By Joseph L. Goldstein

Truly creative works of science and art produce unexpected and surprising results–just like the punch line of a good joke that generates an unfamiliar twist on a familiar idea. Surprise stimulates curiosity, which triggers a search to reveal the mystery of things unknown.

Introduction

Nothing is more thrilling to a scientist than to obtain an unexpected and surprising result—a result that makes us think in ways we have never thought before. Over the last 75 years, Lasker Awards have been given for many basic discoveries and clinical advances that came as total surprises. To name a few of these surprises—there's the double helix, cyclic AMP, recombinant DNA, gene splicing, monoclonal antibodies, Helicobacter causing ulcers, prions, in vitro fertilization and drugs that cure hepatitis C.

Surprise is closely related to creativity, and creativity is closely related to surprise (Koestler, 1964; Boden, 2010; Luna and Renninger, 2015). Anything that is truly creative produces surprise, and surprise produces creativity by stimulating curiosity, which triggers a search to reveal the mystery of things unknown. Many such mysteries are solved when the scientist or the artist—like the comedian—generates unfamiliar combinations of familiar ideas (Asimov, 2014). Successful standup comedians are endowed with a creative knack for thinking outside the box. They can put two and two together to make five—the punch line of their joke, which occurs suddenly when the comedian abruptly changes course, steering the audience to a totally different context (Koestler, 1964; Rosenfield, 2017).

The theory that the structure of a good joke depends on creativity and surprise was advanced in a 1964 book The Art of Creation by Arthur Koestler (1964), one of the most influential intellectuals and authors of the 20th century. Koestler analyzed a joke that Sigmund Freud liked to tell about a Marquis in the court of Louis XV who enters his bedroom to find a bishop making love to his wife. After observing them in flagrante, the Marquis calmly steps to the window, opens it, and extends his arms, blessing the people on the street below.

"What are you doing?" screamed his anguished wife.

"The bishop is performing my functions," replied the Marquis, "so I am performing his."

The joke works, explains Koestler, because the Marquis' behavior is a total surprise, "both unexpected and perfectly logical—but of a logic not usually applied to this type of situation." The listener expects the Marquis to respond with outrage, but instead he acts according to his day-to-day job description. "It is the sudden clash between these two mutually exclusive codes of rules that produces the comic effect." (Koestler, 1964).

Magritte: Master of the Visual Punch Line

The juxtaposition of the familiar with the unfamiliar is the essence of the punch line that creates the surprise element of a good joke. In the world of art, the master of the visual punch line is the surrealist painter René Magritte (Sylvester, 1992; Hughes, 2002). During his 45-year career in the first half of the 20th century, Magritte produced more than 1500 paintings that evoke unexpected surprises by juxtaposing familiar objects in unfamiliar settings. His surprising juxtapositions challenge us to think in different ways.

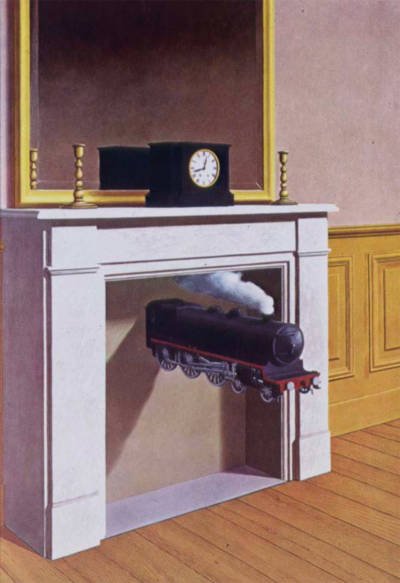

Figure 1. Time Transfixed

René Magritte (1938). Oil on canvas. 30 x 26 in. Art Institute of Chicago. ©2021 C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

One of Magritte's most widely viewed and critically discussed works is a painting entitled Time Transfixed (Figure 1), which has been in the permanent collection of the Art Institute of Chicago for the last 50 years (Sharp, et al. 2009). Here, Magritte juxtaposes two objects—a fireplace and a train—that do not normally belong together. The only thing they have in common is that both burn fuel. The train is situated in the fireplace so that it appears to be emerging from the mouth of a railway tunnel. Above the fireplace is a tall mirror onto which only a clock and a candlestick on the mantel are reflected. The blankness of the mirror suggests an empty bleak room, which suddenly becomes disrupted by a noisy intruder from the outside world—the train racing full steam through the fireplace.

