Richard Scheller

Thomas Südhof

Graeme Clark

Ingeborg Hochmair

Blake Wilson

Bill Gates

Melinda Gates

The Art of Science

Opening remarks by Joseph Goldstein

An expanded version of these remarks originally appeared in Nature Medicine.

Juxtapositions in Trafalgar Square: Tip-offs to creativity in art and science

One of the delights and highlights of a trip to London is a visit to Trafalgar Square, the city’s premier public space. For the past 175 years, Trafalgar Square has been England’s favorite site for political rallies and national celebrations. It is also the home of the National Gallery, one of the premier art museums in the world. In the last few years, Trafalgar Square has taken on a new venture: it has become the site of a living laboratory of discovery where as many as 40,000 tourists each day can experience firsthand what creativity and innovation are all about. Before telling you about this exciting new development, let me briefly review the history and architectural layout of Trafalgar Square.

One of the delights and highlights of a trip to London is a visit to Trafalgar Square, the city’s premier public space. For the past 175 years, Trafalgar Square has been England’s favorite site for political rallies and national celebrations. It is also the home of the National Gallery, one of the premier art museums in the world. In the last few years, Trafalgar Square has taken on a new venture: it has become the site of a living laboratory of discovery where as many as 40,000 tourists each day can experience firsthand what creativity and innovation are all about. Before telling you about this exciting new development, let me briefly review the history and architectural layout of Trafalgar Square.

Figure 1. The Fourth Plinth of Trafalgar Square. This imposing slab of stone, erected in 1841, remained bare until recently. Beginning in 1999, the City of London began a rotating program in which different contemporary sculptures are selected to adorn the bare Fourth Plinth; each sculpture is exhibited for a 1.5- to 2-year period. Photo by James O’Jenkins (Institute of Contemporary Arts, London).

Adorning the bare Fourth Plinth with contemporary sculptures

Then, in 1999, a remarkable thing happened. The Royal Society of Arts came up with a bold way to solve the asymmetry problem: install on top of the Fourth Plinth a large contemporary sculpture that would infuse new life into the 175-year old Trafalgar Square (1). Like our own mayor of New York City, the last two mayors of London, Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson, are feisty, peppy, and popular. With great enthusiasm, they embraced the Fourth Plinth idea and authorized a commission to hold a competition every several years in which about 100 artists from around the world are invited to make a proposal. The winning artist is selected on the basis of two criteria: (i) does he or she view Trafalgar Square through fresh eyes that encapsulate the collision of Trafalgar’s two centuries of military heritage with the cutting edge of contemporary art; and (ii) will the artist’s proposed sculpture provoke the imagination of the 40,000 tourists who visit Trafalgar Square each day?

In the last eight years, six sculptures have adorned the Fourth Plinth in a rolling program. I will tell you about my two favorites and the artists who produced them: Marc Quinn and Katharina Fritsch. Their work exemplifies the type of exceptional creativity that wins Lasker Awards and Nobel Prizes.

Marc Quinn’s juxtaposition: Female nudity and male heroism

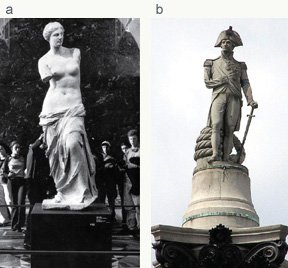

Figure 2. Juxtaposition that inspired Marc Quinn’s Fourth Plinth sculpture. (a) Alexander of Antioch (Hellenistic Age), Venus di Milo. ~100 BC. Marble. Height, 6ft 8in. Louvre Museum, Paris. (b) Edward Hodges Baily, Nelson’s Statue. 1843. Sandstone. Height, 18ft 1in. Trafalgar Square, London. Both arms of Venus di Milo were lost following discovery of the fragmented sculpture in 1820 on the island of Milos. The left arm of Lord Nelson was lost in battle.

Marc Quinn, one of the original so-called Young British Artists of the late 1980s, who is still brimming with bright ideas at age 50, conceived his sculpture from an insight originating from two unconnected ideas: (i) people who go to museums gravitate to fragmented nude statuary, such as the armless Venus de Milo, who is admired as a great icon of feminine beauty (Fig. 2); and (ii) people who go to Trafalgar Square view Lord Nelson, who lost one arm in battle, not as a disabled person, but as a great icon of military heroism (1). Juxtaposing these two disparate insights, Quinn produced a sculpture of a nude, heavily pregnant woman who was born without arms and with shortened legs caused by a condition called phocomelia. The model for the sculpture is a critically acclaimed British artist, named Allison Lapper, who does not use artificial limbs; she paints with her mouth. Lapper’s paintings have been exhibited widely in the UK and throughout the world. In 2003, she was awarded Membership in the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for her services to the arts.

