Opening remarks from the 2017 Lasker Awards ceremony

Opening remarks from the 2017 Lasker Awards ceremony

Lasker Jury Chair Joseph Goldstein considers how great artists, like great scientists, create puzzles that invite reinterpretation and reevaluation over generations and across centuries.

The Spanish artist Diego Velázquez created a puzzle-painting 360 years ago that to this day remains unsolved, but still mystifies and intrigues. Unlike artists who get their thrills by creating puzzles that stimulate the imagination, scientists get their kicks by solving puzzles that advance biomedical research.

Kicks and Thrills

According to the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, the successful scientist is a passionate puzzle-solver who relishes the challenge to solve problems in which “the outcome remains very much in doubt.” The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman expressed a similar view when he proclaimed that puzzle-solving is the primary motivation for becoming a scientist. To quote Feynman, “The prize is the pleasure of finding the thing out, the kick in the discovery.” Feynman’s “kick in the discovery” is like the thrill of having a eureka moment.

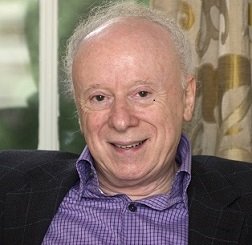

One difference between scientists and artists is that scientists like to solve puzzles by putting the pieces together, while artists get their kicks by creating the pieces. Among artists, the Belgian surrealist René Magritte (1898-1967) is the consummate creator of puzzle-paintings. During his 40-year career, Magritte painted more than 1600 visual puzzles that juxtaposed two or more ordinary objects in an unusual context that gave new meaning to familiar things. One of Magritte’s puzzle-paintings, Les Idées Claires (Clear Ideas), is relevant to scientific discovery (Figure 1). Here, you see a rock over the ocean and underneath a cloud. The cloud represents our murky ideas. When these murky ideas crystallize and solidify, our whole being, like the rock, is uplifted into the sky, producing the kick and thrill of discovery.

Figure 1. Les Idées Claires (Clear Ideas)

René Magritte (1958). Oil on canvas. 20 x 24 in. Private Collection © 2017 C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Velázquez’s Las Meninas: The Ultimate Puzzle-painting

Magritte may hold the record for the largest number of puzzle-paintings, but it is the 17th century Spanish artist Diego Velázquez who created the ultimate puzzle-painting — the famous Las Meninas (Portuguese for The Maids of Honor), completed in 1656 (Figure 2). Few paintings in the history of art have generated so much critical analysis with so many different interpretations. The fascination with Las Meninas derives from its large canvas (10.5 by 9 feet) with life-sized figures, the complex composition of its cast of characters, the seductive nature of its riddles and puzzles, and the artist’s ability to create a visual world that seems palpable to the viewer (Carminati, 2012).

Figure 2. Las Meninas (Maids of Honor)

Diego Velázquez (1656). Oil on canvas. 10.5 x 9 ft. Prado Museum, Madrid.

At first glance, the subject of Las Meninas seems straightforward. The setting takes place in Velázquez’s studio in the royal palace in Madrid. At the center of the painting stands the young princess, the 5-year-old Infanta Margarita, surrounded by her entourage consisting of two maids of honor, two dwarfs, and a dog (Figure 2). Just behind the maid at the right is a lady-in-waiting chatting with a bodyguard. At the left, Velázquez portrays himself in front of an enormous canvas, glancing out beyond the pictorial space. On the center back wall, the Queen’s chamberlain stands in a lighted doorway. To the left of the doorway is a mirror that reflects the blurred faces of the King and Queen of Spain, who are apparently standing just outside the pictorial space in the same place where museum viewers would stand.

The Mystery of Las Meninas: Hidden Riddles and Puzzling Paradoxes

The mystery of Las Meninas that has been debated for 360 years is: “What is being painted on the hidden side of the canvas?” (Carminati, 2012). There are three leading theories. The oldest theory is that Velázquez is painting a life-sized portrait of the Infanta. In this formulation, the King and Queen are passing through the studio to watch Velázquez painting their daughter, and the Queen’s chamberlain stands in the open doorway waiting to escort the royal couple back to their chambers. The faces of the King and Queen are reflected in the mirror on the back wall.

A second theory is that Velázquez is painting a portrait of the King and Queen. The Infanta and her retinue are stopping by to watch the royal parents sitting for the court painter. In this formulation advanced in 1981 by the art critic Leo Steinberg, the painted faces of the King and Queen are reflected from the canvas to the mirror (Steinberg, 1981). In 2009 two scientists, David Stork and Yasuo Furuichi, built a virtual 3-D computer graphic model of Las Meninas that permits the viewer to analyze the painting from any angle. Their results support the idea that the faces of the royal couple on the mirror originate from the painted faces on the hidden side of the canvas, not from the King and Queen watching Velázquez at work (Stork and Furuichi, 2009).

