In 1963, Max Cooper decided to leave his job as a pediatrics instructor at Tulane University for a temporary research fellowship at the University of Minnesota Medical School. The move meant uprooting his wife and two young children, and on their first night in Minneapolis he woke "with a cold sweat in sheer terror." Cooper was worried that he had made a terrible mistake. "I knew I could be a good doctor," he says. "But starting again without any background in basic sciences I thought was pretty risky."

Max Cooper at the University of Minnesota in the mid-1960s

Courtesy of US National Library of Medicine

Still, Cooper was determined to learn how to perform lab research so that he could investigate the immune system and "produce something original on my own." Although he was initially allotted only three feet of space on the lab bench, he plunged into the work. "At one time I had 10 experiments going on," he recalls. One study, which involved probing chickens' immune capabilities, would prove to be a landmark, revealing two distinct armies of immune system cells, now known as B cells and T cells. The discovery not only uncovered a fundamental feature of the immune system but also explained the origin of some immunological diseases and led to improved treatments for certain cancers.

Cooper shared the 2019 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award with Jacques Miller of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Australia, who showed that the thymus—the organ in the neck where T cells develop—is crucial for immunity. "Miller has the distinction of being the only living scientist to have discovered the function of a human organ," a leading immunologist noted when the prize was announced. The two researchers are among more than a dozen scientists who have received a Lasker Award for delving into the immune system.

Spotlighting the Thymus

With careful experiments on mice, Jacques Miller showed that the thymus was not just a vestigial piece of tissue, as many researchers thought.

Courtesy of Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

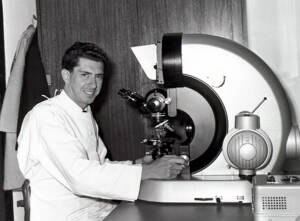

Miller started his research in the late 1950s as a PhD student at the Institute of Cancer Research in the UK. He was studying a type of mouse leukemia caused by a virus and that seemed to begin in the thymus. Miller could prevent mice from developing the cancer by surgically removing the thymus when the animals were newborns. But loss of the structure hobbled the rodents' immune system. When scientists transplant swatches of skin between strains of mice, the recipient's immune cells normally attack the foreign tissue. However, Miller discovered that mice missing a thymus didn't react to skin grafts from other mice or even from rats. The mice also often succumbed to infections. Implanting thymus tissue into the young mice restored their ability to fight off pathogens, he determined. Because older mice and adult humans survived just fine without a thymus, the consensus at the time was that the organ was useless. Miller challenged that view, concluding that it was prepping certain immune cells, known as lymphocytes, to defend the body. "The thymus at birth may be essential to life," he wrote.

Colored transmission electron micrograph of a section through the cortex of the thymus gland; thymocytes, which mature into T lymphocytes, are purple.

Courtesy of Jose Calvo / Science Source

His skin grafting experiments revealed another important function of the thymus. When he gave a mouse a skin graft and a thymus transplant from the same donor, the recipient's revived immune system did not attack the patch of skin. The rodent seemed to accept the foreign tissue. Miller showed that the thymus establishes self-tolerance, a key attribute of the immune system that prevents it from turning against the body's own tissues.

