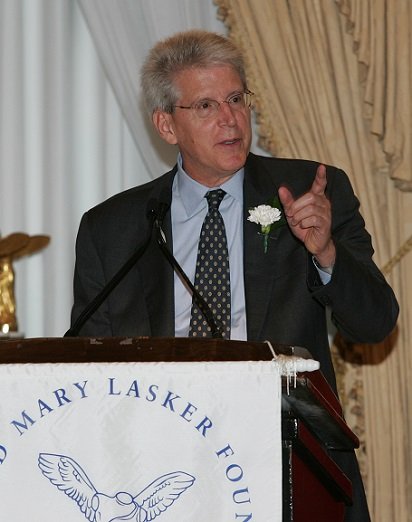

Matthew Meselson

Harvard University

For a lifetime career that combines penetrating discovery in molecular biology with creative leadership in public policy aimed at eliminating chemical and biological weapons.

The 2004 Albert Lasker Award for Special Achievement in Medical Science honors a researcher who has made world-class contributions to two different aspects of the scientific enterprise: molecular biology and public policy. Matthew Meselson has deciphered fundamental biological problems and has helped to prevent the manufacture and spread of biological and chemical weapons.

In 1958, Meselson (then a graduate student of Linus Pauling at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena) and Franklin Stahl showed that DNA duplication produces two identical daughter molecules, each containing one parental and one newly formed strand. This work provided compelling support for Watson and Crick’s proposed mechanism of DNA replication and for their double-stranded helical model of DNA. To perform this experiment, Meselson and Stahl first grew bacteria in broth that contained heavy nitrogen and then switched the microbes to broth that contained light nitrogen. Because the cells incorporate nitrogen into DNA, this scheme allowed the scientists to distinguish between old (heavy) and new (light) strands. To analyze the DNA generated during the experiment, Meselson invented a technique called equilibrium density gradient centrifugation, which allowed him to distinguish between DNA molecules that differed slightly in density. In this way, he and Stahl showed that a parental helix made of two heavy strands duplicates to give two molecules, each composed of one heavy and one light strand.

Award presentation by Thomas Maniatis

I am honored to introduce Professor Matthew Meselson, the recipient of the 2004 Albert Lasker Award for Special Achievement in Medical Science. Matt was the mentor of Mark Ptashne, a Lasker Award winner in 1997, who was my mentor. Matt is therefore my scientific grandfather. I have known Matt for over 30 years, and have marveled at his ability to remain at the forefront of science and at the same time serve his country as an advisor at the highest levels of government. His secret is simple — he is incredibly smart. Matt is being recognized for his extraordinary contributions to two different areas of the scientific enterprise: molecular biology and public policy.

I am honored to introduce Professor Matthew Meselson, the recipient of the 2004 Albert Lasker Award for Special Achievement in Medical Science. Matt was the mentor of Mark Ptashne, a Lasker Award winner in 1997, who was my mentor. Matt is therefore my scientific grandfather. I have known Matt for over 30 years, and have marveled at his ability to remain at the forefront of science and at the same time serve his country as an advisor at the highest levels of government. His secret is simple — he is incredibly smart. Matt is being recognized for his extraordinary contributions to two different areas of the scientific enterprise: molecular biology and public policy.

In 1958, as a graduate student at Caltech, Meselson conceived the theoretical basis of a technique called equilibrium density gradient centrifugation, and showed that this method could be used to separate macromolecules that differ only slightly in their densities. He and Franklin Stahl then used the method to address the question of how DNA replicates. They designed an experiment so elegant and so decisive it became known as the most beautiful experiment in biology. They showed that DNA duplication produces two identical daughter molecules, each containing one parental and one newly formed strand. This work provided compelling support for Watson and Crick’s proposed mechanism of DNA replication and for their double-stranded helical model of DNA.

Acceptance remarks by Matthew Meselson

Acceptance remarks, 2004 Lasker Awards Ceremony

Many scientists became intrigued with science while still quite young. For me, as a schoolboy in Southern California, it was chemistry and the thought that perhaps chemistry and physics could eventually explain how living things replicate themselves. Except for the guiding framework of classical genetics and some general insights from structural chemistry, the subject was then almost totally mysterious.

In 1953, I was accepted into a graduate program at the University of Chicago called “Mathematical Biophysics.” These were attractive key words to a young person wanting to apply chemistry and physics to biology before DNA had set the agenda. Intending to leave for Chicago, I was invited to a swimming pool party at the Pauling house in Sierra Madre. Linus, whose course in General Chemistry I had taken as a Caltech undergraduate, came out of his study, looked down at me in the water and said, “Well, Matt, what will you do next year?” Hearing my plan, his response was, “But that’s a lot of baloney. Why don’t you come be my graduate student?” Of course, that’s what I did.