Other than the King and Queen, is there anything else that Velázquez is painting on the canvas? This bring us to a third theory, the most provocative of all: Velázquez is painting a picture of himself who is painting a picture of the painting that we and the King and Queen are looking at. The artist has created a deliberate ambiguity, tricking us into seeing the same picture twice. Is he telling us that art and life are both an illusion?

The art critic Blake Gopnik recently pointed out that the true subject of Las Meninas “is the heroic moment of its own making, recorded ‘live’ in a real place, as no history painting had ever been before.” Gopnik goes on to suggest that the title be changed to The Immaculate Reflection since the picture is an authentic mirror of nature itself like no other painting in the history of art (Gopnik, 2010).

Velázquez’s creation of Las Meninas with its hidden riddles and puzzling paradoxes brings to mind the famous quip of James Joyce, who when asked to explain the success of his novel Ulysses responded: “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.” (Ellmann, 1982).

Picasso Attempts to Solve the Mystery

By the James Joyce standard, Velázquez achieved immortality. Not only has Las Meninas kept the professors and art historians busy for more than 350 years, it also kept Pablo Picasso busy. In 1957 at age 75, Picasso secluded himself for five months in his studio, devoting full time to a radical deconstruction of Velázquez’s masterpiece. Picasso was determined to unearth its mystery by recasting Las Meninas in terms of his own contemporary cubist style (Refart i Planas, 2001). As Picasso was fond of saying, “Great artists don’t copy, they steal.”

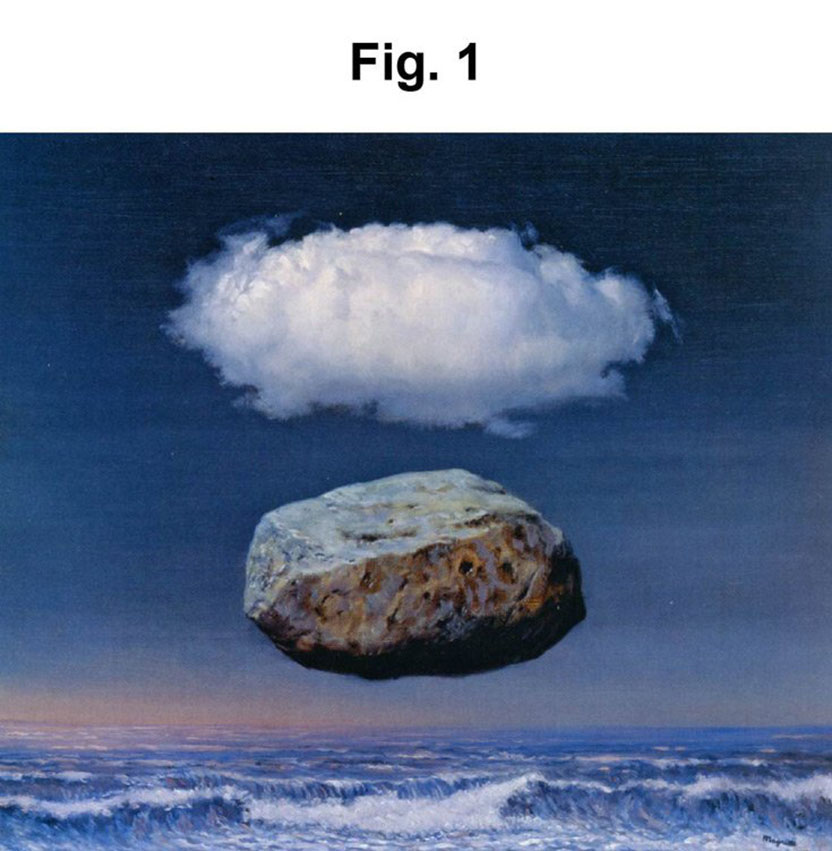

Picasso painted 46 different versions of Las Meninas. The entire series is on permanent display at the Picasso Museum in Barcelona. Picasso’s first version of Las Meninas is one of his largest canvases, 6.5 by 8.5 feet, second in size only to his Guernica. And like Guernica, Picasso’s first version of Las Meninas is painted in black and white and in a horizontal orientation (Figure 3). But the most radical change is the cubist rendition of the figures, which creates a chaotic scene, severing the perceptual connection between the figures in the painting and the viewers outside the pictorial space. We, as well as the King and Queen, are no longer right there in the room to watch the Infanta and the painter.

Figure 3. Las Meninas after Velázquez

Pablo Picasso (1957). Oil on canvas. 6.4 x 8.5 ft. Picasso Museum, Barcelona. © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In his typical imaginative style, Picasso injects several humorous touches. As a tribute to Velázquez, he enlarges the height of the painter, making him a towering figure whose double-profiled face reaches the top of the ceiling (Figure 3). The Chamberlain at the back of the room is given increased visibility as a shadow figure that is a symbolic representation of Picasso himself. The large dog in the original is replaced with a dwarfed dachshund, presumably to provide companionship for the dwarfed maid of honor.

