Franz-Ulrich Hartl

Arthur Horwich

The Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health

The Art of Science

Opening remarks by Joseph Goldstein

The card players of Caravaggio, Cézanne and Mark Twain: Tips for getting lucky in high-stakes research

An expanded version of these remarks originally appeared in Cell.

To the scientist, the thrill of discovery is like the thrill of a royal flush to the poker player. Scientists who receive Lasker Awards and Nobel Prizes share many things in common with poker superstars, both of whom take risks and gamble for high stakes. Scientists pit their wits against Nature’s puzzles, betting that their efforts will ferret out those rare nuggets of truth embedded in a vast mountain of artifacts. Poker players pit their wits against mathematical probabilities, wrestling with the indisputable fact that a deck of 52 cards can be shuffled into 52! sequences, which is 52 x 51 x 50 x 49 and so on down to 1, which comes to 8.1 x 1067 possible card permutations, a humongous number — 53 orders of magnitude greater than the 1014 synaptic connections in the human brain and 45 orders of magnitude greater than the 1023 stars in the universe.

Philosophers of science have paid little attention to the relative roles of luck vs. skill. But in card-playing circles, the luck vs. skill question has been debated for hundreds of years. Some of the best insights come not from card-playing experts, but from artists such as Caravaggio and Cézanne and from writers like Mark Twain.

Caravaggio’s Cardsharps

Figure 1. (a) Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi). The Cardsharps, c. 1594. Oil on canvas, 94.2 x 120.9 cm. Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth. (b) Georges de La Tour. The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs, late 1620s. Oil on canvas, 97.8 x 156.2 cm. Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth.

In the late 1300s when card playing first became a popular form of entertainment in Italy and France, card cheats and crooked gamblers dominated the game, minimizing the skill factor of the player. This state of affairs is wonderfully captured in The Cardsharps, a painting done in 1594 by the Italian artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, known today as Caravaggio (Fig. 1a). Art historians consider The Cardsharps to be the most influential gambling-theme painting in the history of art. The composition is simple and elegant. An innocent-looking young man has been lured into a card game by a middle-aged sinister man whose fingers signal to his young accomplice, who holds the 5 of hearts tucked in his belt behind his back. The object of the conspiracy — a stack of coins — sits at the edge of the table.

Caravaggio’s genius is his creation of a dramatic scene of concealment in which all three characters are hiding something. The tension and drama are heightened by many details, including the split glove that allows the older man to easily feel the marked cards, the black hat of the innocent boy that hides the peering right eye of the older man, and the older man’s left hand that comes out of nowhere and arrives close to the younger cardsharp’s dagger. The whole scene keeps the viewer on tenterhooks: any slight chance movement might reveal the trickery. The young boy may be skillful at his game, but we’ll never know — he’s the victim of bad luck.

The Cardsharps inspired many artists to take up the gambling theme. One famous imitation is the painting entitled The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs, done in the late 1620s, by the French artist Georges de la Tour (Fig. 1b). In dazzling colors, de la Tour depicts the dangers of wine, women, and gambling. Here we see a trio of conniving cheats, highlighted by carefully orchestrated gazes and gestures. Is the gaze of the woman with the plunging neckline intended for the maid servant to give her more wine or is she signaling the cheat to play the Ace of Clubs?