How did Magritte come up with such a mysterious title like Time Transfixed? Time Transfixed is the English translation of the original French title La Durée poignardée, which literally translates as "Ongoing Time Stabbed by a Dagger." Magritte much preferred this French title, which evokes the absurdity of a quiet, still room suddenly being stabbed by a train jutting through the fireplace. Magritte produced Time Transfixed in 1938 for one of his patrons and he urged it to be hung at the bottom of his staircase so that the train would "stab" into the subconscious of his guests as they made their way up to the ballroom. Ironically, the patron hung the painting over his fireplace! (Sharp, et al. 2009).

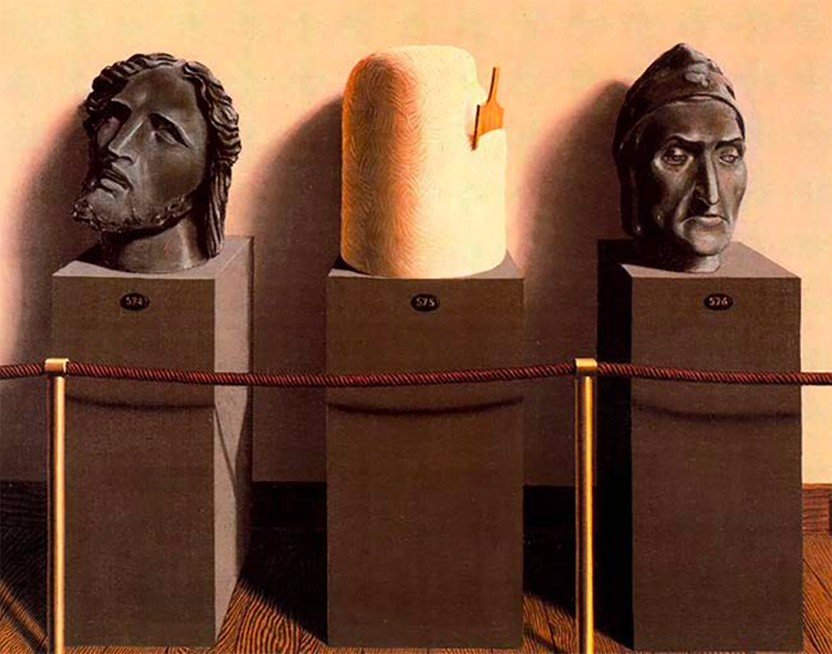

One of my favorite works by Magritte, entitled Eternity, does not involve smoke and mirrors like Time Transfixed, but it epitomizes Magritte's surreal "smoke and mirrors" style and illustrates how he uses the element of surprise to shake us out of the habit of conventional thinking (Figure 2). Here, Magritte paints a scene from a museum. Behind the velvet rope stand three sculptures: the head of Jesus on the left, the head of Dante on the right, and in the middle is a block of butter. The conventional interpretation of this unusual painting is that the eternal truths of religion and poetry will remain forever and never melt away. The more maverick interpretation is that religion and poetry are not eternal and will melt away with the passage of time just like the block of butter.

Figure 2. Eternity

René Magritte (1935). Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art, New York. ©2021 C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

A major challenge for committees that select science prizes, like the Lasker Jury and the Nobel Committee, is to choose winners whose work passes the "Magritte Eternity Test", i.e., work that will stand the test of time and never melt away like butter.

During his 45-year career, Magritte produced more than 1500 paintings, but less than a dozen sculptures. I think it's harder to be original in sculpture than in painting, especially if you want to create provocative sculptures that produce surprise and question traditional thinking and perception.