Quinn’s sculpture, entitled Allison Lapper Pregnant, is carved out of a single block of Carrara marble, stands 12 feet high, and weighs 13 tons (Fig. 3). The sculpture is arresting and beautiful, yet at the same time strange and contentious — much like Velasquez’s dwarfs and Picasso’s eroticized biomorphic figures. The Allison Lapper piece stands in striking contrast to all the other monuments in Trafalgar Square, which commemorate dead, male military heroes and events of the past. The pregnant Allison Lapper celebrates events of the future and advances a new structural model for female heroism and humanity. During the two years that Allison Lapper and Lord Nelson rubbed shoulders in Trafalgar Square, Quinn’s sculpture — not surprisingly — elicited diverse reactions. Yet, during its time on display, it was the most popular tourist attraction and most widely discussed event in London — a wonderful affirmation of Mark Quinn’s creativity and innovation.

Figure 3. Marc Quinn, Allison Lapper Pregnant. 2005. Height, 12 ft. Exhibited on top of Fourth Plinth at Trafalgar Square, London, 2005-07. For additional information, see Rogers, R., Quinn, M., and Mack, M. Fourth Plinth. Steidl, Göettingen, 2008.

Katharina Fritsch’s juxtaposition: British heroes and French mascots

On July 20th of this year, a giant blue bird landed on the Fourth Plinth and will remain there until January 2015 (Fig. 4). This 15-foot-tall rooster, provocatively entitled Cock (Rooster), is made from fiberglass coated with polyester resin and painted in deep royal blue. It was designed by one of Germany’s leading artists, Katharina Fritsch, who is famous for creating oversized sculptures in a single beaming color, such as yellow Madonnas, green elephants, pink apples, and men in purple suits.

The creative spark that fired Fritsch’s imagination may have arisen from two unconnected ideas: (i) the rooster is an iconic symbol of male preening and posturing, and its presence in Trafalgar Square would be appropriate company for the likes of Lord Nelson, George IV, and the two Victorian generals; and (ii) the rooster is also the national symbol of France, serving as a mascot for sporting events such as soccer and rugby. Juxtaposing these two disparate insights, Fritsch came up with a sculptural installation that teems with humor and irony: a French rooster, created by a German artist, invades England’s most sacred military ground that celebrates her greatest naval victory over the French. Napoleon would not be amused!

Figure 4. Katharina Fritsch, Cock (Rooster). 2013. Fiberglass coated with polyester resin. Height, 15 ft. Exhibited on top of Fourth Plinth at Trafalgar Square, London, 2013-15. Photo by Andy Rain (The Telegraph).

Marc Quinn’s Allison Lapper may have rubbed shoulders with Lord Nelson, but Katharina Fritsch’s Rooster will surely ruffle the Admiral’s feathers. Fritsch’s blue bird is destined to be the talking point among Londoners and tourists for the next 15 months, waving his tail-feathers at the National Gallery and aiming his beak straight at Nelson’s back.

Francois Jacob’s juxtaposition: Enzyme induction and lysogeny

Like breakthroughs in art exemplified by the likes of Quinn and Fritsch, breakthroughs in biomedical research also arise by perceiving and connecting disparate ideas. One of the most famous examples involves the work of the brilliant French geneticist, Francois Jacob, who discovered in the early 1960s how genes are turned on and off. Jacob’s insight came in a flash while watching a movie in a Paris cinema. When he closed his eyes to shut out a boring scene, he suddenly realized that two types of research going on at The Pasteur Institute that were thought to be miles apart mechanistically were in fact two aspects of the same phenomenon. Jacques Monod’s work on induced synthesis of enzymes and André Lwoff’s work on phage lambda and lysogeny could both be explained by a single theory involving repressors that inhibit gene activity.

Francois Jacob died earlier this year at age 92. As pointed out in multiple obituaries, there were two keys to his creativity (2, 3). The first was his high style in designing experiments in which an absolute minimum of data produced a maximum of insight — an approach that is diametrically opposite to much of the way big science is done today. The second key to Jacob’s creativity was his masterful ability to see juxtapositions and analogies where others saw only separate phenomena.

Arthur Koestler’s theory of creativity

The concept that new ideas arise by the generation and juxtaposition of random combinations was first authoritatively examined by the Hungarian-British writer Arthur Koestler in his classic 1964 book, entitled The Act of Creation: A Study in the Conscious and Unconscious Processes in Humor, Scientific Discovery, and Art (4). According to Koestler, the creative activities of scientists and artists are closely related to those of comedians. The hallmark of a good comedian is one who thinks the unthinkable — not by thinking outside the box, but by mentally uniting several boxes of unconnected thoughts to create a totally novel thought, which becomes the punchline of a good joke.