Dividing the Immune System

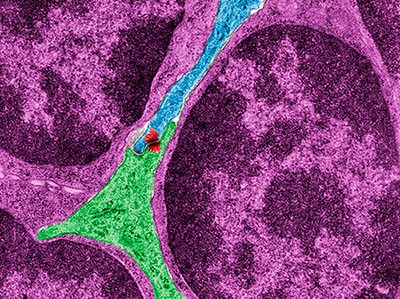

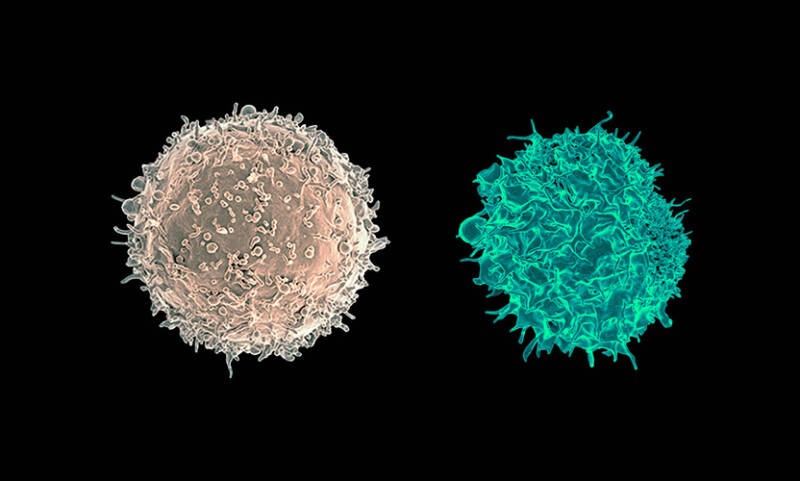

Cooper's work helped resolve a slew of contradictory and confusing evidence about lymphocytes. Scientists knew that some lymphocytes fought infections by releasing antibodies, but where those cells came from was unclear. Cooper found a key clue in a journal that most immunologists never read: Poultry Science. A report suggested that, at least in chickens, a mysterious organ called the bursa of Fabricius that branched off the hindgut was essential for producing antibodies. To test that possibility, Cooper dosed newly hatched chicks with radiation to kill off any lymphocytes in their bodies. He then surgically removed the thymus, the bursa of Fabricius, or both structures. The birds lacking a bursa couldn't make antibodies but still had plenty of lymphocytes. By contrast, chickens without a thymus could still fashion antibodies but were low on lymphocytes.

The findings, which Cooper and colleagues published in 1965 and 1966, "split the immune system in a striking way," he says. The birds boasted two immune branches. One branch, which scientists now know consists of B cells, stemmed from the bursa; the second branch, now referred to as T cells, depended on the thymus. That conclusion clashed with the prevailing view that all lymphocytes belonged to the same lineage and derived from the thymus, Cooper says. "You could see how [the results] would change everything. It was exciting." During the week after he made the discovery, "I had less sleep than I had ever before in my life," he says.

Transmission electron micrograph of a B cell (left) and a T cell (right) from a human donor

Courtesy of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health

The human immune system shows the same division. People don't have a bursa of Fabricius—our B cells are born in the bone marrow. The precursors of our T cells also originate there and then travel to the thymus, where they mature. Miller and Cooper worked independently, but their research meshed and led to a new understanding of how the immune system is organized and functions. As one immunologist wrote, "the legacy of Cooper and Miller's discoveries have reverberated through both basic and translational immunology for over 50 years."

When T Cells Attack

Cell surface molecules known as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins are crucial for our immune defenses. They help mobilize lymphocytes to battle invading pathogens and allow immune cells to discriminate healthy cells from cancerous or infected cells. Five scientists shared the 1995 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award for elucidating the functions and structures of those vital proteins. Two of the researchers, Peter Doherty and Rolf Zinkernagel, who were at the John Curtin School of Medical Research in Canberra, Australia, when they performed the work, also received the 1996 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

Doherty says that he and Zinkernagel didn't expect to make an immunological breakthrough. A veterinary pathologist, Doherty was "going on to a career in the food-producing industry," he says. He was at the institute to learn basic immunology techniques that he could apply when he returned to his veterinary work. Zinkernagel, who had just arrived from the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, also was in Canberra to brush up on his immunological knowledge. When they began to collaborate in 1973, "we were two naive young guys," Doherty recalls.

The pair wanted to better understand how viruses cause brain inflammation and experimented with a mouse virus called LCMV. The scientists were following up on the hypothesis that an invasion of inflammation-producing cytotoxic T cells triggered neurological disease in the animals. Sure enough, when isolating the inflammation-inducing cells from the brains of infected mice, the researchers found plenty of potent cytotoxic T cells. The duo also determined that those cells killed lab-grown mouse cells harboring the virus.

Left to right: Don Graig Wiley, Rolf Martin Zinkernagel, Peter Charles Doherty, Jack L. Strominger, Emil R. Unanue, and Barry J. Marshall at the 1995 Lasker Awards Ceremony

Had the researchers stopped there, Doherty wouldn't be, as he puts it, "the only vet to win a Nobel Prize." However, Zinkernagel and Doherty also asked whether the cytotoxic T cells attacked virus-carrying cells from other mouse strains. They didn't. "A lightbulb went on," Doherty says. "We said, 'we'd better follow this up.'" The researchers' later work suggested that cytotoxic T cells scanning for infected cells don't just check for viral molecules. The molecules also have to be attached to MHC proteins on a cell's surface. That requirement explained why T cells from one mouse strain did not react to virally infected cells from other strains. The strains sported different versions of MHC.

The duo's discovery, which they initially described in Nature in 1974, transformed researchers' understanding of how the immune system discerns friend from foe. Scientists had thought that T cells detect invaders by attaching to foreign molecules, Doherty says. Instead, the results suggested that the immune cells search for "altered self," an MHC protein modified by viral infection.

