Lasker Jury Chair Joseph Goldstein writes about the essence of creativity making parallels between art and science. He begins by quoting Oscar Wilde who has famously proclaimed that the most creative individuals are those who have taught their minds to misbehave.

Lasker Jury Chair Joseph Goldstein writes about the essence of creativity making parallels between art and science. He begins by quoting Oscar Wilde who has famously proclaimed that the most creative individuals are those who have taught their minds to misbehave.

Balzac’s Unknown Masterpiece: Spotting the next big thing in art and science

There is no shortage of advice on how to become a creative writer, a creative artist, or a creative scientist. Just in the last decade, hundreds of books and articles have been written on the subject, and in hundreds of TED lectures inspired thinkers have revealed their secrets for creative success. Despite this flood of contemporary advice, my favorite insight on creativity goes back over 100 years to the Irish playwright and wit Oscar Wilde. Wilde famously proclaimed that the most creative individuals are those who have taught their minds to misbehave.

One of the virtues of a misbehaving mind is that it endows one with the ability to spot the next big thing — whether it be in art or in science. A great example of a famous literary figure who passes the Oscar Wilde-‘misbehavior test’ with flying colors is the 19th century novelist Honoré de Balzac. In the 1830s, Balzac conceived the idea of writing a series of works that would describe the sweep and panorama of French society in all its splendor and squalor — from the highest aristocrats and politicians to the lowest swindlers and prostitutes. Over a 16-year period, he published a total of 91 novels and short stories, and shortly before his death in 1850, he organized his 91 works into a multivolume collection that he titled The Human Comedy. Balzac chose this title to contrast it with Dante’s The Divine Comedy, which portrayed the afterlife of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven and had nothing to say about the realism of the earthly life that Balzac presented. Balzac’s The Human Comedy contained many astute insights into human behavior. One of the most original and popular — and a prime example of his misbehavior — was his discussion about how certain people get ahead in life through advantageous marriages rather than hard work.

Balzac is responsible for a major literary innovation that has stood the test of time for nearly two centuries. He invented the device of serialization, in which the same characters appeared over and over again in his different books. Serialization has been adopted by hundreds of writers. Without serialization, J. K. Rowling would not be a billionaire with wealth exceeding that of Queen Elizabeth. Serialization accounts for the great popularity of contemporary television series, such as Downton Abbey and House of Cards.

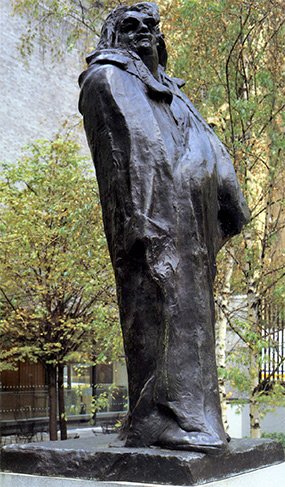

Figure 1. August Rodin. Monument to Balzac. 1897-1898. Bronze. Height, 9 feet 3 inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Rodin’s response to Balzac

Fifty years after Balzac’s death, the French government commissioned Auguste Rodin to create a sculpture in memory of the writer, whose work by that time had achieved international acclaim. To capture Balzac’s genius and the revolutionary nature of his work, Rodin decided to misbehave and create a revolutionary work of his own: rather than producing a realistic physical likeness of his subject, Rodin broke with the sculptural traditions of the past and created a semi-abstract figure in which only Balzac’s head remains visible, with the rest of his body wrapped in the dressing gown that he wore when writing (Fig. 1). Monument to Balzac, completed in 1898, is considered the first truly modern sculpture (1).

Like Balzac’s The Human Comedy, Rodin’s Balzac has stood the test of time. One of the best descriptions of Rodin’s sculpture is by the Belgian art critic André Fontainas: “Balzac stands with his huge head thrown back, alert like a wild animal, drinking in with eyes, nostrils, and lips and scenting the fever of the human comedy” (2). Bronze casts of Monument to Balzac are displayed at more than 50 different locations throughout the world, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum here in New York City, as well as in university art museums at Stanford and Oxford. It is one of the two or three most viewed sculptures in the world.