Koestler chose to illustrate his point by analyzing a joke popularized by Sigmund Freud in his essay on wit:

The Marquis finds his wife in bed with a Bishop. He doesn’t say a word, but goes to the window and blesses the people walking under it. When his wife asks him what he thinks he is doing, he replies, “He is performing my function; I will perform his.”

This joke juxtaposes two normally dissimilar contexts, marital honor and the division of labor. This unexpected union produces an intellectual innovation — a eureka moment, which is the essence of any creative action, whether it be a good joke, a scientific discovery like Jacob’s repressor theory, or a memorable piece of art like Quinn’s Allison Lapper or Fritsch’s Rooster.

In the past 50 years, thousands of books and articles have been written on the subject of innovation and creativity, virtually all of which deal directly or indirectly with Koestler’s original ideas on the combinatorial nature of creativity. Two well-known examples of his influence are echoed in Jacob Bronowski’s famous quote, “The creative mind is a mind that looks for unexpected likenesses,” and in Steve Jobs’s dictum, “Creativity is just connecting the dots.”

Even though we have a general idea of how the juxtaposition of disparate ideas produces creative art and creative science, how the brain generates these juxtapositions at the biological and psychological levels is a great mystery waiting to be solved — the Grand Challenge of Creativity.

The last word on any discussion on creativity belongs to arguably the two most creative individuals of the past 100 years, Albert Einstein and Pablo Picasso. Both were asked by journalists, “What is creativity?” Einstein’s response: “The secret to creativity is knowing how to hide your sources.” Picasso’s response: “I don’t know, and if I did I wouldn’t tell you.”

References

Rogers, R., Quinn, M., and Mack, M. Fourth Plinth. Steidl, Göettingen, 2008. 48 pp.

Beckwith, J. and Yaniv, M (2013). François Jacob (1920-2013). Curr. Biol. 23, R422-R425.

Ptashne, M (2013). Francois Jacob (1920-2013). Cell. 153, 1180-1182.

Koestler, A. The Art of Creation: A Study in the Conscious and Unconscious Processes of Humor, Scientific Discovery, and Art. Macmillan, London. 1964. 751 pp.

Medical Research Awards Jury

2013 Lasker Medical Research Awards Jury

First Row, left to right: Charles Sawyers, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center ● Jeremy Nathans, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine ● Tom Maniatis, Columbia University ● Joseph Goldstein, Chair of the Jury, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center ● Diane Mathis, Harvard University ● Donald Ganem, Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research ● Robert Horvitz, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Second Row, left to right: J. Michael Bishop, University of California, San Francisco ● Stanley Cohen, Stanford University ● Eric Kandel, Columbia University ● Titia de Lange, The Rockefeller University ● Michael Brown, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center ● Gregory Petsko, Brandeis University ● Paul Nurse, The Royal Society

Third Row, left to right: Jack Dixon, Howard Hughes Medical Institute ● Marc Tessier-Lavigne, The Rockefeller University ● Richard Lifton, Yale University ● Craig Thompson, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center ● James Rothman, Yale University ● Cornelia Bargmann, The Rockefeller University ● Martin Raff, University College London

Not pictured: Roderick MacKinnon, Rockefeller University

Public Service Award Jury

Ambassador Barbara Barrett ● Susan Desmond-Hellmann, University of California, San Francisco ● W. J. Overlock, Jr., 3G Capital ● Alfred Sommer, Chair of the Jury, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health ● Robert Tjian, Howard Hughes Medical Institute ● Elias Zerhouni, Sanofi

Ceremony

-

Claire Pomeroy, Thomas Südhof, Richard Scheller, Alfred Sommer

-

Graeme Clark and Kailan Sierra Davidson discuss cochlear implants at the Lasker Scholars' Breakfast

-

Blake Wilson, Ingeborg Hochmair, and Graeme Clark

-

Medical Research Award Jury Chair Joseph Goldstein speaks about scientific and artistic creativity

-

Joseph Goldstein, Thomas Südhof, Claire Pomeroy, Richard Scheller, and Alfred Sommer

-

Melinda and Bill Gates

-

Claire Pomeroy, Bill Gates, Michael Bloomberg, Melinda Gates, and Alfred Sommer

-

Alfred Sommer and Bill Gates, Sr.

-

Yulian Zhou, Rebecca Gorla, and Mandy Wong

-

Ingeborg Hochmair's award acceptance speech

-

Ingeborg Hochmair and family

-

Melinda Gates, Alfred Sommer, Bill Gates

-

Jordan Gutterman (center) leads a panel discussion on art and science

-

Eric Kandel delivers an overview of regulated neurotransmitter release

-

Richard Scheller (center) speaks about careers in science at the Scholars' Breakfast

-

Blake Wilson at the Scholars' Breakfast

-

Max R. (center), the world's first recipient of bilateral cochlear implants

-

Mayor Michael Bloomberg

-

Joseph Goldstein and Melinda Gates