Cézanne’s Card Players

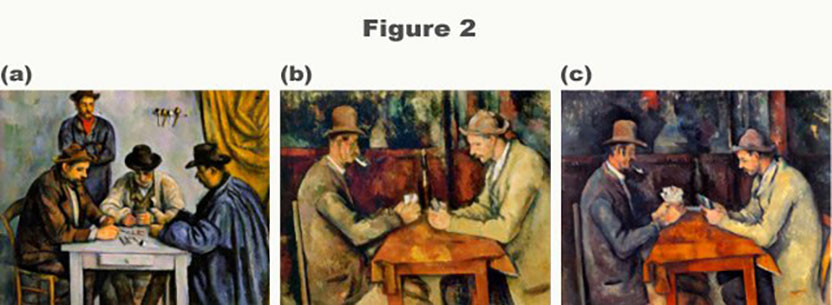

Figure 2. Paul Cézanne. The Card Players. Three of the five versions of this series are shown: (a) c. 1890-92. Oil on canvas, 65.4 x 81.9 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. (b) c. 1892-96. Oil on canvas, 47 x 56 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. (c) c. 1892-96. Oil on canvas, 60 x 73 cm. The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Caravaggio’s celebrated compositional portrayal of trickery, greed, and lust proved so seductive and powerful that it continued to be copied by artists for 300 years. Then, in the 1890s, Paul Cézanne reinvented the card-playing theme in a revolutionary way. Over a 5-year period, Cézanne executed five paintings of male peasants playing cards. Known as The Card Players, the five paintings in the series (three of which are shown in Fig. 2) vary in size and scale, but all are formally based on a similar composition: 2 to 5 stone-faced, drably dressed, stocky men — all wearing unadorned hats — are depicted playing cards and smoking clay pipes while gathered around a plain table. The men look down at their cards rather than at each other; they are totally and intensely absorbed in the ritual of their game — “a kind of collective solitaire” in the words of the art critic Meyer Schapiro. The tense atmosphere of concentration and solemnity is accentuated by the shades of brown and blurs of blue.

The contrast between the card players of Caravaggio and Cézanne is striking. Unlike Caravaggio’s masterpiece, Cézanne’s seminal series depicts no cheating, no money on the table, no melodrama, no skullduggery, no extravagant clothes. Cézanne is telling us in no uncertain terms that card play is no laughing matter. The key to skillful play and winning is focus, focus, focus. Luck is not necessary when there are no distractions and no trickery of the Caravaggio type.

As to which is more important, luck or skill, Caravaggio leans toward luck and Cézanne favors skill.

Mark Twain’s “Science vs. Luck”

To settle the argument, there is no one better to turn to than America’s greatest humorist and arguably most creative fiction writer — Mark Twain. Twain was an unabashed lover of poker and was saddened by how few people in the US knew anything about the game, lamenting “I have known clergyman, good men, kind-hearted, liberal, sincere, and all that, who did not know the meaning of a ‘flush’. It is enough to make one ashamed of one’s species.” In 1870, Twain wrote an essay entitled “Science vs. Luck” about a fascinating court case in Kentucky in which a dozen school boys were arrested for playing poker for money. Back then, many states had strict laws prohibiting games of chance, and even at enlightened institutions of higher learning, such as Harvard University, errant students incurred the heaviest fines — not for drinking or fighting, but for playing cards.

The lawyer hired to defend the 12 poker-playing boys in Twain’s essay came up with an ingenious defense: poker was not a game of chance, and thus his clients could not be punished until it was proven that poker was a game of chance. To make a short story even shorter, the witnesses against the boys (who were all deacons of the Church) testified that poker was all luck, whereas the lawyer’s witnesses testified in favor of skill. The judge was unable to render a decision, and in his paralyzed state he called upon the lawyer to suggest a solution. The lawyer quickly replied: “Impanel a Jury of six of each, Luck vs. Science. Give them candles and a couple of decks of cards. Send them into the jury-room, and just abide by the results.” Six deacons were sworn in as the “Chance” jurymen, and six who were experienced poker players were the “Science” jurymen.

After one day of deliberation, the foreman of the jury — one of the deacons — read the verdict: “We, the Jury in the case of the Commonwealth of Kentucky vs. John Wheeler, et al. have carefully considered the points of the case and do hereby unanimously decide that the game is eminently a game of Science and not of Chance. In support of our verdict, we call attention to the fact that the Chance men are all busted; and the Science men have got the money.” The judge declared the Chance theory a pernicious doctrine and then ruled that poker playing was no longer a punishable offense in the state of Kentucky.

I am sure that most of you are not convinced that Mark Twain’s literary experiment settled the question of Luck vs. Skill. Fortunately, the first convincing scientific experiment on the subject was recently carried out by the University of Chicago economist Steven Levitt. Levitt is the author of the best-selling book Freakonomics, which reveals how the tools of economic research can be used to study relationships that underlie events and problems that all of us encounter every day. Several representative examples that Levitt tackles in his book: “Which is more dangerous, a gun or a swimming pool?” “Why do drug dealers still live with their moms?” “What do school teachers and sumo wrestlers have in common?”