The Magritte of Sculpture: The Duo Team of Elmgreen and Dragset

Twenty-six years ago, two Scandinavian artists, Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, began working together, and they have now created over 100 large public sculptures that juxtapose familiar objects in unfamiliar settings much the way Magritte did in painting. Their work is compelling, provocative, beguiling, and full of wit and surprises, which stimulates us to think creatively (Smith and Rashid, 2018; Arnold and Iannacchione, 2019).

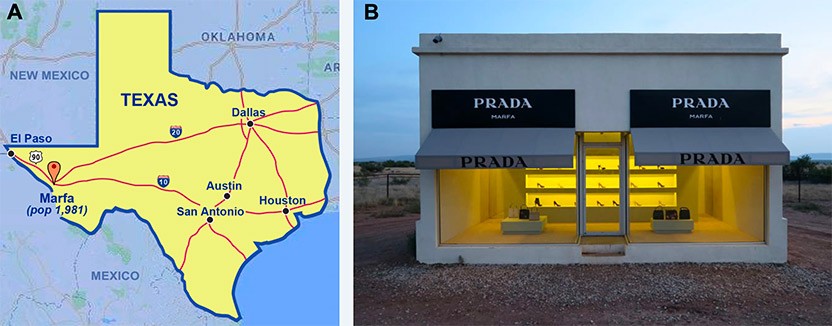

In 2005, Elmgreen and Dragset made a cross-country tour of the U.S. and were especially intrigued with a country road in the West Texas desert leading from El Paso to the small town of Marfa (Figure 3A). In a desolate setting devoid of any urban context, they erected a sculpture, entitled Prada Marfa, that emulates the style and displays of Prada's signature luxury boutiques (Figure 3B). But the one difference between Prada Marfa and Prada shops in large cities around the world is that Prada Marfa is not open for business. For the last 16 years, Prada Marfa has become a pilgrimage site that attracts thousands of fashion fans, most of whom remain totally oblivious to the absurdity of branding and consumerist culture.

Figure 3. A Prada Boutique in the Middle of the West Texas Desert

(A) Map of Texas showing location of town of Marfa near El Paso.

(B) Prada Marfa. Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset (2005). Permanent installation located 26 miles northwest of Marfa, TX (population 1981). Adobe bricks, plaster, aluminum frames, glass panes, carpet, canvas, Prada shoes and bags. 16 x 25 x 15 ft. ©2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISDA.

Trafalgar Square in London is one of the great tourist spots in the world and is surrounded by four large pedestals, called the Four Plinths. One of the four plinths carries a sculpture of King George IV on horseback, and the second and third plinths are occupied by sculptures of famous military men. The Fourth Plinth, an imposing slab of marble erected in 1841, remained bare until 1999 when the City of London decided to showcase large contemporary sculptures on top of the empty pedestal (Perry and Vasconcellos, 2016). Each selected sculpture adorns the base slab for a period of 1.5 to 2 years. In 2012, Elmgreen and Dragset won the competition for a spot on the Fourth Plinth.

Figure 4. Boy with No Power Amidst Powerful Historical Heroes in London's Trafalgar Square

Powerless Structures, Fig. 101. Elmgreen and Dragset (2012). Bronze. Exhibited on the Fourth Plinth at Trafalgar Square, 2012-2014. 14 x 6 x 15 ft. ©2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISDA.

They displayed a sculpture of a playful young boy on a rocking horse, elevating the child to the status of a historical hero, although there was no history to commemorate (Figure 4). Instead of praising the past heroism of the powerful, the work celebrates the potential heroism of growing up and questions the English tradition of building monuments predicated on military victory or defeat.

