Roy Calne

University of Cambridge

Thomas E. Starzl

University of Pittsburgh

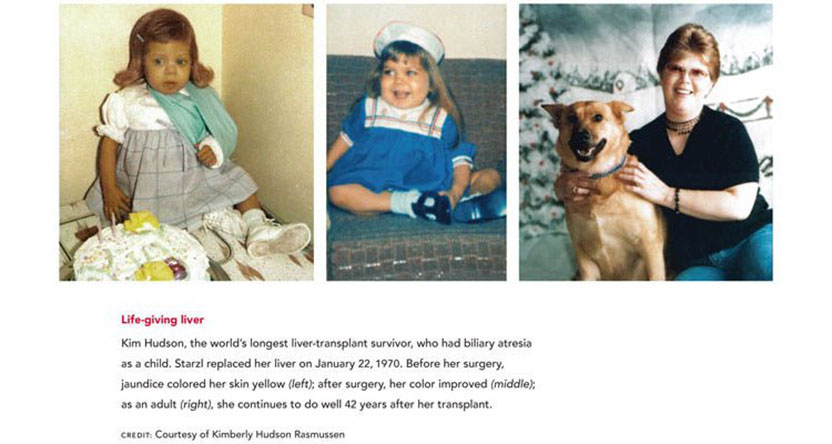

The 2012 Lasker~DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award honors two scientists who developed liver transplantation, an intervention that has restored normal life to thousands of patients with end-stage liver disease. Through their systematic and relentless efforts, Roy Y. Calne (Emeritus, University of Cambridge) and Thomas E. Starzl (University of Pittsburgh) created a medical procedure that most physicians deemed an impossible dream. Some of Starzl's and Calne's early patients — originally diagnosed with untreatable and lethal diseases — are still thriving today, decades after their surgeries.

The liver performs many services that are vital for life. It detoxifies harmful substances, manufactures essential materials for the body, stores energy, and secretes bile, which helps digest fats. In the late 1950s, serious liver diseases were fatal, and treatment prospects looked bleak. The idea of transplanting any organ from an unrelated individual seemed foolish to most experts. Rejection — the process in which a body's immune system attacks unfamiliar tissue — posed a seemingly insurmountable obstacle, and other aspects of liver biology presented overwhelming challenges. This organ supplies clotting factors, and liver disease produces tremendous pressure in the veins, creating a sea of wormlike vessels many times bigger than usual in which a tiny nick can trigger massive blood loss. Patients with liver disease, therefore, bleed extremely easily and often uncontrollably. Furthermore, multiple vessels deliver blood to the liver and drain other substances, so surgical manipulation of the organ is anatomically complicated.

Award presentation by Craig Thomson

The best in human achievement is often brought out when there are two closely matched rivals, competitors who bring out the best in each other as they strive to succeed. In sports, a number of such historic rivalries come to mind: Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris in baseball, Larry Bird and Magic Johnson in basketball, Mohammed Ali and Joe Frazier in boxing.

The best in human achievement is often brought out when there are two closely matched rivals, competitors who bring out the best in each other as they strive to succeed. In sports, a number of such historic rivalries come to mind: Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris in baseball, Larry Bird and Magic Johnson in basketball, Mohammed Ali and Joe Frazier in boxing.

Today, we honor two physicians who pushed each other to achieve something believed by the medical profession to be impossible. Their rivalry has been just as compelling and competitive as any sports duo, but their combined achievements will have a much more lasting impact.

Acceptance remarks

Acceptance remarks, 2012 Lasker Awards Ceremony

As a medical student in 1950, one of my patients was a boy of my age dying of kidney failure and I was instructed to make him comfortable, for he would be dead in two weeks. I asked if he could have a graft of a kidney, and I was told "no," and then when I asked "why," the subject was dismissed with the words "it can't be done." A few years later, Dr. Joseph Murray demonstrated that it could be done with the successful transplantation of a kidney between identical twins. For those who did not have an identical twin, graft rejection would interfere with development of this clinical field, and I started to investigate kidney graft survival in experimental animals in the United Kingdom with total-body X-irradiation, which failed miserably. I decided to use anti-leukemia drugs and was fortunate in achieving prolongation of kidney grafts survival in animals treated with 6-mercaptopurine.