Levitt’s new study, called ‘Pokernomics’, analyzed the performance of 32,000 players who took part in the 2010 World Series of Poker in Las Vegas. Levitt divided the players into two groups — a highly skilled group and an ordinary group. The highly skilled group consisted of 720 players — 2.3% of the total — who won the most money in 2009 tournaments. The ordinary group comprised the rest of the 32,000 — 97.7% of the total. In the 2010 World Series, the skilled poker players made a return on investment of 30%, whereas the ordinary players had a loss of 15%. This large gap in return is strong evidence that poker as it is played today is a game of skill and not luck.

The luck factor in high-stakes research

Do scientists who win Laskers and Nobels produce award-winning research because they are luckier than other scientists? Is luck more important than skill in high-stakes research? Quantifying the luck vs. skill factor in research is not so straightforward as in the case of Levitt’s Pokernomics. But I think one can come up with a reasonable assessment, depending on one’s definition of luck, i.e., whether one is referring to blind luck or insightful luck. Blind luck is when a person en route to the Lasker Luncheon gets on the elevator at the Pierre Hotel, finds a lottery ticket on the floor of the elevator, and wins $10 million. Insightful luck is when the same person, en route to the Pierre, stops at the corner kiosk, buys a lottery ticket, and wins $10 million.

Blind luck is basically irrelevant to scientific discovery, but insightful luck is not. The person who purchases a lottery ticket has positioned himself or herself to win a prize. Whether or not he or she wins is a matter of mathematical probabilities. The same can be said for insightful scientists who purchase their skills by doing experiments, making observations, reading the literature, and keeping the right company — by which I mean going to the right meetings and associating with people smarter than yourself. Such a scientist has deliberately positioned and prepared himself or herself to be a strong candidate for good fortune. He or she is discovery prone — discovery prone in the sense of Louis Pasteur famous dictum: “Chance favors the prepared mind.”

The driving force that moves a scientific field in a new direction is the unexpected result — the surprise finding. The highest achievements in science come from skilled and prepared-of-mind individuals who can recognize the surprise result, act on it, and follow it wherever it leads.

There is no better example of the benefits of a prepared mind than the story of the invention of the microwave oven. In 1946, an electrical engineer and physicist named Percy Spencer at the Raytheon Company in Waltham, MA, visited a lab where magnetrons, the power tubes of radar sets, were being tested. Suddenly, he felt a chocolate peanut candy bar begin to melt inside his shirt pocket. According to Raytheon history, Spencer immediately sent a messenger boy to fetch a package of popcorn kernels. When Spencer held the kernels near the magnetron, popcorn exploded all over the room. Nine years later, in 1955, the first home microwave ovens were sold by Raytheon, and in 1999 Spencer was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Spencer was not the first person to notice that microwaves generate heat, but he was the first to think of using their heat to cook food.

Spencer was a man with restless curiosity and an intense passion to explore every wonder in the world. He clearly had skill and the itch to discover. But did he have luck? Spencer created his own luck by eating candy bars. What if he had been overweight and on a strict Atkins-like diet? Then he would have had bad luck, as would Raytheon stockholders, not to mention all the couch potatoes in the world!

All lucky scientists that I know have a common phenotype: they are excessively inquisitive, passionate, persistent, and have the uncanny instinct to be at the right place at the right time. And like Percy Spencer, they have the skills they need to create their own luck. To repeat Samuel Goldwyn’s dictum: “The harder I work, the luckier I get.” But the last word, as always, belongs to James Watson of DNA fame: “I was very, very lucky. But you know, they give prizes for people who are lucky.”

