by Joseph L. Goldstein

The Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, famous for his geometric grid paintings, was an ardent jazz fan. In the late stage of his career, he became intrigued with boogie-woogie music, which inspired him to paint his masterpiece Broadway Boogie Woogie. While boogie-woogie and science operate in different domains, both share the characteristics of experimentation, improvisation, and pushing boundaries—whether it is creating new piano rhythms and melodies or creating new ways to discover innovative solutions to problems in art and science.

Few artists can claim as central a place in the history of 20th-century art as the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872 to 1944). In the 1920s, Mondrian pioneered the evolution of painting from figuration to pure abstraction. Many art historians regard him as the most radical and innovative abstract artist of the modern era (1, 2).

Mondrian’s Geometric Abstractions: Grid-Like Art with Colors

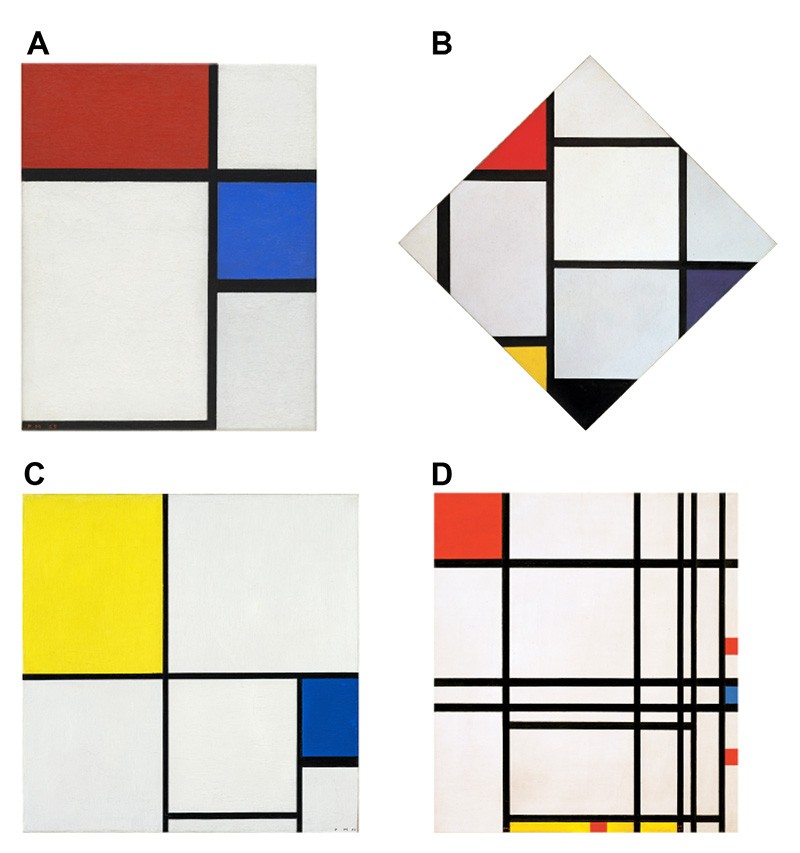

Mondrian is best known for his signature style consisting of black horizontal and vertical lines arranged asymmetrically on a white background with colored squares and rectangles painted in the primary colors of red, blue, or yellow (Fig. 1 A–D). The simplicity of Mondrian’s grid-like compositions with their exquisite sense of asymmetrical balance evokes a sense of elegance, order, and beauty.

Fig 1. Examples of Piet Mondrian’s early abstract paintings. Oils on canvas. (A) Composition No. 11 (1929). 15 7/8 × 12 5/8 in. Museum of Modern Art, New York City, 486.41. (B) Tableau No. IV (1924-1925). overall (diamond): 56 1/4 × 56 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Gift of Herbert and Nannette Rothschild, 1971.51.1. (C) Composition with Yellow and Blue (1932). 21 7/8 × 21 7/8 in. Fondation Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland, 78.3. (D) Composition No. 8 (1939 to 1942). 29 1/2 × 26 3/4 in. Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, AP 1994.05. Image credit: ©2024 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust.