A Modern Rendition of Van Gogh's Ear and the Biblical Moses

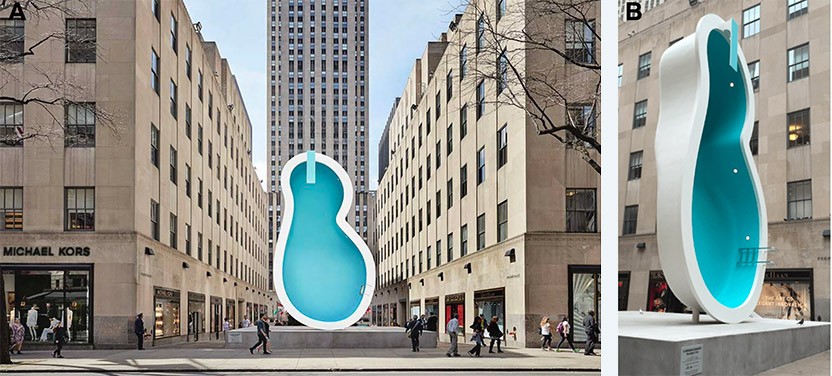

Elmgreen and Dragset's most recent large public sculpture was installed in 2016 at Rockefeller Center on Fifth Avenue. Since it's hard to surprise the sophisticated New Yorker who knows it all and has seen it all, the artists had to come up with something really cagy and intimidating. They installed an upright, 66-foot tall sculpture shaped like an empty swimming pool and turned the pool on its side. They titled it Van Gogh's Ear (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Van Gogh's Ear

Elmgreen and Dragset (2016). Fiberglass, stainless steel, lacquer, lights. Exhibited at Rockefeller Center, New York, NY, 2016. 30 x 16 x 8 ft. ©2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISDA.

At one level, the sculpture was designed as a comical homage to Van Gogh's infamously separated body part. Van Gogh's Ear was also meant to poke fun at the frenetic behavior of New Yorkers and visiting tourists who rush down Fifth Avenue, but who would be much better off relaxing by the pool.

Figure 6. Modern Moses

Elmgreen and Dragset (2006). Baby carrycot, wax figure, baby clothes, stainless steel cash machine. Baby Carrycot, 6 x 28 x 15 in. Cash machine, 38 x 25 in. ©2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISDA.

Although virtually all of the Elmgreen-Dragset work provokes and teases the viewer's mind, none has evoked more surprise and shock than the sculpture entitled Modern Moses (Figure 6). This artwork features a wax baby in a cot abandoned at a non-functioning ATM machine (Arnold and Iannacchione, 2019). As we were taught in Sunday school, the biblical story of Moses took place 3000 years ago when Moses' mother hid him in a basket next to a river so he would not be harmed. When Modern Moses was first exhibited in London in 2006, it was interpreted as a critique of the British government's failure to fund social programs to help needy children. When shown in the U.S. several years later, the artwork took on a more poignant and direct meaning, referring to the "Baby Moses Safe Haven" laws in most states, which allow parents to leave infants at any hospital or fire station with "no questions asked." Then, in 2016 when Modern Moses was shown in Beijing, its meaning shifted in a different direction, namely to the concern among the Chinese that a professional career is considered more important than having children. It will be fascinating to learn how Modern Moses is perceived when it is exhibited in the Holy Land of the real Moses.

The Elmgreen-Dragset Rules for Judging Lasker Nominations

One of Elmgreen and Dragset's sculptures is relevant to the way the Lasker Jury deliberates in choosing its awardees (Figure 7). The artists created a real judicial wig out of horsehair and hung it on a steel hanger with the outline of the judge's head and face taking shape in the void (Smith and Rashid, 2018). Elmgreen and Dragset are reminding us that the headless wig offers a way for depersonalizing the wearer who writes the rules by which we all must abide.

So when our Lasker Jury convenes to evaluate nominations, the members of the committee are instructed to follow the rules implied in the sculptures of Elmgreen and Dragset—namely, 1) discard your biases; 2) focus on originality, boldness and impact; and 3) pay special attention to the element of surprise.

Figure 7. Heritage

Elmgreen and Dragset (2014). Original judge's wig on a steel hanger. 48 x 14 x 14 in. ©2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VISDA.