After lunch, you will hear the stories of this year’s “very, very lucky” Lasker awardees. The Basic Award will be presented by Titia de Lange, Professor at The Rockefeller University and a member of the Lasker Jury for the past 7 years. In our Jury deliberations, Titia is both Caravaggesque and Cézannish, giving equal weight to luck and science. The Clinical Award will be presented by Lucy Shapiro, Professor at Stanford University School of Medicine. Lucy, who has been a member of the Lasker Jury for two years, made her debut here last year with such a marvelous presentation that she is back again by popular demand. The Public Service presentation will be made by Harvey Feinberg, President of the Institute of Medicine and Chairman of the Jury for selecting the Public Service Award.

Medical Research Awards Jury

2011 Lasker Medical Research Awards Jury

First Row, left to right: J. Michael Bishop, University of California, San Francisco ● Paul Nurse, The Royal Society ● Lucy Shapiro, Stanford University ● Joseph Goldstein, Chair of the Jury, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center ● Cornelia Bargmann, The Rockefeller University ● Donald Ganem, Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research ● Diane Mathis, Harvard University

Second Row, left to right: Huda Zoghbi, Baylor College of Medicine ● Richard Lifton, Yale University ● Charles Sawyers, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center ● Titia de Lange,The Rockefeller University ● Robert Horvitz, Massachusetts Institute of Technology ● Eric Kandel, Columbia University ● Michael Brown, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center ● Martin Raff, University College London ● Günter Blobel, The Rockefeller University

Third Row, left to right: Marc Tessier-Lavigne, The Rockefeller University ● Jeremy Nathans, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine ● Jack Dixon, Howard Hughes Medical Institute ● Phillip Sharp, Massachusetts Institute of Technology ● Stanley Cohen, Stanford University● Craig Thompson, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center ● Stuart Kornfeld, Washington University ● Gregory Petsko, Brandeis University

Public Service Award Jury

George Alleyne, Pan American Health Organization ● Faith Hochberg, United States District Court for the District of New Jersey ● Harvey Fineberg, Chair of the Jury, Institutes of Medicine ● Susan Okie, Georgetown University ● John Edward Porter, Hogan Lovells US ● Enriqueta Bond, QE Philanthropic Advisors ● Haile Debas, University of California Global Health Institute ● Elias Zerhouni, Sanofi

Ceremony

-

Franz-Ulrich Hartl, Tu Youyou, Arthur Horwich, John Gallin

-

Joseph Goldstein speaks on art and science

-

New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg

-

Arthur Horwich and Lucy Shapiro

-

Franz-Ulrich Hartl

-

Jack Dixon, Joan Choppin, Purnell Choppin, Maria Freire

-

Louis Miller, Tu Youyou, Anthony Fauci, Xinzhuan Su

-

Francis Collins, Michael Bloomberg

-

Jan Vilcek, Ellis Rubinstein, Dinshaw Patel, Marica Vilcek

-

Michael Brown, Alfred Sommer

-

Alfred Sommer, Sue Desmond-Hellmann, William Haseltine

-

Barry Coller, Allen Spiegel

-

Adel Mahmoud, Purnell Choppin, Joan Choppin

-

Harvey Fineberg

-

Sherry Lansing, John Edward Porter

-

Craig Thompson, Jordan Gutterman, James Fordyce

-

Joseph Goldstein

-

Sandra Blackwood, Timothy Callahan

-

Francis Collins, Mrs. William McCormick Blair

-

Purnell Choppin, Joan Choppin, Martin Tolchin, Joe Perpich, Cathy Sulzberger

-

Mark Hochberg, Faith Hochberg

-

Bruce Stillman, Cori Bargmann

-

Amanda Young, Mary-Jeanne Kreek, John Gallin

-

Gerald Weissmann, Marston Linehan, Maria Freire

-

Hugo Marx, Susan Lasker Brody, Sherry Kidd

-

Maria Leonor Beleza, Christopher Brody

-

Visko Hatfield, John Gallin, Francis Collins

-

Tu Youyou interviewed by Lu-qi Huang

-

Tu Youyou interviewed by Lu-qi Huang

-

Participants in a pre-ceremony discussion on careers in biomedical research

-

Mike Overlock, Jill Sommer, Katharine Overlock

-

Mike Overlock, Jill Sommer, Katharine Overlock

-

Craig Thompson, Barbara Brody

-

Mary Wilson, Susan Okie, Larry Altman