Why did Picasso spend so much time on Velázquez’s masterpiece? Even though he soon realized that he could not solve the mystery of what is being painted on the hidden side of the canvas, he became obsessed with showing the world how Las Meninas might have looked had it been painted in 1957 rather than in 1656. Picasso believed that great art will always be great no matter when it was conceived. “To me, there is no past or future in art. If a work of art cannot live always in the present, it must not be considered at all.” In this sense, Picasso was subscribing to T. S. Eliot’s philosophy of great poetry. According to Eliot (1985), “The perpetual task of poetry is to make all things new (sic). Not necessarily to make new things.”

A Contemporary Puzzle-painting Inspired by Las Meninas

The latest artist “to make Las Meninas new” is the contemporary painter Kelly James Marshall. Marshall is widely acclaimed to be one of the leading African-American painters in the U.S. today. For the last 35 years, he has chronicled the African-American experience in a series of large narrative paintings that feature only black figures. The Metropolitan Museum recently sponsored a retrospective of Marshall’s work, featuring 72 of his large painting done over three decades (Alteveer, et al., 2016).

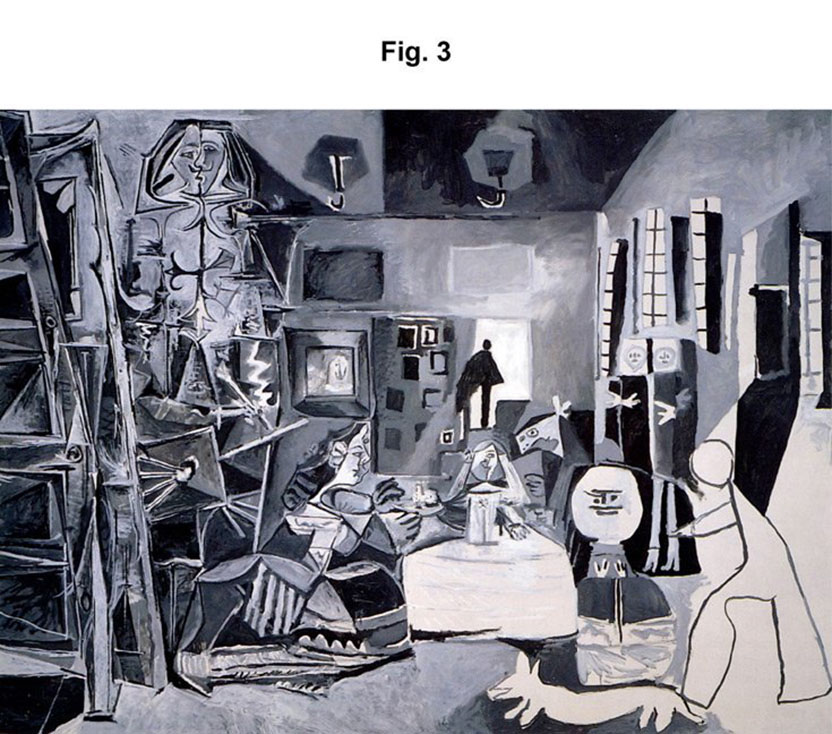

The highlight of this exhibit was a painting called Untitled (Studio), completed in 2014. Studio resembles Las Meninas in its composition, subject matter, and large size (7 by 10 feet) with life-sized figures (Figure 4). At first glance, Studio appears straightforward. At the center of the painting is a model with salmon-colored trousers who sits in front of a red backdrop. A woman in green high heels is adjusting the model’s head. At the left is an easel with an unfinished painting of the torso of the female model. In the background are two men, one behind the painting and the other behind the red backdrop. On the back wall are three open window panes reminiscent of the open door in Las Meninas. A yellow dog sits underneath the table.

Figure 4. Untitled (Studio)

Kerry James Marshall (2014). Acrylic on PVC panel. 7 x 10 ft. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

On second viewing, things in Studio are not so straightforward. The mystery here is not what is being painted on the canvas, but where and who is the artist (Figure 4). Is it the man behind the red backdrop who is putting a yellow jacket over his arm? Or is it the shadowy, nude male figure standing behind the easel? Or is it the woman in the green high heels with the paint-smeared dress whose gaze is directed outside the pictorial space. Is she looking out at a mirror to help her adjust the model’s profile? Or is she looking for confirmation from the artist who is outside the frame? Or maybe her gaze is meant for us, the viewers, who would be standing in the same place as the artist?

