer and fetal blood. Several of our papers came out in prominent journals, including Nature, and I thought I was doing quite well. Thinking of where to do a postdoc, I talked at a meeting to an Italian immunologist. He quickly became impatient when I told him about my work on serum protein genetics. He abruptly said, “why don’t you work on something important”—and got up and left. I wasn’t happy about how the interview ended, but having thought about it, I concluded that he had a point and tried keep the advice in mind in choosing projects to work on.

I did my postdoc at Caltech. Rubbing shoulders (and occasional playing tennis) with scientific giants such as Max Delbrück, Ray Owen, and others, was a heady experience for a young researcher from the far northern corner of Europe. At Caltech I was exposed to the ideas that led me to work on what became the recognition system composed of integrins and their ligands, such as fibronectin, in the extracellular matrix.

As my experience illustrates, graduate and/or postdoctoral projects often determine the direction of the rest of one’s scientific career. My advice to young researchers at the beginning of their careers is to think carefully when choosing a mentor and agreeing to work on a project. Ask yourself and older colleagues whose judgement you trust: Is this project worth working on? Will the results be potentially important? If the answer is not a clear yes, switch to do something else.

I am grateful for that long-ago comment about working on something important because it encouraged me to look for significant questions to study and undoubtedly contributed to my receiving this prestigious recognition.

Acceptance remarks, Timothy Springer

It is humbling and a great honor to accept the Lasker Award. I grew up in California with five siblings in a close family that took camping trips every summer. My dad inspired me as resourceful and adventurous. My mom loved and encouraged us. However, I floundered as a freshman at Yale. I studied too little and rebelled against the political establishment running the Vietnam War.

I wanted to do good but did not know how. I started by dropping out to join the Domestic Peace Corps. I served on a Shoshone Reservation in Nevada—living in a little cabin with no electricity, telephone, or running water. The nearest high school was thirty miles away. And in winter, a dirt road over a mountain pass made it impossible to get to. The Shoshones and I wanted to do something about it. So when the governor of Nevada held county road hearings, we made sure to show up and share what the kids in the community were going through. And within a year, that road was being paved.

After a year, I arrived as a transfer student at U.C. Berkeley. I majored in biochemistry and was inspired to learn about protein conformational change from Dan Koshland and protein chemistry from Jack Kirsch. With Jack Strominger, I earned a Ph.D. on biochemistry of cell surface proteins. By an amazing stroke of luck, I did a six-month postdoc in Cambridge England with César Milstein, who had just discovered monoclonal antibodies, for which he’d later win the Nobel Prize.

I then took a faculty position under Baruj Benacerraf at Harvard Medical School. Nothing at the time was known about the molecules that enabled cell-cell recognition in the immune system. I began to discover them by making antibodies that blocked cell-cell interactions, which led to the work I am being recognized for today.

About 40 years have passed since. I am blessed, because there was much to learn about integrin structure and function, and many of the mysteries of how integrins work are only being discovered today. This has required me to learn new techniques including structural biology and single molecule biophysics, and these challenges and the bright students and colleagues with whom I work keep me young. Out of the deep biology my colleagues and I have discovered, new drugs to treat patients have been approved and new companies have been founded. Although I have accepted the challenges of entrepreneurship and philanthropy, I am first and foremost a scientist, and discovery is still what I love most.