The type of MHC molecule that Doherty and Zinkernagel studied is known as MHC I. Two other Lasker winners from 1995, Jack Strominger and Don Wiley of Harvard, teamed up to decipher the protein's molecular structure. Strominger "drove an enormous effort to grow buckets of human cells" so that he could isolate enough of the rare molecule to analyze, Doherty says. In 1987, Strominger and Wiley revealed that the surface of MHC I features a slot where pieces of pathogen molecules can fit to form the altered self that Doherty and Zinkernagel postulated.

MHC I occurs on almost all cells in the body and allows the immune system to identify and cull virally infected cells. The fifth winner of the 1995 Lasker award, Emil Unanue of Harvard Medical School, studied its molecular cousin MHC II, which is limited to a few types of cells, mainly immune cells. During an infection, those cells affix fragments of pathogen molecules to MHC II and show the combination to T cells, which then stimulate other lymphocytes to counterattack. In studies starting in the 1960s, Unanue dissected the process in the immune cells known as macrophages. After a macrophage consumes a pathogen, he found, the cell only partially digests the victim's proteins and transfers the remnants to the MHC II molecules for display on the membrane.

Immune Cells Branch Out

Intrigued by unusual cells he saw under the microscope, Ralph Steinman, here working in his lab at Rockefeller University in 1992, showed that dendritic cells had a key role in immune defense.

Courtesy of Rockefeller University

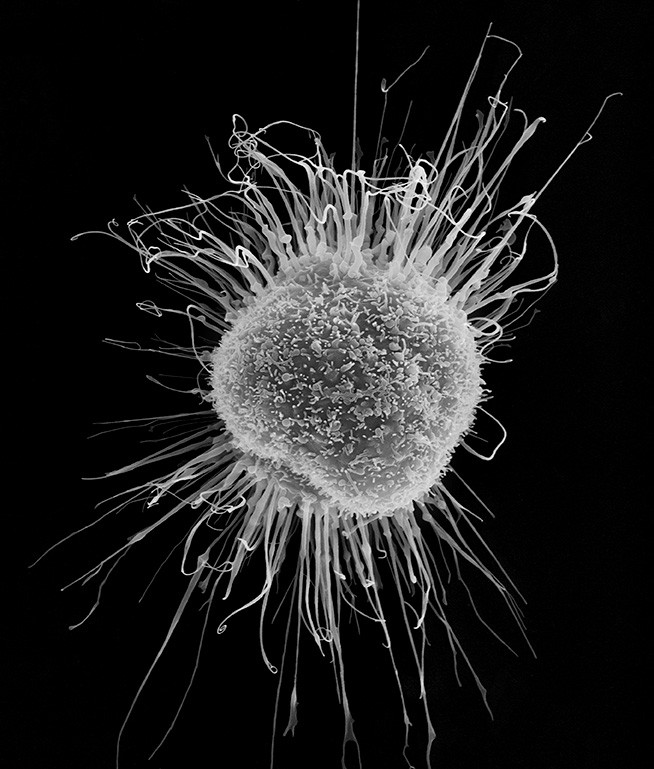

In 1973, immunologist Ralph Steinman of Rockefeller University was peering through a microscope at a sample from a mouse's spleen when he noticed some strange-looking cells whose many branches reminded him of trees. Steinman had discovered dendritic cells, which are among the most powerful immune cells. "They are sentinel cells that sit in our tissues," especially in parts of the body that contact the environment, such as the skin and lungs, says immunologist Jatin Vyas of Columbia University, who wasn't connected to Steinman's work. Dendritic cells lie in wait for pathogens trying to infiltrate the body. If a pathogen is detected, the cells show off portions of molecules from the interloper and help mobilize T and B cells to take it on. For identifying dendritic cells and teasing out their functions, Steinman won the 2007 Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research and shared the 2011 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. "For fundamental immunology, his impact is huge," says Gwendalyn Randolph, an immunologist at Washington University.

At first, however, many immunologists dismissed dendritic cells, thinking that the rare cells couldn't take on such an important task. Thanks to Unanue's research, researchers believed that the much more abundant macrophages did the job. "Emil and Ralph were archrivals," Randolph says. The two scientists disputed the contributions of dendritic cells versus macrophages. But Steinman and colleagues methodically built a case for dendritic cells, proving that they were distinctive, that they stimulated T cells in the culture dish, and that they were active in the body. Steinman's research "was always step by step and not splashy," Randolph says.