I was awarded a Harkness Fellowship at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Dr. Francis Moore's department and the laboratory of Dr. Joseph Murray. On my way to Boston, I met Drs. Hitchings and Elion, who had synthesized 6-mercaptopurine, and asked them if they had anything better. They gave me some compounds, one of which was azathioprine, which proved to be a little better than 6-mercaptopurine and, when used in the clinic with steroids, was the start of clinical organ transplantation between individuals who were not twins.

On returning to the United Kingdom, I started a program of kidney transplantation and also experimental liver grafting and found, unexpectedly, that pig liver transplants were sometimes not rejected. This 'liver tolerance' was a fascinating subject immunologically, and the mechanism has still not been fully determined.

Jean Borel described the immunosuppressive effects of cyclosporine, but the Sandoz company felt it was not worth pursuing. The results we obtained with cyclosporine on organ grafts were better than any other immunosuppressive regimen. With some difficulty, I persuaded Sandoz to produce the compound in sufficient amount to investigate in the clinic. Unexpected nephrotoxicity was observed, but when the dosage was carefully adjusted, cyclosporine changed the one-year functional survival of kidney grafts from 50% to 80%. This was a watershed in organ transplantation; prior to this, approximately ten centers in the world were seriously involved. Within two years after the introduction of cyclosporine to the clinic, there were more than 1000.

I started the clinical liver transplant program in Cambridge in 1968 and had frequent contacts with Dr. Starzl so that we could learn from each other's experience and try to avoid making the same mistakes.

In Cambridge, we developed rapamycin, which proved to be an effective immunosuppressant but had a completely different mode of action to the calcinurine inhibitors and on its own had little or no nephrotoxicity.

Using the powerful monoclonal antibody produced by Waldmann's group in Cambridge, campath-1H, we started a program of preemptive induction with the antibody at the time of operation and then minimal maintenance drug dosage, half of one drug instead of full dose of three. This we called "almost" or "prope tolerance."

We can expect continuing advances, but also it is necessary to address the ethical dilemmas raised by transplantation where the generosity and charity of the donor must not be abused due to the shortage of organ donors.

The priceless reward for successful liver transplantation has been the outstanding quality of life that many of the patients have achieved. My longest survivor at 38 years has recently completed a 150-mile hill cycle ride. I found that painting some of my patients enabled me to establish personal friendships and, with children, drove away the fear of a doctor in a white coat.

Acceptance remarks, 2012 Lasker Awards Ceremony

Thank you for this award — and for the bonus of a reunion with my old and deserving friend, Roy Calne. When we arrived on the scene 50 years ago, patients dying from end-stage kidney, liver, or other vital organ diseases could be offered little more than priestly comfort.

The thrilling concept of organ replacement that then began to take shape was a beacon of hope. However, the technology could not be efficiently applied until rejection could be reliably controlled.

Once that was accomplished, all decisions in the care of patients with failure of a vital organ would have to take into account the possibility of transplantation. Nowhere was this more clear than with end-stage hepatic diseases for which transplantation up to the present day is the only option.

As transplantation of different kinds of organs was accomplished, thoughts turned back to what might have been. How much more complete would the world have been if Mozart could have received a kidney transplant instead of dying of glomerulonephritis at the age of 35? A generation later, Beethoven died of liver disease. Or closer to home, what might have become of our friend turned blue by heart disease, who stopped coming to classes one day and never was seen again?

Transplantation has not previously been acknowledged by a Lasker prize. One reason could be the difficulty of determining who should get it. Transplantation services are not provided by single individuals. The team is what counts, and it is on behalf of my research and clinical teams — first in Denver and then in Pittsburgh — that I accept this prize.

And by the way, the prize could have gone to one of those courageous kidney, liver, or heart recipients who faced the great unknown in the early years and chose to run the uncharted gauntlet of transplantation instead of giving up. Win or lose, these were the heroes. Some of the winners are in this room today.

Very few people have been privileged to see their grand illusion mature into reality. Sir Roy Calne and I were amongst those exceptions, beginning a half-century ago. That means, of course, that we are just about the oldest people in this room today. The fine lunch and all that goes with it are cherished rewards.

Interview with Roy Calne and Thomas E. Starzl

Video Credit: Susan Hadary