Two art works discussed in this essay — a painting at the Royal Academy and a sculpture at the Louvre — exemplify two different routes to achieving artistic greatness: one involving creation and the other involving revelation. As in art, creation (through invention) and revelation (through discovery) are two different routes to advancement in the biomedical sciences.

Two art works discussed in this essay — a painting at the Royal Academy and a sculpture at the Louvre — exemplify two different routes to achieving artistic greatness: one involving creation and the other involving revelation. As in art, creation (through invention) and revelation (through discovery) are two different routes to advancement in the biomedical sciences.

Creation and revelation: Two different routes to advancement in the biomedical sciences

This past summer, two of the world's great art institutions — the Royal Academy of Arts in London and The Louvre in Paris — held exhibitions in which the highlight was the depiction of a tree. Artists have long been fascinated with trees, which are Nature's only living elements that link Heaven, Earth, and the Underworld. The tree at the Royal Academy — a painting — and the tree at The Louvre — a sculpture — exemplify two different routes to artistic greatness — one involving creation and the other revelation.

As in art, creation (through invention) and revelation (through discovery) can serve as two different routes to advancement in the biomedical sciences. The words 'creation' and 'revelation' are usually uttered at Bible classes rather than at Lasker luncheons. But, as you'll hear in a moment, this year's Lasker Clinical Award (for the invention of prosthetic cardiac valves) is an example of advancement through creation; the Basic Award (for the discovery of the immune system's dendritic cells) exemplifies advancement through revelation; and the Public Service Award recognizes a lifelong career devoted to both creativity and discovery.

Creating a tree at the Royal Academy of Arts

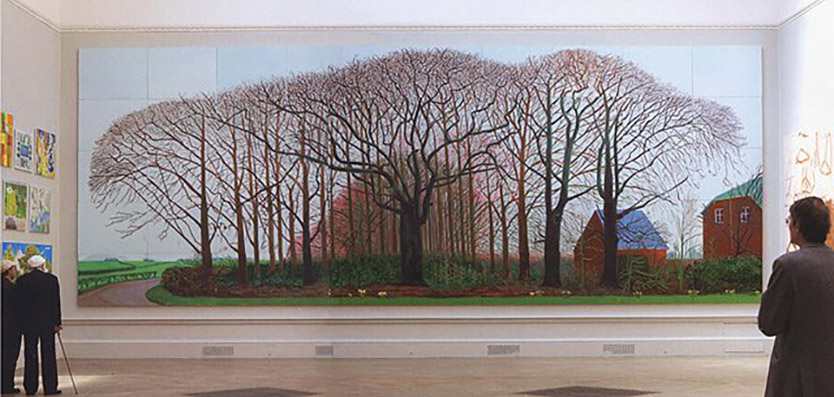

The tree at London's Royal Academy was the centerpiece of a painting by the Los Angeles-based British artist David Hockney. Hockney's painting is a massive mural, measuring 40 feet wide by 15 feet high (Fig. 1). In size, it is a close second to the largest oil painting ever done, Tintoretto's Paradiso in the Doge's Palace in Venice. Hockney's painting depicts an ordinary English countryside with a gigantic sycamore and its immense complex network of spreading and intertwining branches. The painting is so enormous that it literally engulfs the viewer in a way that one feels like one is actually standing in front of a real tree.

Figure 1. Bigger Trees Near Water. 2007. Oil on 50 canvases, 15×40 feet overall. David Hockney's creation of a tree fills a whole wall in the largest gallery at London's Royal Academy of Arts. The man at the left with the walking cane is Hockney himself. The painting was on display at the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition in London, 11 June–19 August 2007.

Hockney's biggest hurdle in executing this on-the-spot landscape was to overcome the difficulty of stepping back so as to view what he was doing in one part of the work in order to relate it to another part. He solved this perspective problem by an inventive computer-tracking method involving digital photography. This allowed him to paint 50 identically-sized smaller canvases that were then assembled into the final mural. Once Hockney conceived his strategy, he and one assistant completed the painting in a three-week sprint — a tour de force of artistic invention and creation.

Revealing a tree at the Louvre

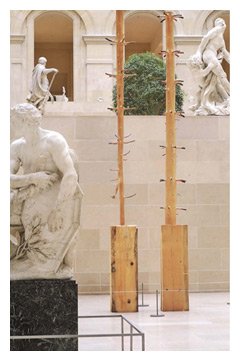

The tree at the Louvre was a sculpture by the Italian artist, Giuseppe Penone — a leading conceptual artist who focuses on elements derived from nature. The Louvre invited Penone to select one of his contemporary sculptures that would engage in a dialogue with the monumental 18th century French garden statuary in the courtyard of the Richelieu wing of the Louvre.

Figure 2. The 10-meter Tree. 1989. Wood. Tree 1, 16.5 x 1.5 x 1.6 feet; tree 2, 16.5 x 1.5 x 1.6 feet. Giuseppe Penone's revelation of a tree is shown in the Cour Puget courtyard of the Louvre, in juxtaposition with the gallery's 18th century French garden statuary. The sculpture was on display at the Louvre's Counterpoint III exhibition in Paris, 5 April–25 June 2007.

Penone's tree is a single 10-meter timber beam that was cut in half and presented in two parts, each 16 feet high (Fig. 2). After removing the bark from the two beams, Penone used a chainsaw and a chisel to peel away the internal rings of growth, after which he meticulously worked around the knots to reveal the heart and soul of the tree, i.e. the internal structure of its narrow core and developing branches. The beams at each end were left untouched, providing natural pedestals for the two side-by-side sculptures. When juxtaposed against the voluptuous marble statuary in The Louvre, Penone's 10-meter Tree is a work of great purity and spectacular elegance.

In the same way that Michelangelo chiseled out and revealed the statue of David that preexisted in his block of Carrara marble, Penone discovered and revealed The 10-meter Tree by taking matter away from his block of timber. This 'revelation' technique of removing matter is a fundamentally different approach to art than the 'creation' approach of Hockney, who produced a tree by adding matter to his 50 canvases.

After lunch, our Awards presentations will proceed in reverse Biblical order. I'll begin with a story of revelation and discovery, telling you about this year's Basic Science Award. Mike Brown will then tell you about the Clinical Award, an example of creation and invention. And the last presentation will be made by Harvey Fineberg, who will tell you about the Public Service Award — the Big Bang of the day.