Marshall has created a puzzle-painting that is provocative, complex, and subject to different interpretations much like Velázquez’s Las Meninas. Studio differs from Las Meninas in several ways. The visual illusion of depth in Las Meninas is missing in Studio where the figures and objects appear flat. Marshall’s focus is not on perspective; it is on color. All the figures except for the dog are jet black, and this blackness heightens the intensity of the reds, the yellows, the blues, and the salmon color of the model’s trousers. By focusing on color through his literalization of blackness, Marshall has achieved originality in the same way that Velázquez did with perspective and Picasso with cubism.

2017 Lasker Awards: Solving Puzzles That Advance Biomedical Science and Public Health

Unlike Velázquez, Picasso, and Kelly James Marshall who created puzzles that stimulate the imagination, this year’s Lasker Basic and Clinical Awardees solved puzzles that advance the biomedical sciences. This year’s Public Service Awardee has advanced the health of women throughout the world for 100 years.

The Lasker Basic Research Award honors Michael N. Hall (University of Basel) for his discoveries concerning the nutrient-activated TOR proteins and their central role in the metabolic control of cell growth. Hall’s original work, carried out in the late 1980s, began as a genetic analysis of how the immunosuppressant drug rapamycin inhibits the growth and survival of yeast cells. The result was the identification of TOR (target of rapamycin) and the two TOR complexes, TORC1 and TORC2. Hall’s discovery of what at the time was a novel class of kinases laid the foundation for the current explosion in the mTOR field in which scientists soon identified the single mammalian orthologue of the two yeast TORs and elucidated the upstream and downstream mechanisms of TOR signaling. These studies revealed how mammalian cells use mTORC1 as a molecular integrator that senses multiple signals arising from growth factors, hormones, amino acids, and oxygen status. Once activated, mTORC1 regulates pathways required for cell proliferation and growth, involving the synthesis of proteins, lipids, and nucleotides. Research on TOR has also paved the way for the recent development of mTOR inhibitors to treat certain forms of cancer and has shed light on understanding mechanisms involved in the control of blood glucose and the aging of cells.

The Lasker~DeBakey Clinical Research Award honors two scientists, Douglas R. Lowy and John T. Schiller (National Cancer Institute, NIH), for technological advances that enabled development of HPV vaccines for prevention of cervical cancer and other tumors caused by human papillomaviruses. The identification of HPV as the infectious agent responsible for cervical cancer in the early 1980s by Harald zur Hausen (Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine, 2008) provided a strong stimulus for research that would lead to an HPV prophylactic vaccine. In 1992, Lowy and Schiller published two observations that stood the test of time: 1) the L1 major structural protein of papillomaviruses (produced as a recombinant protein in insect cells) could self-assemble into non-infectious virus-like particles (VLPs) without the need for other viral proteins, and 2) such L1 VLPs possessed the ability to induce high-titer neutralizing antibodies. Moreover, in 2001 Lowy and Schiller, in collaboration with scientists at Johns Hopkins University, carried out the first phase I clinical trial of an HPV VLP vaccine containing the L1 VLP from type 16 HPV, which is the most common cause of cervical cancer. The vaccine, which was given to 36 normal volunteers, was well tolerated, proved safe, and was highly immunogenic in all subjects.

The aforementioned pioneering findings were followed by innovative contributions from scientists at Merck & Co. and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), who developed the first commercially available prophylactic L1 HPV vaccines. These vaccines were approved by the FDA for human use in 2006 (Merck) and 2009 (GSK). Since 2006, approximately 50 million women worldwide have been vaccinated. In the U.S. ~60% of adolescent girls and ~50% of adolescent boys have received one or more doses of the three-dose HPV vaccine series.

The Lasker~Bloomberg Public Service Award honors Planned Parenthood for providing health services and reproductive care to millions of women. Planned Parenthood, which began as a birth control clinic in 1916, is now a vibrant international organization. In addition to providing contraceptive services, it provides examinations and testing for breast and cervical cancer, testing and treatment for sexually-transmitted diseases, pregnancy testing, and sex education and counseling.

REFERENCES

Alteveer, I., Molesworth, H., Roelstroete, D., and Winograd, A. (2016). Kerry James Marshall: Mastry (New York: Skira Rizzoli)

Carminati, M. (2012). Velazquez’s Las Meninas: Art Mysteries (Milan: Ore Cultura S.R.L.)

Eliot, T.S. (1985). Tradition and the practice of poetry with an introduction and afterword by A. Walter Litz. The Southern Review 21, 873-888 (This article is a typescript of the Dublin Lecture delivered by Eliot at University College, Dublin on January 24, 1936)

Ellmann, R. (1982). James Joyce. (New York: Oxford University Press). Revised Edition, p. 521

Rafart i Planas, C. (2001). Picasso’s Las Meninas (Barcelona: Editorial Meteora)

Steinberg, L. (Winter, 1981). Velázquez’ “Las Meninas”. October. 19, 45-54