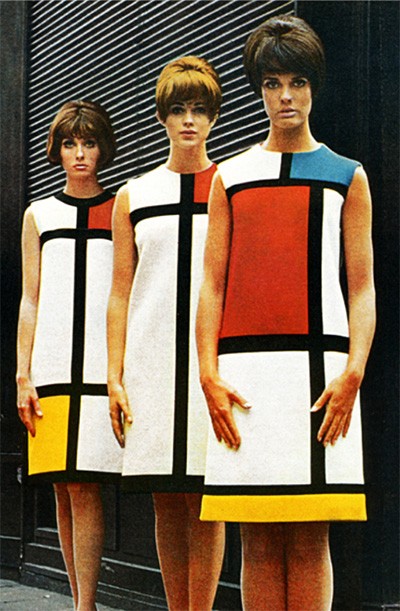

Fig. 2. Yves Saint Laurent, Three Dresses from 1965 to 1966 Couture Collection. Life Magazine. 59, September 3, 1965, p. 46. Image credit: Joseph Leombruno and Jack Bodi (3), (photographers).

Over the course of 25 years from 1919 to 1944, Mondrian painted several hundred abstract compositions, each with a different arrangement of squares and rectangles rendered in different primary colors. His simple geometric shapes and limited color palette have become a vibrant part of our popular culture (3). In the fashion industry, Mondrian’s signature style is evident in the haute couture of Yves Saint Laurent (i.e., the iconic “Mondrian dress”) as well as in everyday streetwear (Fig. 2). His abstract approach has also significantly influenced other areas of popular culture, including graphic design, interior design, advertising, and architecture.

Mondrian’s Influence on Calder: Invention of the Kinetic Sculpture

In the art world, the unique environment of Mondrian’s Paris studio sparked a profound change in the art of Alexander Calder (1898 to 1976), the American sculptor who invented the “mobile,” a type of kinetic sculpture in which the suspended elements move and interact with each other when touched or exposed to air currents (4, 5). Several years after graduating from college in 1919, Calder moved to Paris in 1926 where he developed his radical work of performance art Cirque Calder in which models made of wire and a spectrum of found materials were created to perform the functions of various circus performers.