Human dendritic cell, scanning electron micrograph

Courtesy of Dennis Kunkel Microscopy / Science Source

Steinman's holistic approach powerfully influenced immunologists' thinking, Vyas says. The immune system features what scientists term an adaptive arm, the B and T cells that target specific pathogens but are slow to get rolling when an infection begins. By contrast, the innate arm consists of first responders always ready to rumble if a threat appears. When Steinman started his work, Vyas says, researchers who studied the adaptive immune system usually ignored the innate immune system and vice versa. "There were two camps, almost like sects in a religion," he says. "Along comes Ralph, and he asked how they connect." He wasn't the first scientist to pose the question, Vyas says, but he answered it. Dendritic cells turned out to be the missing link between the two immune arms. They are innate cells, but they reach out to adaptive cells to trigger immune responses to pathogens.

DIY Antibodies

More than 200 drugs around the world are monoclonal antibodies, lab-made versions of the defensive proteins that B cells produce in our bodies. The category includes five of the top-selling medications, among them the cancer treatment pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and the rheumatoid arthritis therapy adalimumab (Humira). Marc Feldmann and Ravinder Maini of Imperial College London shared the 2003 Albert Lasker Clinical Research Award for showing that the monoclonal antibody infliximab (Remicade) reduces the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. James Allison of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center earned the 2015 Lasker~DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award for harnessing monoclonal antibodies to unleash immune cell attacks on tumors. Many medical tests, including those for COVID-19 infection and pregnancy, rely on monoclonal antibodies. The proteins also are powerful research tools, allowing scientists to track proteins and identify cell types, among other tasks.

Michael Potter examines tissue from a mouse tumor under the microscope in 1984.

Courtesy of office of NIH History and Stetten Museum

That chemical cornucopia stems largely from the work of César Milstein, an immunologist at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in the UK, and his postdoc Georges Köhler. In 1975 the duo devised the first technique for making monoclonal antibodies. Nine years later, the pair, along with Michael Potter of the National Cancer Institute, received the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award. That was a banner year for Milstein and Köhler, who also shared the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine with a third researcher. The clinical impact of Milstein and Köhler's work "is colossal," says Terence Rabbitts, a molecular immunologist now at the Institute of Cancer Research and Milstein's former postdoc.

Cesar Milstein and Georges Köhler, here in 1982, wanted a better way to make antibodies for research. Their technique led to an explosion of new drugs and scientific tools.

Courtesy of Celia Milstein/MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

Potent drugs and research tools are made by antibodies because they are specific. Each one latches onto a particular portion of a molecule, say, on the surface of a virus or protruding from a cancer cell. Potter's research brought a better way to produce antibodies. In the 1950s, he began triggering tumors in mice by exposing the animals to various chemicals. However, he struggled to produce one type of tumor derived from abnormal plasma cells, the antibody-producing versions of B cells. Those growths could be medically informative because in patients with multiple myeloma, tumors composed of plasma cells sprout in the bones or elsewhere in the body. Potter could induce plasma cell tumors by injecting mice with mineral oil or other substances, as he and a colleague revealed in Nature in 1962.

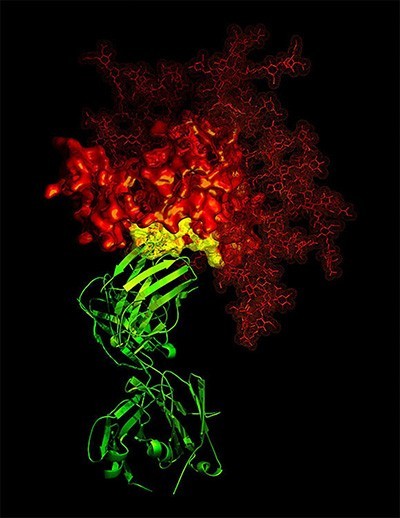

3-D X-ray crystallographic image showing the broadly neutralizing antibody B12 (green ribbon) in contact with a critical target (yellow) for vaccine developers on HIV-1 gp120 (red)

Courtesy of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health

More than a decade later, Milstein's lab was using mouse myeloma tumors similar to those Potter had generated to probe how B cells make antibodies. In those days, "if you wanted an antibody, you got a sheep," Rabbitts says. Researchers would inject a substance into the animal and then filter the resulting antibodies from its blood. A far superior approach emerged from what Milstein called a "little experiment being done in the background." One of his students had found that a particular virus could spur two myeloma cells to merge. The resulting hybrid cell churned out the antibodies from both of its parents.

