Great technological advances of recent decades have enormously facilitated the earlier recognition of disease. With the progressive aging of our population, early recognition of the inevitable neoplastic and degenerative disease of middle age becomes an increasingly important part of preventive medicine. The handicaps to accomplishment are again largely economic. Cost as well as ignorance prevent the early utilization by the masses of people of the newer medical techniques for detecting the first manifestations of disease, when it can be more readily cured or arrested.

There is no longer any dispute among physicians that the financial handicaps of everyday life prevent the fullest application of scientific discoveries to disease prevention and that this barrier can only be removed by prepayment for comprehensive medical care. The only remaining difference of opinion relates to the manner in which this can best be accomplished. The debate has narrowed down to two alternatives: (1) immediate nationwide adoption of a compulsory system of medical insurance, or (2) gradual experimentation in local areas in order to determine the changes in the methods of rendering medical services which may be required under a voluntary or compulsory prepayment plan.

I favor the latter alternative. But this is not the occasion to renew these discussions, important though they may be. It is apparent, I hope, that preventive medicine cannot at this time, if ever, be left wholly to the much preoccupied medical profession. It is equally the responsibility of the public health profession whose concern with the reduction of morbidity and mortality is not handicapped to the same extent by the personal and financial impediments which divert the medical profession from assuming its full share of the task.

These were the considerations, I have no doubt, which persuaded the donors of the Albert and Mary Lasker Awards for Scientific and Administrative Achievement to make their generous gift to the American Public Health Association, rather than to some purely medical organization of national scope. In endowing these awards, it was not the sole purpose of the donors to reward scientists and administrators for their outstanding contributions to medicine and pubic health, for such men need no incentive. Rather, it was their intention through these annual awards to bring the most important achievements in the medical sciences as early and as conspicuously as possible to the attention of the entire public health profession and to the people of this country, in order to encourage earlier and wider utilization of new knowledge and reduce the lag which too frequently intervenes between scientific discoveries and their application to the control of disease. With this in mind, the donors indicated their wish that the scientific awards be made for discoveries related to those diseases which are among the commonest causes of morbidity and mortality.

With the help of many Fellows and members of this Association, your Awards Committee, consisting of representative medical scientists and public health experts from various sections of the country, has reviewed a great mass of data bearing upon the most outstanding scientific and administrative achievements of recent years. Although you may be surprised at some conspicuous omissions, I can assure you that the Awards Committee has carefully considered all the facts and that the selections which are about to be announced were unanimous.

The reading of the citations I shall entrust to Dr. Abel Wolman. A brief comment may be appropriate at this time concerning the details of the scientific investigations and administrative achievements which were selected by the Awards Committee, and their significance for public health.

The discovery of Rh factor and its significance by Dr. Karl Landsteiner (deceased) who previously won the Nobel Prize, and his collaborators Drs. Alexander Wiener and Philip Levine, occurred as long ago as 1937. However, a true appreciation of its important role in the cause and prevention of material and neonatal morbidity and mortality and in transfusion accidents has grown rapidly only in recent years. For this reason, perhaps, it has never received public recognition through an award, in spite of its increasing public health significance. The absence of Rh factor in the blood of the mother and its hereditary presence in the unborn child may result in miscarriage, or, especially in later pregnancies, in fatal diseases of the newborn infant. Certain blood disorders and fatal jaundice of the newborn, and even some congenital monstrosities are now known to be due to this factor. Even the mother’s life is in jeopardy, for an Rh-negative mother can become sensitized, after repeated pregnancies, to the Rh-positive factor in the blood of her unborn children, and may then be killed by a transfusion with blood from an Rh-positive donor. There can be no dispute that knowledge of the importance of Rh factor and means for its utilization for the protection of mothers and of newborn babies should be available to all public health workers. There are even some who regard this matter as so important that they now advocate the amendment of state public health laws so as to make the test for Rh factor, like the prenatal test for syphilis, compulsory for all pregnant women.

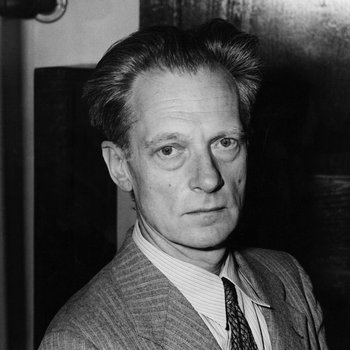

The discovery by Dr. John F. Mahoney of the rapid curative effect of penicillin in early syphilis, a cure after eight days of treatment, now makes it possible to control this widespread disease which during this postwar period might otherwise reach epidemic proportions. The treatment is safe, for it has none of the toxic effects of the rapid treatment with arsenic. The rapidity and completeness of syphilis control by means of this new cure will now depend upon the resources and the effectiveness of public health authorities in discovering the original contacts under treatment before the victims can expose themselves to immediate re-infection. Because of this increased danger of prompt re-infection, the discovery of a rapid cure, I venture to predict, will still be ineffective in reducing the frequency of the disease in the populace unless public health workers understand the importance of the role which they are called upon to play and of the speed with which they must now work in discovering and treating all the contacts. For this reason, the utilization of Dr. Mahoney’s discovery for the eradication of syphilis must be accepted as the responsibility of public health departments rather than of the medical profession.