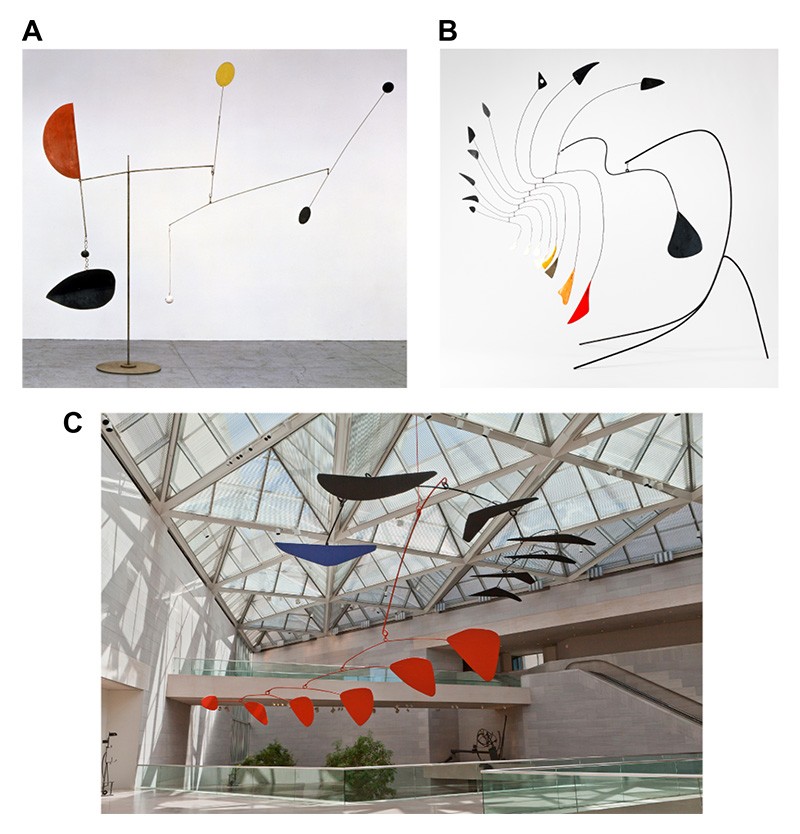

In 1930, Calder visited Mondrian’s Paris studio, an experience he described as one that “gave me the shock that converted me” (5). He immediately suggested to Mondrian that his colored cardboard rectangles tacked to the wall would be more interesting if they could be made to move back and forth in space. Mondrian replied: “No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast” (5). The speed Mondrian referred to was the rapidity at which the eye perceives the squares—a red square and a blue square—as a dynamic relationship. Within several weeks, Calder had produced a series of abstract paintings, and within a year, he made his first mobiles, the world’s first kinetic sculptures (Fig. 3 A–C).

Fig. 3. Examples of Alexander Calder’s mobile sculptures. (A) Steel Fish (1934). Sheet metal, wire, rod, and paint. 115 × 137 × 120 in. Calder Foundation, New York. (B) Little Spider (1940). Painted sheet metal and wire. 44 × 50 × 55 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Klaus G. Peris. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 1966.120.18. (C) Untitled (1976). Aluminum and steel. 358 × 912 in; gross weight, 920 lb. Mobile sculpture in atrium of East Wing, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Gift of the Collectors Committee. All works by Alexander Calder © 2024 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Image credit: (A) Photo courtesy of Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York; (B) National Gallery of Art; (C) B. Christopher/Alamy, Inc. Stock Photo.

Over the next 45 years, Calder’s work evolved to include monumental sculptures that are exhibited in museums and in outdoor public spaces throughout the world (4, 5). Calder’s invention of the mobile inaugurated a new epoch in the history of sculpture in the same way that Mondrian’s invention of geometric abstractions inaugurated a new epoch in painting. How can one explain the remarkable creativity of these two giants of art? To paraphrase the Irish poet and wit Oscar Wilde, people become creative when they let their minds misbehave (6).

Boogie-Woogie Jazz: A New Inspiration for Mondrian

Speaking of misbehaving minds and creativity brings me back to Mondrian and to a new phase in his career. This new phase began in 1940 when Mondrian moved from Europe to New York City to escape the rise of Nazism (1). Here, in New York, he was inspired by the city’s frenetic lifestyle and bustling energy. On his very first night in Manhattan, the 68-year-old artist, an avid jazz nut who listened to records while painting, insisted on going to a concert to hear the jazz pianist Albert Ammons (7).

Fig. 4. Albert Ammons, shown in 1945 wearing one of his trademark pinstriped suits. Photo: Sammie Ellis. Image credit: Reproduced with permission from Pianorarescores.com.

In the 1930s and 40s, Ammons (Fig. 4) was a leading figure in the development and popularization of boogie-woogie music (8, 9). In 1949, he received an honorary degree of Doctor of Jazz from Columbia University, and in the same year, he was invited to perform at President Truman’s presidential inauguration (10). Unfortunately, Ammons’ career ended abruptly at age 42 at the peak of his powers when he died suddenly of unknown cause.

Boogie-woogie music originated in the African American communities of the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It had its roots in the repetitive chants of the Black work gangs as they sang to relieve the monotony of laying railroad tracks (9). After the Civil War, many emancipated slaves migrated to cities of the North and Midwest to find better living conditions. Chicago, in particular, became the place where the chants of the work gangs evolved into a unique piano form of music in which the piano players created repetitive bassline rhythms with their left hand, while improvising and embellishing more melodic rhythms with the right hand (11). Even though the player’s left hand and right hand seemed to ignore each other, the combined finger action produced an exuberant rhythm called “syncopation”—the defining feature of boogie-woogie jazz. Syncopation involves the sudden shift in beats in the music such that strong beats become weak and weak beats become strong. The complexity of this effect creates utter surprise and encourages unbridled joy and vigorous dancing (9, 11).