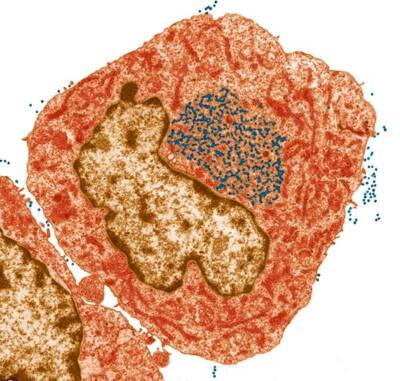

Colored transmission electron micrograph of mouse leukaemia virus particles (blue dots) inside and outside a hybridoma cell which is used in the production of monoclonal antibodies

Courtesy of Steve Gschmeissner / Science Source

When Köhler joined the lab as a postdoc, he and Milstein decided to adapt the approach to make a hybrid cell that yielded only one type of antibody. They coaxed myeloma cells to combine with mouse spleen cells that fashioned antibodies against sheep blood. The "offspring" of that union, which they described in a 1975 report in Nature, produced a specific antibody against sheep cells. Because the hybrid cells continue to divide in culture, the researchers could make large amounts of that antibody or any other one they wanted. Milstein and Köhler's breakthrough led to mass production of monoclonal antibodies for medicine and research. That wasn't their intention, Rabbitts says. But once they developed the technique, "they said, 'oh, this is useful for something else.'"

Mix and Match DNA

The human immune system has its work cut out. Almost 300 kinds of viruses can make us sick, along with swarms of bacteria, fungi, and parasites. The immune system can fend off a wide range of potential invaders because it deploys a huge diversity of defenses. A person can make about 10 billion types of antibodies, each of which homes in on a different molecular target. Leroy Hood of the California Institute of Technology, Philip Leder of Harvard Medical School, and Susumu Tonegawa of MIT shared the 1987 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award for piecing together how immune cells create that enormous variety. Tonegawa also won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine the same year. The trio enlisted new molecular biology techniques, and together their work helped reveal that immune cells make antibodies by reshuffling parts of their DNA, jettisoning some segments and then stitching the remaining portions together to form functional genes.

Illustration of a human immunoglobulin G1 antibody, two light chains (red and purple) and two heavy chains (cyan and green)

Courtesy of Thom Leach / Science Source

When the three scientists started investigating antibody diversity in the 1970s, that mechanism wasn't the only possible explanation. Some researchers argued that cells could make so many types of antibodies because they harbored many antibody genes. Scientists hadn't yet sequenced the human genome, so the hypothesis was plausible. Leder's research helped knock down the idea. Researchers had determined that antibodies consist of two light chains of amino acids and two heavy chains. In turn, the light chains contained a constant region that remained the same from antibody to antibody and a variable region that differed. In 1974, Leder and colleagues searched the mouse genome for all the DNA segments coding for the constant region. If DNA included many antibody genes, many duplicates of the constant region should exist. However, the researchers found that mice carried only two or three copies. In 1978, Leder and his team analyzed the DNA for the light chain and confirmed that cells were rearranging the variable and constant regions.

Left to right: Philip Leder, Susumu Tonegawa, Michael DeBakey, Mary Lasker, James Fordyce, Mogens Schou, Leroy Hood at the 1987 Lasker Awards Ceremony

Hood says he began investigating antibodies because human complexity intrigued him. "I thought it would be cool to study immunity," he says, where that complexity was extreme. Research from his lab revealed new mechanisms that increase diversity by allowing B cells to diversify their antibodies. In 1974, for instance, his group discovered that at least eight segments can code for the heavy chain variable region in mice. In 1980, Hood and colleagues found that the DNA that encodes the heavy chain contains an unexpected segment, which they dubbed D for "diversity," adding to the possible number of combinations that the cells can create.

Tonegawa's work stands out, Rabbitts says, because it was comprehensive. Other scientists considered different aspects of the DNA rearrangement mechanism, but "he did everything." For instance, he and his colleagues showed that cells were paring and rearranging the DNA that coded for antibodies. The researchers compared DNA from embryos to that of myeloma cells churning out antibodies. The DNA didn't match. For instance, the DNA from the myeloma cells was missing a section between the variable and constant regions. Moreover, the scientists pinpointed a portion of another DNA segment, the J (joining) region, that had jumped to the end of the variable region, another mechanism to increase diversity.

Researchers now know that in humans, the DNA for the heavy chain starts out with two constant regions, 45 variable regions, 27 D regions, and six J regions. Like a diner ordering from an à la carte menu, a maturing B cell selects one region from each category and then links them to form a heavy chain gene. The cell scraps the other segments. Although Leder, Hood, and Tonegawa did not train as immunologists, their results revolutionized immunology. "It's amazing to think that this system evolved to produce antibody diversity," Rabbitts says. Their work also overturned the long-standing dogma that the DNA in our cells never changes.

Together, these Lasker winners helped uncover the immune mechanisms that protect us from microbes, cancer, and other dangers, and their insights formed the basis for groundbreaking research tools, diagnostics, and medications.

By Mitchell Leslie