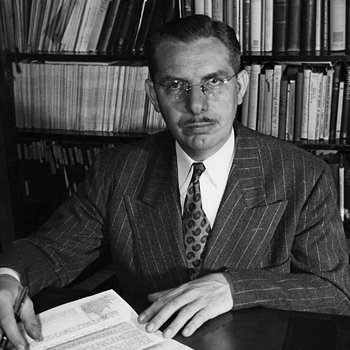

The discovery by Dr. Carl Ferdinand Cori of a new fundamental principle which governs carbohydrate metabolism may seem, at first thought, to be far removed from the field of public health. Yet, this work is revolutionary, for it throws an entirely new light upon the manner in which sugar is burned in the body as fuel and upon still another mechanism through which some of it is converted into a substance resembling starch (glycogen) and stored in the liver for future use. Dr. Cori’s work also demonstrates the indirect role played by insulin upon the important enzymes or ferments which govern the metabolism of sugar within the cells of the body. His discovery teaches us why insulin is only palliative and not a cure for diabetes. It provides a new understanding of the nature of the disturbed mechanism which we call diabetes, a disease affecting more than a million inhabitants of our country. Although the prevention of diabetes is not as yet possible, new insight into its cause has now been gained, upon which future progress in prevention and cure must eventually be predicated.

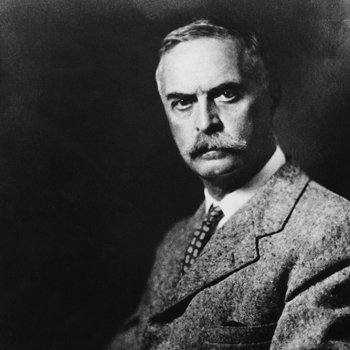

Two awards were recommended by the Committee for outstanding administrative achievements in science. One was the organization and administration during the period of the war of the Committee on Medical Research of the Office of Scientific Research and Development. During the war, research in the field of the medical sciences in medical and other laboratories throughout the country was carried out under contract with this Committee, and under the supervision of its Director, Dr. Alfred Newton Richards. This included the mass production of penicillin in time to help save the lives of hundreds of thousands of our troops on the battlefronts, the search for a better antimalarial drug than quinine to prevent and cure malaria, the development of efficient insecticides and insect repellents for the fight against the louse which transmits typhus fever and the mosquito which transmits malaria, the creation of new techniques for the preparation of plasma and whole blood transfusion, and hundreds of other important research projects. In the opinion of the Awards Committee, the work of the Committee on Medical Research, under Dr. Richard’s leadership, constituted one of the greatest accomplishments in nationwide coordination and administration of organized medical research which this or any country has ever witnessed.

A second award for outstanding administrative achievement was made to Dr. Fred Soper for the effective utilization of the principle of species eradication of insect vectors. Although his work on the elimination of the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae, was first undertaken in 1936, it continues to be carried on in various parts of the world with increasing effectiveness and holds promise for the control of yellow fever, malaria and certain other tropical diseases, a great achievement which may help to make the tropical areas of the globe habitable for mankind. The importance of this work is further illustrated by the fact that there are more than 300 million cases of malarial fever throughout the world each year, and at least three million malarial deaths.

Each of the distinguished scientists responsible for the five outstanding scientific achievements which I have just enumerated is to receive an award of $1000 and a gold statuette, a replica of Winged Victory, on the base of which an appropriate citation is inscribed.

During the deliberations of the Awards Committee, it became evident that other outstanding scientific advances in medicine and public health were made during the war by groups of hundreds of men and women, military and civilian, working together against time to solve a specific problem of great importance to the health of the military forces and of the civilian population. For this reason, the Committee decided to add five group awards this year in addition to the originally planned individual awards. These group awards are in the form of a citation and a Winged Victory statuette in silver which will be presented to the administrative leader of each group. They will go to the US Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine for its work on insect control, to the Northern Regional Research Laboratory of the Department of Agriculture for the mass production of penicillin, to the Board for the Coordination of Malarial Studies for the development of new drugs for the prevention and cure of malaria, to the Army Epidemiological Board for the control of infectious disease in wartime and, more particularly, for the development of an effective vaccine against influenza, and to the National Institute of Health of the United States Public Health Service for its notable work in the field of nutrition and in the development and production of vaccines against Rocky Mountain spotted fever, typhus and yellow fever, and for a great volume of other scientific research of importance in war and in peace.

I would urge the members of the Association to familiarize themselves with the details of the important research projects for which these awards are being made. They are among the most important contributions made by medical science in recent years to the advancement of public health. They are expected to have a far-reaching influence upon the control of the diseases which are among the chief causes of morbidity and mortality. The American Public Health Association and the people of this country are indeed deeply indebted to the wise and generous donors of the awards, the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation.

Before describing to you some recent advances in the medical sciences which your Committee on Science Awards considers important to public health, I should like to pay a tribute of appreciation to the donors of the Albert and Mary Lasker Awards for outstanding scientific and administrative achievements. I especially applaud their wisdom in entrusting to the American Public Health Association the selection of the recipients of these awards. It indicates their understanding of the fact that the prompt utilization of scientific medical discovery for the prevention of disease is the function of the public health profession, as much as it is the function of the profession of medicine.

Before describing to you some recent advances in the medical sciences which your Committee on Science Awards considers important to public health, I should like to pay a tribute of appreciation to the donors of the Albert and Mary Lasker Awards for outstanding scientific and administrative achievements. I especially applaud their wisdom in entrusting to the American Public Health Association the selection of the recipients of these awards. It indicates their understanding of the fact that the prompt utilization of scientific medical discovery for the prevention of disease is the function of the public health profession, as much as it is the function of the profession of medicine.