Boogie-woogie reached its peak popularity in large part through a series of Carnegie Hall concerts titled From Spirituals to Swing in 1938 and 1939. Ammons—the boogie-woogie stylist whom Mondrian would see upon his arrival in New York—played at the 1938 concert along with musicians from folk, jazz, and spiritual traditions who were in the process of reinventing American music. The Carnegie Hall concerts enthralled the mostly white audiences, introducing them to a new style of music that became the craze of Manhattan (9, 11).

Fig. 5. Piet Mondrian. Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942 to 1943). Oil on canvas. 50 × 50 in. Museum of Modern Art, New York, 73.1943. Image credit: ©2024 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust.

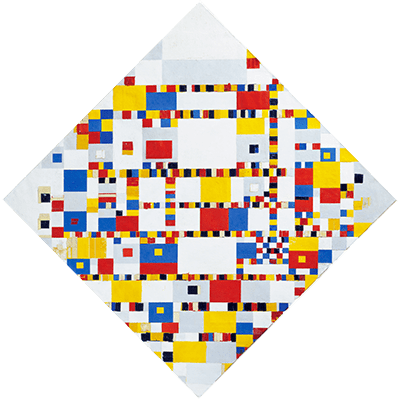

Fig. 6. Piet Mondrian. Victory Boogie Woogie (unfinished) (1942 to 1944). Oil, pencil (drawing and writing equipment), paper, charcoal, adhesive tape, on canvas. 49 5/8 × 49 5/8 in; vertical axis, 70.5 in. Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, Netherlands, 0810747. Image credit: ©2024 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust.

Mondrian in Motion: Painting Broadway Boogie Woogie

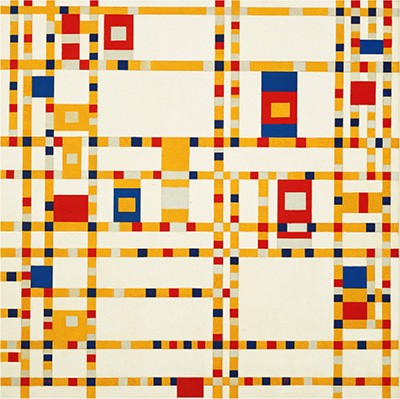

Mondrian’s love of boogie-woogie music, together with his fascination with the grid layout of the streets in midtown Manhattan and with the dynamic energy and lights of Broadway, inspired him to create his most famous work Broadway Boogie Woogie, painted in 1942–43 (Fig. 5). In this work, he uses his characteristic grid structure, but instead of the black vertical and horizontal lines as in his earlier work, his grid now became a series of yellow lines studded with small square dots of red, gray, and blue. Mondrian may have intended the colored dots on the yellow grid as symbols for boogie-woogie music flowing out of the jazz clubs in Times Square or for taxis and autos moving down the crowded streets in midtown Manhattan (1, 7, 12). Broadway Boogie Woogie resides in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. It is one of the most innovative paintings in the 20th century and has become an iconic masterpiece of modern art.

Mondrian painted his last work, Victory Boogie Woogie, just before he died in 1944 (Fig. 6). He chose the title in anticipation of the end of World War II (1, 13). Victory Boogie Woogie differs from the earlier Broadway version in terms of the flow of the movements of the painted squares and dots along the yellow grid. Instead of the flowing movements in Broadway, a more syncopated movement predominates in Victory, reflecting the swarming of Manhattan’s grand buildings, its busy street intersections jammed with traffic, and the wild rhythm of the boisterous boogie-woogie music emanating from its many jazz night clubs. The composition of Victory is more complex than that in any other of Mondrian’s hundreds of paintings (13). Its tightly packed grids, diversity of geometric shapes, and density of colors push the boundaries of his signature style. Victory evokes a sense of both order and chaos at the same time—a testament to Mondrian’s innovative approach to art.