Balzac’s Unknown Masterpiece

One of Balzac’s most celebrated and intriguing stories, The Unknown Masterpiece (Le Chef-d’oeuvre inconnu), first published in 1831 and later integrated into The Human Comedy, deals with the subject of creativity at its most fundamental level; it tells the tale of an artist ahead of his time (3). The story is set in 17th century Paris in a studio located at 7 Rue des Grands-Augustins in the 6th arrondissement. The plot is simple. A famous aging artist, named Frenhover, is obsessed with finishing a painting that he has been secretly working on for 10 years and one that he claims will be his masterpiece — a painting that portrays a beautiful nude woman with such brilliance and artistic skill that she seems to be actually alive. When two younger painters who are great admirers of Frenhover’s work finally persuade Frenhover to let them see the secret canvas, they are appalled and shocked. All they see is an indecipherable jumble of strange lines and paint. As they stare in horror at the work, they mock the older artist and conclude that their celebrated hero has gone mad. Realizing his failure, Frenhover abruptly bids farewell to his two friends, burns his painting, and mysteriously dies during the night. The tragedy of Frenhover — and the brilliance of Balzac — is that the fictional artist had created the first abstract painting, inventing abstract expressionism 125 years before Jackson Pollock.

Picasso’s response to Balzac’s Unknown Masterpiece

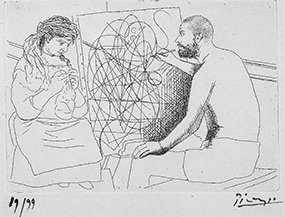

The artistic crisis that Frenhover faced in Balzac’s story exerted a profound effect on Cezanne, Matisse, and Picasso — all three of whom were artists of genius whose masterpiece paintings were so far ahead of their time that few of their contemporaries could recognize them as such. Picasso passionately identified with Frenhover’s failed quest for artistic perfection. In 1931, he produced 13 etchings that were included in the 100th anniversary reprint of Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece. These etchings deal with the theme of the artist working with his model.

Figure 2. Pablo Picasso. Painter with Model Knitting. 1927. One of 13 etchings from the special centenary edition of Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece. 19.5 x 21.8 cm. Exhibited at Juan March Foundation, Madrid, from October 2011 to February 2012.

Like Frenhover’s abstract painting, Picasso’s drawings were kept a closely guarded secret, and when they first appeared in the centenary book, some of them looked like a mass of lines and smudges of ink, such as the one shown in Fig. 2. The jumble of lines here was typical of Picasso misbehaving. Did the morass of lines represent the yarn of wool in the model’s hand, or was it meant to be Frenhover’s abstract painting? Today, Picasso’s 13 Balzac etchings are considered landmarks in the history of engraving. When a journalist asked Picasso what is the secret to his genius, he remarked: “When I was a child, I could draw like Raphael, but it took me a lifetime to draw like a child.”

Picasso was so haunted by the ghost of Balzac and by the tragedy of Frenhover that in 1936 he moved his studio to a townhouse located at 7 Rue des Grands-Augustins, the exact same building in which the setting for The Unknown Masterpiece took place 100 years earlier. It was at this same address that Picasso painted his greatest masterpiece, Guernica. Soon after Picasso moved into his new studio, German warplanes bombed the Spanish Basque city of Guernica, and Picasso immediately abandoned all projects and devoted full energy — night and day — to his one large canvas, which he completed within a record time of three months. At its unveiling in 1937 at the Paris Exhibition, Guernica — not surprisingly — perplexed the critics. But unlike the tragic Frenhover, the imperturbable Picasso was unfazed by the negative criticism, and he lived to see his work evolve from an unknown masterpiece to a highly celebrated one.

Richard Hamilton’s response to Balzac’s Unknown Masterpiece

In early 2010, the National Gallery of London invited the British painter and collage artist Richard Hamilton to stage an exhibit of his most recent work. At the time, Hamilton was 88 years of age and still exceptionally active and productive. The timing for an exhibit was remarkably propitious — Hamilton, like Picasso before him, had come under the spell of Balzac’s short story on the search for artistic perfection, and the National Gallery’s invitation would provide him a unique opportunity to express his ideas on The Unknown Masterpiece.

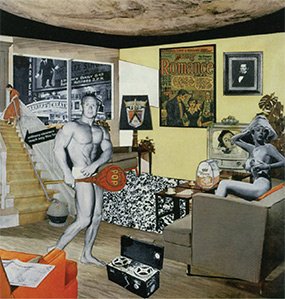

Figure 3. Richard Hamilton. 1956. Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? 26 x 24.8 cm. Collage. Exhibited at National Gallery, London, from February to May 2014.

A brief background on Richard Hamilton will help those not familiar with his career to appreciate how he responded to The Unknown Masterpiece. Hamilton is one of the most influential British artists of the 20th century. He is widely regarded as the founder of the Pop Art Movement in the 1950s, his work predating that of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein by several years. One of Hamilton’s early iconic works was a 1956 collage titled Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?, in which he used images cut from mass-circulation magazines (Fig. 3). The collage depicts a contemporary Adam and Eve — a muscleman holding a giant lollipop and a nude woman on a sofa with a lampshade on her head are enjoying their living room filled with all sorts of new consumables, including a tape recorder, a television, a vacuum cleaner, a canned ham on the coffee table, and a brand-new, comic-style painting on the wall.