2021 Lasker Awards: Unexpected Surprises Spur Scientists to New Heights of Discovery

Like the art of Magritte and Elmgreen & Dragset, the accomplishments of this year's Lasker Awardees illustrate how surprising and unpredictable findings stimulate new insights and ideas. In an interview several months before his death in 2020 at age 96, the legendary physicist/mathematician and immensely creative thinker Freeman Dyson expressed his views on the origin of scientific discovery: "The beauty of science is that all important things are unpredictable. The optimistic view in me is that nature is designed to make the universe as interesting as possible" (Mack, 2020). In keeping with Dyson's views on unpredictability, the discoveries of this year's Lasker winners began as surprise findings that no one could have imagined would turn out to be important. Moreover, not to disappoint Dyson, the discoveries have also made the world a more beautiful and interesting place.

Basic Award

The 2021 Lasker Basic Medical Research Award honors three scientists, Dieter Oesterhelt (Max-Planck-Institut für Biochemie, Martinsried), Peter Hegemann (Humboldt University Institute of Biology, Berlin) and Karl Deisseroth (Stanford University), for the discovery of light-sensitive microbial proteins that can activate or silence individual brain cells and for their use in developing optogenetics—a revolutionary technique for neuroscience.

Who would have imagined that a light-sensitive, rhodopsin-like protein—containing the vitamin A-related retinal cofactor and isolated from purple membranes of a salt-loving archaea—would be the key to developing a powerful technique for probing the function of individual neurons and their circuitry?

Clinical Award

The 2021 Lasker~DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award honors two scientists, Katalin Karikó (BioNTech RNA Pharmaceuticals, Mainz, Germany) and Drew Weissman (University of Pennsylvania) for the elucidation of a new therapeutic technology based on nucleoside modification of messenger RNA—enabling rapid development of the highly effective Covid-19 vaccines.

Who would have imagined that a simple and subtle chemical modification in a synthetic messenger RNA molecule would make it possible for two biopharmaceutical companies to develop and distribute–within one year—a safe and potent vaccine against the deadly SARS-CoV-2 virus?

Special Achievement Award

The 2021 Lasker~Koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science honors only one scientist—but one who is arguably the premier biomedical scientist of the last five decades. David Baltimore (California Institute of Technology) is renowned for the breadth, depth, and beauty of his discoveries in virology, immunology, and cancer; for his academic leadership; for his mentorship of hundreds of scientists, many of whom occupy prominent positions throughout the world; and for his influence as a public advocate of science.

Who would have imagined that a scientist with a winning streak of brilliant bench discoveries (reverse transcriptase, RAG recombinase genes, NF-kB, and Abelson virus tyrosine kinase) would be the same person who took on multiple leadership responsibilities (founder of Whitehead Institute, President of Rockefeller University, President of California Institute of Technology, President of AAAS) and become a spokesperson for science on many national policy issues including recombinant DNA, the AIDS epidemic, and human gene editing?

References

Arnold, L. and Iannacchione, A. (2019). Elmgreen & Dragset: Sculptures. (Hatje Cantz, Berlin).

Asimov, I. (2014). On creativity: how do people get new ideas? MIT Technology Review: 118: 12-13.

Boden, M.A. (2010). Creativity and Art: Three Roads to Surprise. (Oxford University Press).

Hughes, R. (2002). The Portable Magritte. (Universe Publishing, New York).

Koestler, A (1964). The Art of Creation. (Penguin Group, London). pp.33-35; 87-97.

Luna, T. and Renninger, L. (2015) Surprise. (Tarcher Parigee, New York).

Mack, K. (2020). Freeman Dyson's quest for eternal life.

Perry, G. and Vasconcellos, I. (2016) Fourth Plinth: How London Created the Smallest Sculpture Park in the World. (Art / Books, London).

Rosenfield, S. (2017). Mastering Stand-Up: The Complete Guide to Becoming a Successful Comedian. (Chicago Review Press).

Sharp, R., Stepina, E., and Weichemeyer, S., eds. (2009). The Essential Guide: Art Institute Chicago. 3rd ed., The Art Institute of Chicago. p. 264.

Smith, L., and Rashid, H. (2018). Elmgreen & Dragset: This Is How We Bite Our Tongue. (Whitechapel Gallery, London).

Sylvester, D. (1992). Magritte: The Silence of the World. (Henry N. Abrams, Inc., New York).