Boogie-Woogie Jazz: A Template for Creative Science

In the 1940s, boogie-woogie pianists were creating a stir in the musical world, upending traditional approaches to rhythm and melody with the imagination and energy of adventurous explorers. Rooted in jazz and driven by improvisation, the boogie-woogie sound, with its churning bass and catchy melody, became foundational for other genres of music popularized in the postwar period like rock and roll, gospel, and rhythm and blues (9, 11). Given his long-standing love of jazz and as someone who prided himself in recognizing creativity, Mondrian appreciated the inventive musicality and accomplishments of the boogie-woogie pianists.

The domains of boogie-woogie and science would seem to have nothing in common. Yet, both are examples of the phenomenon of adaptive creativity, which is a form of problem-solving based on the triad of experimentation, improvision, and pushing boundaries (14). In much the same way that boogie-woogie pianists nimbly explore various left-hand, right-hand maneuvers in order to create peppy rhythms that lead to new melodies, biomedical scientists explore various methods and ideas that lead to novel solutions to complex problems.

Boogie-woogie influenced the creative trajectory of modern jazz piano masters like Duke Ellington, Oscar Peterson, and Art Tatum (11), and its playful approach to asymmetric syncopation was taken up by the guitarists, drummers, and horn players whose music populates the Billboard charts to this day. In a similar sense, the creative aspects of scientific inquiry continually undergo change and evolution—influenced and driven by the societal needs of the time. The rapid development of effective vaccines for polio and SARS-CoV-2 are striking examples of creative science in action.

Of all the metaphoric ways that science resembles boogie-woogie, perhaps the most consequential is the curiosity and passion of the imaginative pianists and scientists whose original accomplishments are essential for pushing new boundaries in their respective fields of music and science—another example of Oscar Wilde’s misbehaving minds that produce innovation.

2024 Lasker Awards: The Boogie-Woogie Approach

As described above, the classic boogie-woogie jazz pianists of the 1930s and 40s created peppy rhythms and spirited new melodies through a triad of experimentation, improvisation, and pushing new boundaries. A similar triad underlies the discoveries and advances of this year’s Lasker winners. For a detailed account of this year’s Lasker Awards, please refer to the descriptions of the Basic, Clinical, and Public Service Award pages on this website. A brief summary of the awards appears below.

Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award. The recipient of this year’s award is Zhijian “James” Chen (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas) for his discovery of the cGAS enzyme that senses foreign and self-DNA, solving the 100-year-old mystery of how DNA stimulates immune and inflammatory responses. When DNA binds to cGAS, the enzyme becomes activated and catalyzes the synthesis of a unique dinucleotide, cyclic 2′, 3′-GMP-AMP (cGAMP). The cGAMP messenger binds and activates the adaptor protein STING, which turns on a signaling cascade that culminates in the activation of an array of genes that leads to the synthesis of immune and inflammatory cytokines, including type-1 interferons. Inasmuch as increased interferons occur in autoimmune diseases such as lupus, Chen’s research has opened new approaches for developing small molecular inhibitors of cGAS designed to lower the inflammatory cytokines that underlie lupus and other diseases.