According to the art critic John Russell, with this collage Hamilton “… single-handedly laid down the terms within which Pop Art was to operate” (4). In fact, the first time the word “Pop” ever appeared in a painting was when it was emblazoned on the lollipop at the center of Hamilton’s collage.

If anyone had a misbehaving mind in the Oscar Wilde sense, it was Richard Hamilton — the epitome of British pluck and profound originality. Over a 60-year career, he innovated, experimented, reinvented himself, and spotted the next big thing before any of his contemporaries. At age 80, Hamilton taught himself computer graphics. One of his most politically provocative computer-generated paintings, titled Shock and Awe, depicts a life-size Tony Blair dressed in a pistol-carrying cowboy costume, presiding over the invasion of Iraq. One shudders to think how Hamilton might have satirized George W.

Once Hamilton had mastered the intricacies of digital technology, he devoted his full energy, beginning in early 2010, to the National Gallery project: his homage to Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece. Using computer graphics, he composed a montage consisting of four known images that he assembled digitally and refined with the use of Photoshop’s Bezier’s curves; nothing was painted (5).

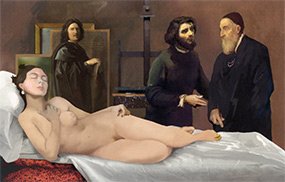

Richard Hamilton. Balzac (c). 2011 (printed 2012). 112 x 176 cm. Digital montage of known images. Epson inkjet on Hewlett-Packard RHesolution canvas. 112 x 176 cm. Exhibited at National Gallery, London, from October 2012 to January 2013.

The centerpiece of Hamilton’s digital montage is a reclining nude representing Frenhover’s muse (Fig. 4). Hamilton created this image from a digital scan of a photograph of a 19th-century nude whose pose harks back to Titian’s famous Venus of Urbino from 1583. The nude is surrounded by three famous artists (left to right) — Poussin, Courbet, and Titian. Titian represents Frenhover, and Poussin and Courbet represent Frenhover’s two younger artist-friends. The three artists were scanned digitally from reproductions of their well-known self-portraits. The three artists are all absorbed in deep thought, perplexed by the mysterious sensuality of the nude in front of them. A notable feature of the montage is the empty easel that is centrally placed between Poussin and Courbet. This H-shaped easel is identical to the one that Hamilton used in his studio and may be meant to represent the specter of Hamilton himself.

The reclining nude is perfectly shaped, but she appears unreal in her glossy skin — digitally exact, but artistically artificial. Within days after completing his digital montage, Hamilton died on the eve of his 90th birthday. His original intention was to use the digital montage as a guide for creating an authentic oil painting, which he believed would achieve Frenhover’s ideal of living purity that is missing in Hamilton’s pixilated version. As fate would have it, Hamilton’s “masterpiece,” like that of Frenhover, will remain forever an “unknown masterpiece” — a bittersweet irony if ever there were one. The empty H-shaped easel in the digital montage now takes on an eerie meaning that the misbehaving mind of Hamilton may or may not have intended. We will never know.

The misbehaving minds of Balzac, Rodin, Picasso, Hamilton, and Balzac’s Frenhover endowed each of them with the uncanny ability to spot the next big thing before anyone else. Spotting the next big thing is a distinguishing characteristic of scientists who win Lasker Awards and Nobel Prizes. As you will hear after lunch, this year’s Lasker winners were the first to spot the next big thing — how the endoplasmic reticulum senses harmful unfolded proteins and corrects them, how the tremors of advanced Parkinson’s disease can be alleviated by a surgical procedure, and how certain people with early-onset breast cancer owe their disease to an inherited gene, BRCA1.

References

Normand-Romain, A. L., Jurdin, C., and Pinét, H. 1898, le Balzac de Rodin. (Musée Rodin, Paris, 1998) pp. 1-463.

Musée d’Orsay. Works in Focus: Auguste Rodin Balzac. 2006.

de Balzac, H. The Unknown Masterpiece. Translated from the French by R. Howard and Introduction by A. C. Danto. (New York Review of Books, New York, 2001). pp. 1-135.

Russell, J. Introduction to Richard Hamilton. Exhibition Catalogue. (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1973). pp. 14-19.

Riopelle, C. and Bracewell, M. Richard Hamilton: The Late Works. Exhibition Catalogue. (National Gallery Co., London, 2012). pp. 1-64.