Lasker~DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award. The recipients of this award are Joel Habener (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston); Svetlana Mojsov (The Rockefeller University, New York City); and Lotte Bjerre Knudsen (Novo Nordisk, Maaloev, Denmark). The awardees are recognized for their discovery and development of GLP-1-based drugs that have revolutionized the treatment of obesity. In 1982, Habener reported the cloning of the glucagon gene and determined that it encoded a precursor protein that contains, in addition to glucagon, a second 37-amino acid peptide that resembles glucagon and is referred to as GLP-1 (1-37). Using chemically synthesized peptides, Mojsov showed that a processed version lacking the first six amino acids, referred to as GLP-1 (7-37), is the physiologically active form of the hormone that stimulates insulin secretion from the pancreas. In the early 1990s, Lotte Bjerre Knudsen became intrigued with the idea that GLP-1 (7-37) could be modified to treat obesity, leading her to head a team at Novo Nordisk that turned GLP-1 (7-37) into two weight-loss promoting drugs, liraglutide (Saxenda®) and semaglutide (Wegovy®). The key to Novo Nordisk’s success in developing these drugs is the attachment of a long-chain fatty acid via a linker to a single residue in GLP-1 (7-37). The two drugs differ in their type of fatty acid and linker attachment. The more potent of the two drugs is Wegovy®, which is administered weekly by subcutaneous injection. Clinical trials have shown that Wegovy® reduces body weight by as much as 15% when studied over a 16-month period. Since its FDA approval in 2021, more than one million people in the United States have received prescriptions for the drug.

Lasker~Bloomberg Public Service Award. The recipients are Salim S. Abdool Karim and Quarraisha Abdool Karim (CAPRISA, Durban, South Africa and Columbia University, New York City). This husband and wife team are being honored for their establishment in 2002 and visionary leadership of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa. By successfully integrating science with policy, the Abdool Karims have built a vibrant scientific infrastructure in South Africa that has played a pivotal role in the successful prevention and treatment of HIV, focusing on the vulnerabilities of young women by treating them with antiretroviral drugs to prevent sexually transmitted HIV infection. CAPRISA has also developed effective protocols for treating patients coinfected with tuberculosis and HIV.

1. Y.-A. Bois, J. Joosten, A. Z. Rudenstine, H. Janssen, Piet Mondrian: 1872–1944 (Leonardo Arte, Milan, 1994).

2. A. Moszynska, Abstract Art (Thames & Hudson, London, 2020).

3. N. J. Troy, A. M. Tartsinis, Mondrian’s Dress: Yves Saint Laurent, Piet Mondrian, and Pop Culture (The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2023).

4. M. Prather, A. S. L. Rower, A. Pierre, Alexander Calder, 1898–1976 (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1998).

5. J. Perl, Calder: The Conquest of Time: The Early Years: 1898–1940 (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2017), pp. 338–348.

6. O. Wilde, R. Keyes, The Wit and Wisdom of Oscar Wilde: A Treasury of Quotations, Anecdotes, and Repartee (HarperCollins, New York, 1996).

7. T. Lloyd, New York Style in Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie. Singulart Magazine, 31 October 2019, pp. 1–9. Accessed 1 June 2024.

8. C. I. Page, Boogie Woogie Stomp: Albert Ammons and His Music (Northeast Ohio Jazz Society, Cleveland, 1997).

9. P. J. Silvester, The Story of Boogie-Woogie: A Left Hand Like God (Scarecrow Press Inc, Lanham, 2009).

10. A. C. Ammons, Obituary: Jazz Pianist, is dead. New York Times, 4 December 1949, p 42. Accessed 1 June 2024.

11. T. Gioia, The History of Jazz (Oxford University Press, New York, ed. 3, 2021).

12. L. Dickerman, Mondrian’s Boogie Woogie. October Magazine, vol. 185, pp. 118–138 (1 August, 2023), 10.1162/octo_a_00496. Accessed 1 June 2024.

13. M. von Bommel, R. Spronk, H. Janssen, Eds., Inside Out Victory Boogie Woogie: A Material History of Mondrian’s Masterpiece (Amsterdam University Press, 2002).

14. K. H. Kim, R. A. Pierce, “Adaptive creativity and innovative creativity” in Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship, E. G. Carayannis, Ed. (Springer-Verlag, 2013), pp. 35–40.